Most Southern families have their tales of Princess We-no-not-who. Typically, she was Cherokee. Sometimes Choctaw or Creek. Rarely Chickasaw or Seminole. Traditionally, the tale was a whispered one, something to regale the children but not for public knowledge—at least not until the 1970s when a shift in social ideals made minority ancestry both chic and profitable.

Proving that tale is far harder than believing it. Still, whether one is a family historian or an academic, that burden of proof exists. Ancestors are not merely leaves on a tree, to be colored however we please. Each was a human being who lived a unique life—someone who suffered or prospered, toiled and dreamed in his or her own way. Their names may be interchangeable but their lives are not. Thomas Jones and Thomas Carpenter Jones make that point.

CASE AT POINT: THOMAS & ELIZABETH JONES

In 1950, the Texas-born Elizabeth (Williams) Meharg sat down and penned a memorandum about her family, in which she reported:

“My Grandmother Williams’ father was still living at 108 years old but was still active. He was a Revolutionary War Veteran. His wife was half Indian. We have always been proud of our Indian blood. . . .”1

So goes the typical family tale: service to the American cause, super-longevity, and a half-Indian wife. Tales of full-Native wives were, by the unwritten code of that era, a bit unseemly.

Mrs. Meharg also identified the centenarian of lore as Thomas Carpenter Jones. His “half-Indian” wife was “Mollie.” By 1984, her descendants had unearthed evidence to support their tale: a few records from well-known collections at the National Archives, some published items from library shelves, and a smattering of things from no-one-was-quite-sure-where. All together, they put flesh on the bones of the family tale and staked its claim to Cherokeehood. Chief among these records (no pun intended) were these:

- The Revolutionary War pension application of “Thomas C. Jones” of Blount County, Alabama, reported his birth in Edgefield, South Carolina, on 19 June 1765. According to Jones’s affidavit, he served several short stints through 1783. Migrating out to the frontiers of Kentucky and Tennessee, he spent a year among the Cherokee, “under their permit,” before settling in Blount County. There, in 1829, he took a new wife, Margaret Nesbit, who survived him at his death on 5 February 1856.2 By his own reckoning, he was 91 at death, quite a few years short of the vaunted 108.

