No. Historical records do not speak for themselves. They cannot explain themselves. They are inert objects created by individuals of a different time, a different culture, and who-knows-what mindset. If taken at face value, they can deceive, mislead, or confuse.

The only voice that documents have is the voice we give them—either through the context we provide or the passive acceptance with which we report them.

Every historical record we find needs to be interpreted at two levels:

- Each individual word must be understood—as it was defined and used when the document was created.

- The content of the entire document needs to be evaluated in the context of legal, social, religious, and political parameters.

As historical researchers who continually venture into new crannies of the past, we are often tempted to "let the records speak for themselves." We are often pressed for time to meet project deadlines. We may doubt our own understanding of a situation or a culture and feel that silence is the best service we can give to the issue. It isn't. Context matters. We should never speak without knowledge, but taking the time to understand the circumstances that created the document can radically change our view of what the document is telling us.

Case at Point:

On 17 February 1860, a free woman of color named Cora Bellanger filed a petition with the probate judge of Chambers County, Alabama. According to her words—supposedly they are her words—she was over 21 and had been living there in Chambers with Mrs. Elizabeth C. Witter, wife of Henry Witter. The reason for her petition? “Cora desires to become the slave of the said Elizabeth C. Witter ... because of the attachment and affection she has and bears to the said Elizabeth C. Witter.”1

What? A free woman desires to become a slave?

Recently in a closed online forum, a researcher commented about a group of similar petitions filed about that time in Mobile, Alabama, by which several of that city’s free people of color petitioned to be reenslaved.2 Those Mobilians felt, we’re told, that they would fare better under the benevolence of a kind master than fending for themselves in the free world.

Cora’s words—and those of her counterparts in Mobile—are very plainly written. Should we take them at face value? If not, why not?

Cora teaches us why context matters.

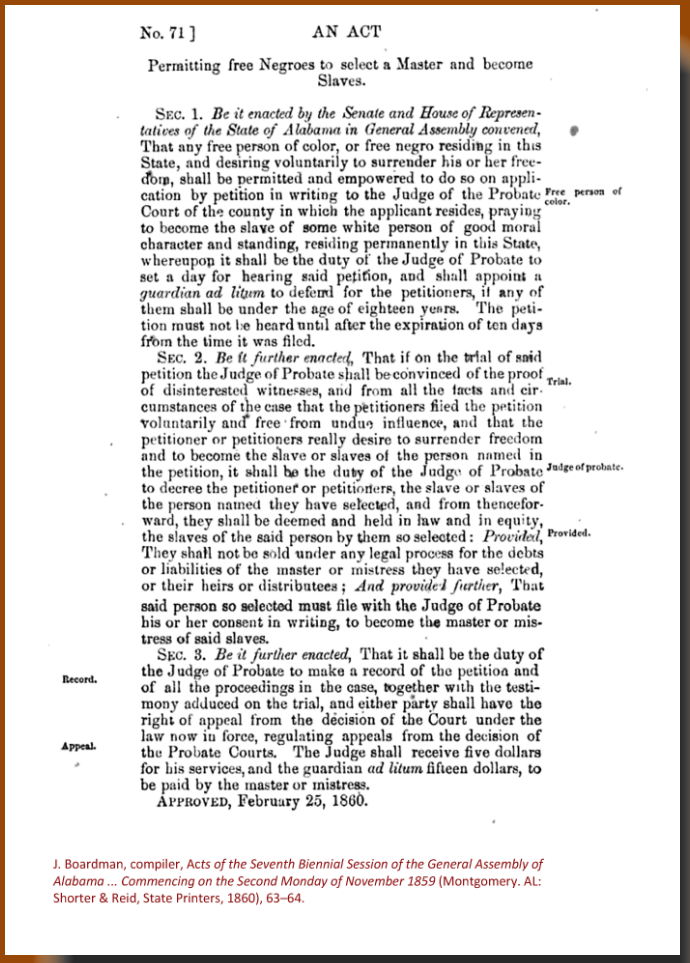

In that month of February, 1860, the Alabama legislature had before it a bill entitled “An Act Permitting Free Negroes to Select a Master and Become Slaves.” The act passed on 25 February. But in one county, Chambers, individuals who stayed abreast of politics were already filing petitions “on behalf” of domestic workers and farm laborers such as Cora. When passed, that bill decreed

“Any free person of color, or free negro residing in the State, and desiring voluntarily to surrender his or her freedom, shall be permitted and empowered to do so on application by petition in writing to the Judge of the Probate Court of the county in which the applicant resides, praying to become the slave of some white person of good moral character and standing, residing permanently in this state. ...

