Analysis and citation. Citation and analysis. In historical research the two are inseparable. Each is the egg that creates a chicken that creates an egg that creates a chicken. Amid that cycle, a defect in either the chicken or the egg can have long-term consequences.

As students, we learned that source citation was a chore we must do for two reasons:

- to provide “proof” for what we write; and

- to enable others to find what we used.

This classroom explanation misses the most critical point of all:

- Citations are an analytical tool we use to help ourselves reach accurate conclusions.

As researchers, we love sources. They provide answers to our burning questions. But they don’t provide proof. The answers they give us may be untrue. They may be incomplete. They often contradict each other.

Each time we find a source, we must analyze it to determine what it is. Then we identify it. That physical analysis and identification of our source is expressed as a citation. At publication stage, that citation is typically stripped down to the bare minimum needed to relocate the source. But, in the research phase, the details we capture in that citation provide the foundation for evaluating or analyzing the information that source provides.

As our research expands to include many sources, we find conflicts between them. Again, the details we have captured about each source provide a framework for analyzing our body of evidence. In the end, the proof we offer can be no better than each individual source upon which our conclusion is based.

For these reasons, a thoughtful identification of each source, at the time we use it, will do two things:

- provide standard citation details for the source and its location; and

- identify the source in such detail that we know exactly its nature, its strengths, and its weaknesses.

CASE AT POINT

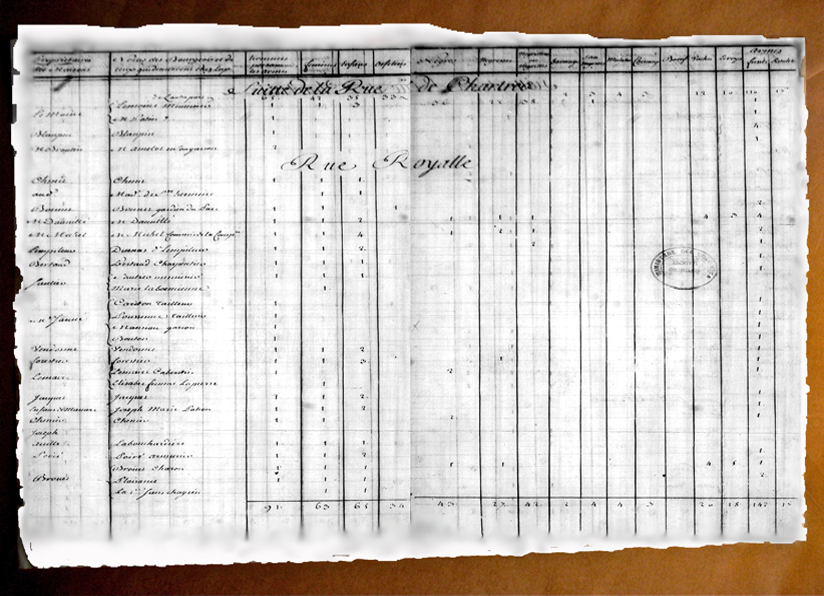

The document that introduces this QuickLesson illustrates the reasons why a citation needs to reflect the nature and quality of the source.1

Censuses were critical records in the early colonies of the New World. Those that survive are vital to historians who attempt to understand the past. Most known censuses exist, today, in various formats—notably originals, duplicate originals, images, transcriptions, abstracts, and databases.

Because these censuses are fairly ubiquitous, even on the Internet, many researchers cite them generically—e.g., “1704 Census of Maryland” or “1732 Census of New Orleans,” or “Twelfth Census of the United States, Teton County, Montana.” Thoughtful researchers, however, know that all versions of a record are not created equal. Thus, in their research notes, they carefully identify not just the source but the version they used.