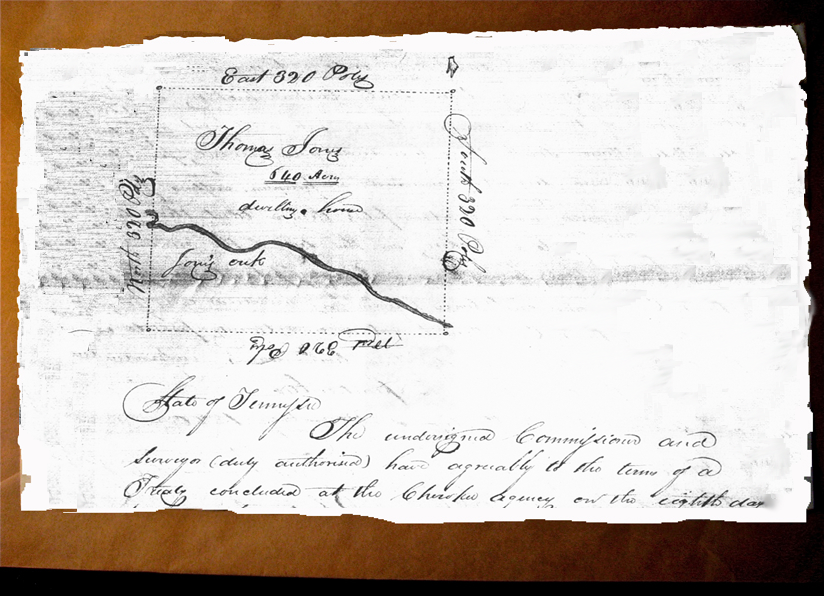

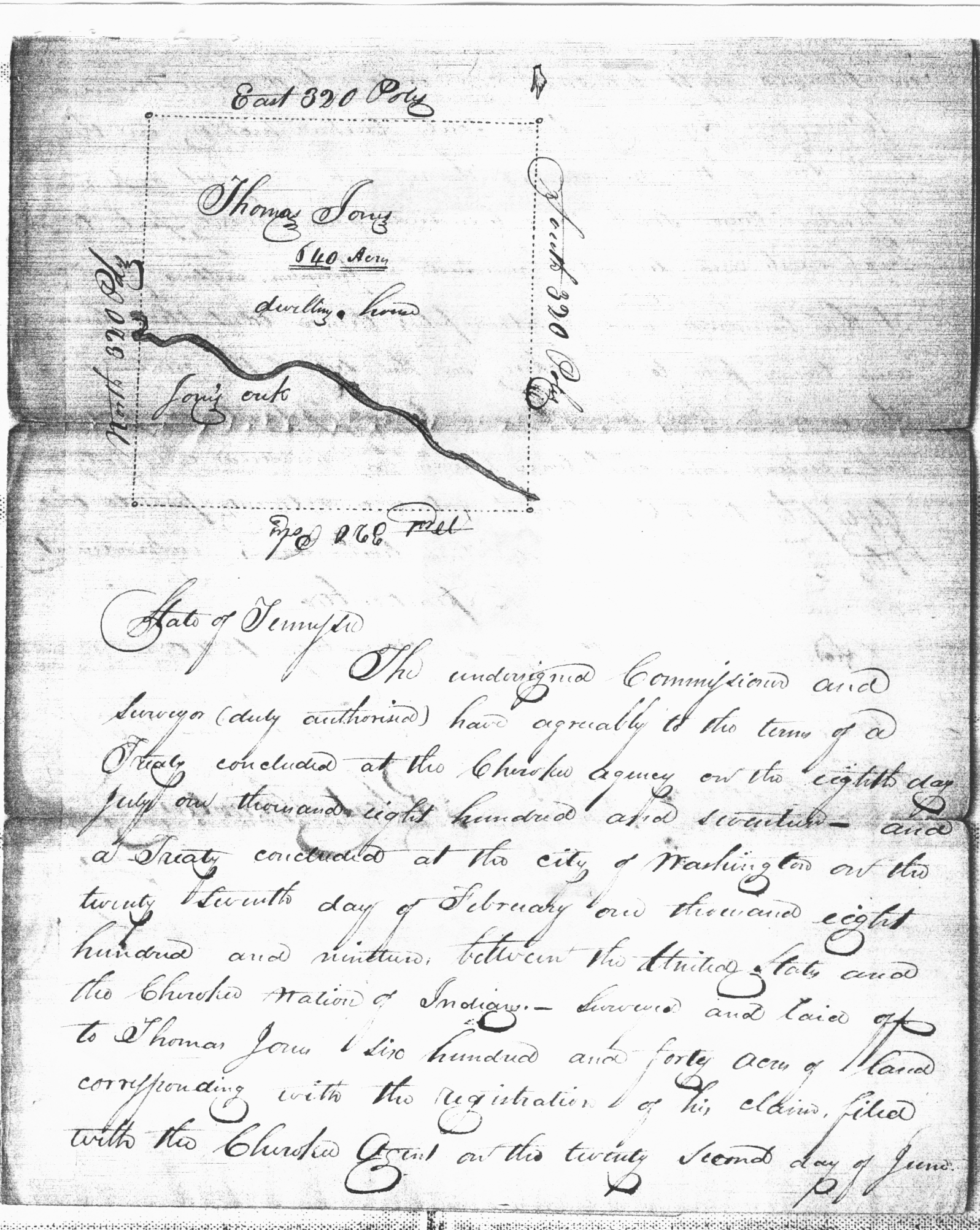

- U. S. land survey plats of November 1820 documented four 640-acre Cherokee reservations in the names of “Thomas Jones, James Jones, William Jones, and Drury Jones.” They also named a Thomas Jones Junr., who served as chain carrier for the surveys. The Jones tracts were said to lie along Jones Creek, in an unnamed county and state, and were laid out by the Tennessee-based surveyor “agreeably to the terms of a Treaty Concluded at the Cherokee Agency” on 8 July 1817.3 From these, family researchers deduced that the four additional males were undoubtedly the children of Thomas Carpenter Jones and the “half-Indian Mollie.”