If on the trial of the said petition the Judge of Probate shall be convinced of the proof of distinterested witnesses, and from all the facts and circumstances ... that the petitioners filed the petition voluntarily and free from undue influence ... it shall be the duty of the Judge of Probate to decree the petitioner or petitioners, the slave or slaves of the person ... they have selected ... Provided, They shall not be sold under any legal process for the debts or liabilities of the master or mistress they have selected, or their heirs or distributees. ...3

Cora was not the only free person of color in Chambers County who reportedly felt they would be better off enslaved. Similar petitions would be filed in the names of at least fourteen others between 1861 and 1864. Others would be filed in Mobile—but have not been found elsewhere in the state. When the proposed masters presented witnesses, those witnesses consistently testified that they knew that man (or woman) “really desires to become a slave and filed this petition without undue influence, having said so in a private conversation.”4

How freely was that choice made? If we don’t take for granted the words that appear on that one document—if we search for these other free men, women, and children in the county's other surviving record sets—we see a far different situation from that implied by the words of the document that bears Cora's name.

Cora’s petition was, in fact, a watershed moment for free people of color in Chambers County. It marked a turning point on a slippery slope of restrictions placed upon the county's fpc since 1855—five years in which every free person of color had been required to select a white guardian to “protect” their interest amid growing racial and sectional tensions.5 The Witters, in February 1860, crossed the line of trust that was supposed to exist in that guardianship. Having already assumed the “guardianship” of Cora, and knowing that the legislative act was about to be passed, they submitted a fraudulent petition, in her name, to have her officially declared a slave.

Cora fought back. Eleven days after that petition was filed, and three days after the legislative bill became law, she took the Witters to court. She did not go to the probate court, the one that had agreed to her enslavement. To find the sequel to that petition, we have to comb the record books of the state circuit court that served her county. This time Cora had a white friend to speak for her, a Virginia-born planter who had been her previous guardian before the cabinet-maker Henry Witter and his wife Elizabeth, a “teacher of painting,” lured her into town.6

Cora, a free woman of color, by her next friend, Charles L. Easley, files petition saying “She is a free woman of color under the age of twenty-one years, and that she was born free and has always been regarded and treated as free until within a few days past. She is now retained by one Elizabeth C. Witter as a slave. ... She is the child of a free woman of color named Laviny and ... has resided for many years past in the State of Alabama as a free woman ... .”7

The circuit court responded by ordering Elizabeth Witter to post bond for $3,000. (Following the custom of the time, the bond would have been set at twice the value of the “property” being litigated.) Witter was ordered to appear at the next term of court for a hearing on the legality of Cora’s alleged slavery. At that hearing, Witter and her husband “denied the truth of the allegations,” while Cora stood firm in her charges. Both sides presented their evidence, waived their right to a trial by jury, and put their trust in the judge.

The Alabama court sided with Cora. The judge’s decree declared “that the law is with the said petitioner Cora and that ... Cora is not, and never was the slave of said Elizabeth C. Witter, but is and ever has been free.” The Witters were charged with the cost of the suit.8

Cora had also lost her home and her employment. Easley took her and her two infants back to his plantation, where the 1860 enumerator placed her, her two multiracial babies, and an unmarried white blacksmith in the Easley home. Her brief stand before her county's court of justice did accomplish one small good for others. It would be a year before any other resident of Chambers County attempted to enslave a free person of color under the authority of the 1860 legislative act.

No. A record cannot “speak for itself.” Every record has to be put into the context of the law that underpinned it. Still, even knowing the law under which the Witters attempted to enslave Cora—even doing thorough research to ensure that we found all records created by and about this young woman—even that would not have enabled us to correctly interpret Cora’s situation without one thing more. We also needed to study her in the context of others of her political and social class. Their plights and their fates helped us understand Cora and her circumstances.

1. Chambers Co., Ala., Probate Minute Book 8: 613; Office of the Probate Judge, La Fayette. The Chamber County records used in this QuickLesson are not yet available on line.