- A published act of the Alabama Legislature, passed 31 December 1823, decreed “That Thomas C. Jones be restored to all the rights and privileges of citizenship in this state ... as though he had never forfeited the same.” The act did not specify why, when, where, or how Jones had forfeited his citizenship—or, for that matter, where in the state of Alabama this man lived.4

- An affidavit of 7 April 1831, filed in Alabama’s Jackson County, asserted that “Thomas Jones Junr., Elizabeth Jones, David Jones, James Jones, John Jones, and Drury Jones” had sold their land (no date cited) to one William D. Gains—land described as the Thomas Jones Reservation on Jones’s Creek, Jackson County.5

- U.S. Land Office patents dated 26 July 1819 and 20 June 1836, confirmed purchases by “Thomas Carpenter Jones”of two tracts in Blount County.6 That land marked the site where census enumerators of 1840 and 1850 found the elderly Jones, his wife Margaret Niblet, and his presumed sons Thomas Jr. and John.7

Five sets of records, all original materials, seemed to create a compatible story line. Thus, the tale was “proved” in the eyes of those who wanted to believe. Yet the devil always lurks in the details. In this case, those details raised pesky questions in at least two areas:

Why did Thomas C. Jones of 1823 have his Alabama citizenship restored? What did he do to lose that citizenship? Exactly which of Alabama’s Thomas C. Joneses was he?

The family’s assumption that this man lost his American citizenship by marrying a Cherokee wife was easily rebutted. Neither the U.S. nor the State of Alabama had any such law stripping citizenship from the thousands of “countrymen” who took Native wives.8

How did the six Joneses of 1831 acquire the Jones Creek reservation originally granted to Thomas Jones?

A family supposition that the six were children and heirs of the reservee was a difficult fit for known facts about Thomas Carpenter Jones.9 Yet, in circumstances of this ilk, “facts” can be easily stretched to cover wishes. The proved fact that the three documented children of Thomas of Blount were not named in the Jackson County affidavit was perceived as evidence that the old man had two families. Obviously, the Indian wife “Mollie” bore the first set of children. After her death, the new wife produced another.10

An even more inconvenient fact—the patriot Thomas lived another quarter-century after the Jackson County sale by his presumed heirs—was similarly “resolved.” Obviously, Thomas Carpenter Jones had settled inheritance matters between his two families by letting the first set of children have his Jackson County reserve, while leaving the Blount County land to his second family. Again a troublesome detail pricked at this argument: Thomas Carpenter Jones’s will named one son by his first wife (a wife he actually cited as Mollie) but that son, Solomon, was not an heir to the Jackson County reserve.11

Family-history’s Standards

Finding random documents to support what we want to believe is not research. It’s self-delusion. Family tales, beloved or otherwise, carry no credibility unless they meet common standards for family history research—the first of which is reasonably exhaustive research.12

Meeting this genealogical standard meant the use of all known and discoverable records for the appropriate places, events, and time frame. Jackson County’s courthouse has suffered several fires and newspapers are in short supply for that frontier, but other records abound:13

- Both Jackson and Blount offered deeds and tract books (but no tax records), probate files, court cases, local merchant accounts and even church minutes. None hinted at a Cherokee link for Thomas Carpenter Jones.

- State legislative records yielded no trace of Thomas C. Jones’s petition to have his citizenship restored, wherein he should have explained how or why he lost his citizenship.14 They did, however, reveal a similar “relief act” for one William Jones of nearby Walker County, vaguely said to be a “remote descendant of a tribe of Indians.”15

- Federal land records yielded credit sales, cash sales, and military bounty land files that also conflicted with the family’s premature conclusions—pesky conflicts of the type no credible family history can ignore.

- Files of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and its predecessor, the War Department, had far more to offer than the 1820 surveys along Jones Creek. Indeed, they were a treasure trove.

As with most family lore the reality revealed by more-thorough research tells a far more meaningful story than the sketchy family tale.

Reality

In 1817, the United States and the Cherokee Nation signed the first treaty by which Southeastern Native Americans were persuaded to move west of the Mississippi. As with many such treaties, individual tribal members and white countrymen with Native families were given the option of staying behind on a tract of land allotted to them as individuals.16 One Thomas Jones and his three young-adult sons, William, James, and Drury, declared their wish to stay and were among those deemed “persons of industry and capable of managing their property with discretion.17 In 1819, the year that Thomas Carpenter Jones took out his first land in Blount, the Cherokee Joneses were assigned the lands on which they had already settled—along Jones’s Creek of what had just became Jackson County.18

Soon, a horde of American settlers flooded into the newly ceded lands around the Joneses. Not surprisingly, they included a few bad actors unwilling to accept any Native Americans as their neighbors. The fact that Thomas Jones was white, that his wife Elizabeth (not “Mollie”) was only one-quarter Cherokee, and that their children were but one-eighth Native earned them no consideration.19

By 1830, the Cherokee Joneses had removed to Western Arkansas, the first Indian Territory. The protracted legal claims they waged against the U.S. over the next fifteen years tell their heart-wrenching story. In the words of the eldest son Drury:20

“First Day of April 1845

“The reservation entered by my father Thomas Jones for my mother Elizabeth was in Jackson County. My father was a white man and my mother a native Cherokee—my mother and her family had been living in the place [of] the reservation between three and four years before the treaty of 1817. ... My mother had seven children at the time of the Treaty—five of them lived with her, the other two, James Jones and myself, were both married ... and settled to ourselves. ...

“Several years after the treaty ... several white men ... were in the habit of coming to Mother’s house and tormenting her in every way they could devise. They invariably appeared at night and would stone the house, in some instances broke in the doors and windows with heavy rocks. One time ... a stone was thrown which struck my father upon the face and broke his jawbone. At another time they threw the grindstone down the chimney.

“These attacks were very frequent, sometimes twice and three times a week and becoming more harassing. ... Father at last came to the conclusion that it was impossible for them to live upon the reservation and him and mother very reluctantly left it and removed into the Cherokee Nation across the river about five or six miles distant.21

“About two years after he left the reservation, father died, when absent from home in a visit to the Chickasaw Nation. My mother continued to reside upon that place until she emigrated to this country in the year 1831 or 1832 and died six years ago next August.” 22

Unfortunately for the family that prompted this study—the one so “proud of their Indian blood”—the tragic story was not theirs to claim, to rue, or to treasure. The Revolutionary War Indian fighter Thomas Carpenter Jones who settled Blount County in 1819 and survived there until 1856 was not Thomas Jones, Indian countryman, of Jones’s Creek in what became Jackson County. The two men had different children, different wives, and different lives. The only thing they had in common was their first and last names.

The Bottom Line

Ancestry is not a bowl of jelly beans from which we can pick and choose whatever flavor we crave. Each of us is the byproduct of specific ancestors whose DNA and life experiences are traceable threads from which our own being is woven.

Southern stories of Indianness sometime prove to be rooted in fact, but typically many generations earlier than lore contends.23 Even then, researchers soon learn two lessons: Name’s-the-same doesn’t mean the person is; and There’s no such thing as The Gospel According to Grandma. Those who cling to a belief in that gospel, as a rule, end up proving descent only from two modern American tribes: the Wannabes and the Outalucks.

1. Typescript provided 17 January 1984 by Virgil Meharg, son of Elizabeth Williams Meharg, to Elizabeth Shown Mills.

2. Thomas C. Jones (Pvt., Simkins’s Co. of Purvis’s Regt., and Powel’s Co. of Hammond’s Regt., S.C.; Sumrall’s Co. of Clarke’s Regt., Ga.; Rev. War), pension application no. 26160; digital images, Fold3 (http://www.fold3.com : last accessed 20 May 2012); imaged from Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives microfilm publication M804, roll number not cited but should be 1,446. Thomas C. Jones’s death date and the date of his marriage to Margaret appear in her widow’s affidavit of “[blank] day of August 1856,” filed in this same packet.