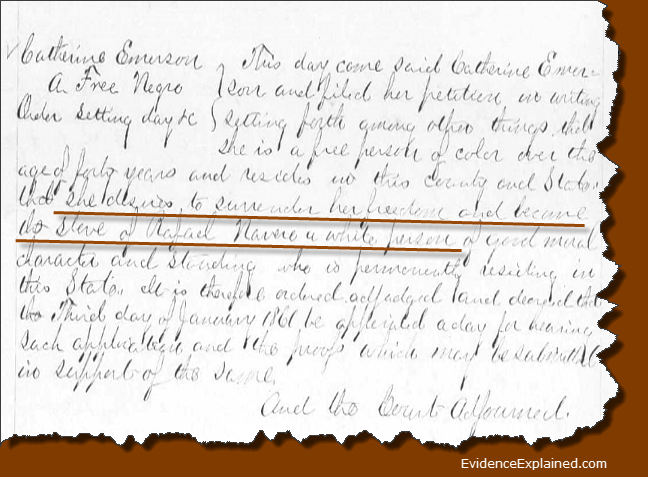

2. Catherine Emerson, whose petition illustrates this QuickLesson, was one of those Mobilians. For the clerk's recorded copy of her petition, see Mobile Co., Ala., Minute Book 12: 368, Office of the Clerk of Court, Mobile; imaged in "Alabama Probate Records, 1809–1985," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 13 November 2015), path: Mobile > Minutes 1858–1861 vol 11–12.

3. J. Boardman, compiler, Acts of the Seventh Biennial Session of the General Assembly of Alabama ... Commencing on the Second Monday of November 1859 (Montgomery, AL: Shorter & Reid, State Printers, 1860), 63–64; imaged at Google Books (https://books.google.com/books?id=5bU3AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=63&f=false : accessed 13 November 2015).

4. For others, see Chambers Co., Probate Minute Book 8: 613–14, 643–48; 9:463, 473, 765–67. A search for these petitions was made in all surviving record books of all antebellum Alabama counties by the late University of Alabama historian Gary B. Mills and I—a project partially funded by two UA grants. The groundwork laid by this project in Mobile and Baldwin Counties was then built upon by UA graduate student Christopher A. Nordmann for his doctoral thesis, "Free Negroes of Mobile County, Alabama" (Ph.D. diss., University of Alabama, 1990).

5. For example, see Chambers Co., Probate Minute Book 5: 29, 207, 214–15, 257, 266, 386–87, 414–15, 447–48; 7: 87, 445–48; 9:69–70; also Petition Record 1: 7, 10, 121, 124, 199–202, 211–112, 291. Thirty-three other Chambers County free people of color were caught up in these legalities, including other members of Cora’s family. The identities of all the ensnared individuals are

- Alexander, George, Henry, Prince, Samuel R., and Lavina Bellanger (aka Bellamy; all under the guardianship of John B. Barnett);

- John (guardian: William Smith);

- George and his wife Susan (guardian: William T. Davis and wife Elizabeth);

- Hannah and her children Ernest, Louisa, and May (guardian: Augustus Hammond);

- Eliza Jones and her daughter Mary (guardian: Zachariah Corley);

- Fanny LeMasters and her children Richard, Charles, and George (guardian; Thomas C. LeMasters);

- Franklin Moree (who Nathaniel King attempted to sell as a slave but was thwarted by the white Samuel D. Watson);

- Margaret Roundtree and her children Eliza, Albert, and Henrietta (guardian: A. W. Roundtree);

- the aging Sina; her daughter Martha and Martha's child Sarah Elizabeth Margaret; Sina's daughter Laura; and Sina's daughter Betsy with children Wesley, Matthew, Bob, and Henry (guardianship dispute between Benjamin F. Cox and Cornelius Rea and later enslavement petitions by Rea).

6. For the Witters, see 1850 U.S. census, Chambers Co., Ala., Chambers Court House, p. 4, dwelling/family 25. For Easley, who was from the rural community in which Cora grew up, Oak Bowery, see p. 115, dwell./fam. 784. The Witters of this paper are of no connection to the Witters about whom I have frequently written elsewhere.

7. Chambers Co., Circuit Court Record Book 21: 784–86; Clerk of Court’s Office, La Fayette.

8. Ibid.

How to Cite This Lesson

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 23: No. Records Do Not Speak for Themselves,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quick-lesson-23-no-records-do-not-speak-themselves : [access date]).