3. Surveys for Thomas Jones, Drury Jones, James Jones, and John Jones, made 28–29 November 1820, labeled “Plat and Certificate” nos.” 67–70, appear with the subsequent claims filed by Drury, James, and John. The various documents relating to these claims are scattered through several record series in National Archives Record Group 75, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs: especially, Applications for Reservations, 1819; Docket Book for Reservation Claims, 1837–39; Reservation Claim Papers, 1837–39; and Decisions on Reservation Claims, 1837–39; all these series are part of the subgroup “Cherokee Removal Records.” See also Index to Registers of Reserves; Register of Cases in Reserve File A; and Reserve File A, ca. 1825–1907; all part of the RG 75 subgroup “Records Concerning Indian Land Reserves: Records Relating to Claims.”

4. Acts Passed at the Fifth Annual Session of the General Assembly of the State of Alabama (Cahawba: Wm. B. Allen & Co., 1824), 109, “An Act for the Relief of Thomas C. Jones.”

5. Jackson Co., Ala., Deed Book D: 26, affidavit of William J. Price attesting sale of an interest in land by the Joneses to William D. Gains. The actual deed is not filed with the affidavit.

6. Final Certificate 90, Credit Under Files (Thomas C. Jones) for SW¼, Section 24, Township 12, Range 2 West, settling credit purchase made by Jones 26 July 1819 as assignee of William Dunn; also Cash Cert. Files, no. 9607 (Thomas Carpenter Jones) for SW¼ SW¼ S12 T12 R2W, and no. 9608 (Thomas Carpenter Jones) for NE¼ NW¼, S13 T12 R2; both dated 20 June 1836. All are identified as Blount County lands; all papers are from the Huntsville, Alabama, Land Office Series, Records of the General Land Office, RG 49, National Archives.

7. 1840 U.S. cens., Blount Co., Ala., p. 15, line 26 (Thos. C. Jones, pensioner); 1850 U.S. cens., Blount Co., 17th subdivision, p. 163, dwelling 554, family 557 (Thos. C. & Margaret Jones). The 1830 U.S. cens., Blount Co., carries two inconclusive entries: one for a “Thomas Jones” of compatible age and family composition, and one for “Thomas C. Jones,” who was a decade younger with incompatible family composition (p. 21, line 23, and p. 23, line 1)..

8. This point is determined from a review of U.S. Congress, The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America, 1789–1873, 17 vols. (Washington, D.C.: [various publishers], 1845–73); and Harry A. Toulmin, A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama ... in Force at the End of the General Assembly ... 1823 (Cahawba: J. & J. Harper, 1823).

9. The six presumed heirs were subsequently proved to be the widow and children of the Indian countryman Thomas Jones, not the children of Thomas Carpenter Jones of Blount County. See for example, U.S. Congress, 22nd Cong., 1st sess. (1831), House Doc. 951, by which Congress approved William King’s petition for a title to Jones’s reservation. King stated that his father-in-law William D. Gaines had bought out the interests of “Jones’s children ... all of full age,” as well as the dower right of “the wife of Jones.”

10. Blount Co., Ala., Deed Book B: 257?, for Thomas C. Jones will, 20 May 1837; no will book was maintained in the county at that time. Although Jones created and filed that will in 1837, he did not die until 1856. The second wife and children named in the will all appear with him on the 1850 census (see n. 7 above).

11. Thomas’s 1837 will identifies his former wife as “Mollie” and names their adult son Solomon as his executor. Their other children are not named. Two putative sons of Thomas Carpenter Jones were adults by 1832 and 1836, when they obtained federal land close by Thomas C. in Blount County. See Cash Cert. Files, no. 5623 (Greenberry Jones), NW¼ SW¼ S26 T12 R2W, dated 22 October 1832, and no. 6962 (Saul Jones), NE¼ of SW¼ S24 T12 R2W, 6 January 1834; Huntsville, Alabama, Land Office Series, RG 49. The 1850 census reports Saul’s age as 50, Greenberry as 45; see 1850 U.S. cens., Blount Co., 17th Subd., p. 162, dwell. 537, fam. 540 (Saul) and p. 173, dwell. 685, fam. 689 (Greenberry).

12. Family-history standards are codified in Board for Certification of Genealogists, The BCG Standards Manual (Orem, Utah: Ancestry Publishing, for the Board, 2000), see pp. 1–2, particularly, for the five criteria of the Genealogical Proof Standard.

13. The dozens of relevant records found in these collections are far too numerous to cite or discuss. This QuickLesson focuses only on those most significant to the issue of Native heritage.

14. Mimi Jones, Head, Reference Division, Alabama Department of Archives and History, to Elizabeth Shown Mills, 11 September 1984 and 17 June 1985, reporting results of searches within the state legislative files.

15. Acts Passed at the Ninth Annual Session of the General Assembly of the State of Alabama (Tuscaloosa: Dugald M’Farlane, 1828), 127–28; adequate proof has not been found to connect this William Jones of Walker County to a birth family.

16. Charles J. Kappler, comp. and ed., Indian Affairs: Laws & Treaties, vol. 2,Treaties (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 140–44 (Treaty of 1817, particularly Art. 8), and 177–80 (Treaty of 1819, particularly Art. 3.

17. Art. 3 provides the quote. For the inclusion of the Joneses in Art. 8’s provision, see “List of Persons Entitled to Reservations of Land Under the Treaty with the Cherokee Indians of February 27, 1819,” Nos. 66–69 (Thomas, William, Drury, and James Jones), 20th Cong., 1st Sess. (1828), H. Doc. 615.

18. Surveys for Thomas Jones, Drury Jones, James Jones, and John Jones, made 28–29 November 1820, previously cited.

19. The percentage of Cherokee “blood” possessed by Thomas Jones’s children is stated in their previously cited claim files. For example, the 7 January 1830 affidavit in James Jones’s claim begins: “We certify that James Jones is one eighth Cherokee, about thirty years of age, and about five feet Ten inches high.” The certification for John Jones, carrying the same date, also states that he was one-eighth Cherokee, about 5’9” and 20 years of age.

20. Affidavit of Drury Jones, filed by David Jones, Adm., Claim of the Children and Heirs of Elizabeth Jones, 1 April 1845, file 105, Cherokee Improvement Claims; Special Files of the Office of Indian Affairs, 1807–1904, M574, roll 17; document extracted 3 January 2000 by Marsha Hoffman Rising for Elizabeth Shown Mills.

21. Under Art. 1 of the 1819 Treaty, the Cherokee ceded the last of its land in modern Alabama that lay north of the Tennessee River. A considerable tract of land south of the river remained in Cherokee possession until the Treaty of 1836, including a swath that divided Jackson County from Blount. For a very good depiction of the region, between these two treaties, see the 1820 and 1830 census maps created and published by William Thorndale and William Dollarhide, Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, loose map edition (Bellingham, Wash.: Dollarhide Systems, 1983) or bound edition (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1987). Walker County lay just west of Blount, considerably distant from Jackson.

22. Drury’s account of his father’s troubles and subsequent death is supported by the previously cited House Doc. 951, which reports a passage from William King’s petition for title to the land: “Jones lived on his said reservation till 1820 or 1821, when ... the white people who had settled around him ... threw down his houses, destroyed his fences, and so abused and maltreated him personally that he was compelled to abandon it.” King also asserted that after Jones sold his land to King’s father-in-law Gaines, “Gaines took Jones to live with him and treated him as a member of the family until he went on a visit to his friends and relations in the southern part of Alabama, where he was taken sick and died.” The claimed care of Jones by Gaines has not been proved. King did not report that at least one of the "abusers" was his own kinsmen—a fact revealed in Drury Jones's affidavit.

23. Proving that Native American connection will also, typically, be as complex as the case at hand—or more so.

How to cite this lesson:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 7: Family Lore and Indian Princesses,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-7-family-lore-and-indian-princesses : [access date]).