For decades, students and scholars of Colonial Louisiana history have rested conclusions upon a staple source: a two-volume work published in 1970 by the late Glenn R. Conrad. As a university historian, Conrad labored to identify and obtain, for his institution, documents critical to the French establishment of Louisiana. To make those materials even more accessible, he and his students transcribed many of them—principally censuses, military records, and ship rolls—then published them in a pioneer work, First Families of Louisiana.2

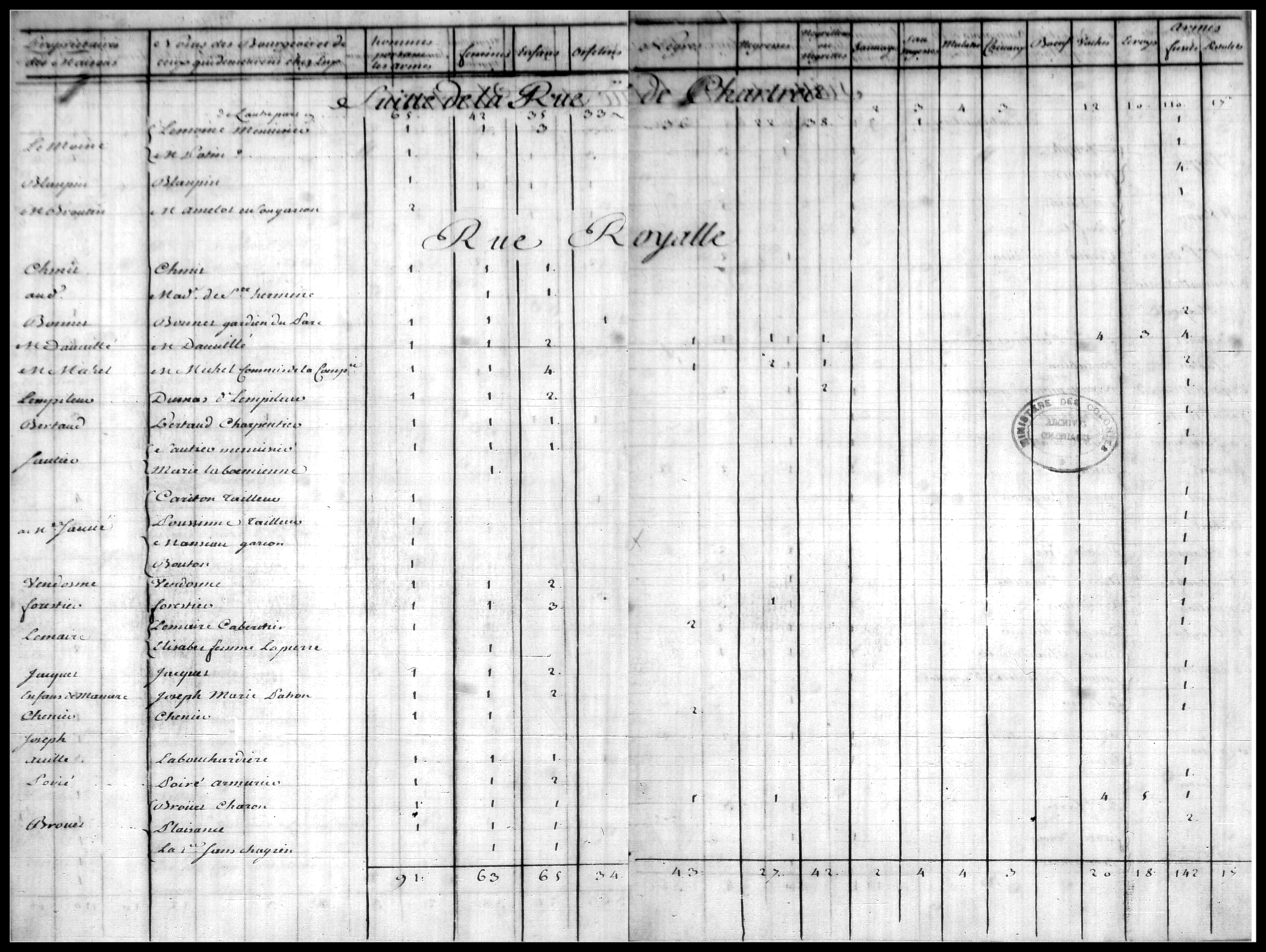

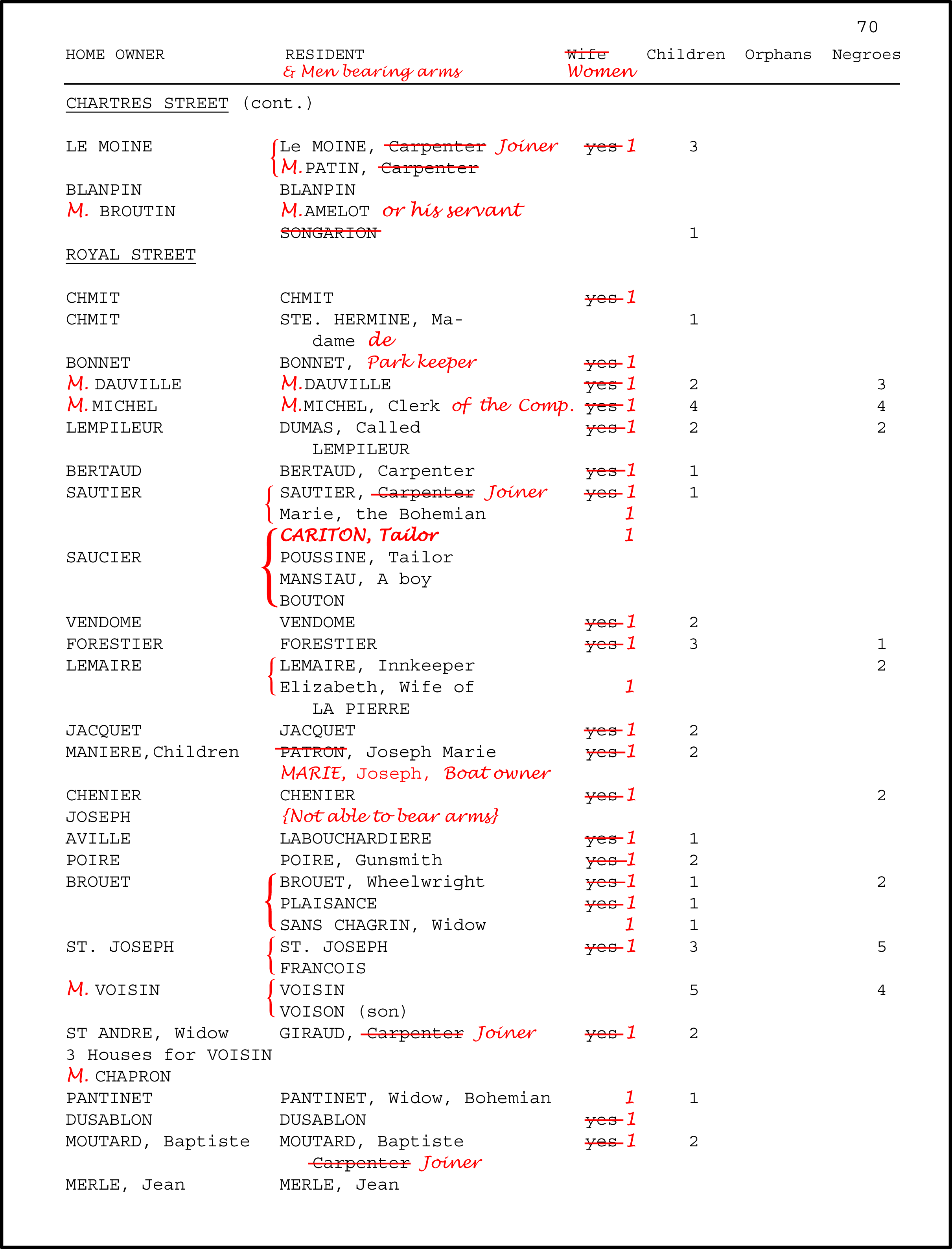

One of the documents represented in Conrad’s work is the January 1732 census of New Orleans. Conrad presents it as a translated transcription, laid out in a tabular form that ostensibly replicates the original. A comparison of the published version with the original manuscript clearly demonstrates the folly of relying upon derivative works.

The two images, below, are representative of the entire record. The first presents an image of manuscript page 8. The second is an annotated image of Conrad’s corresponding page, which offers his “transcription.”

Among the significant differences, we see these:

- The tailor, Jean Cariton, is missing entirely from the transcribed 1732 census, implying that this man, who was first enumerated in 1721, has died or left the colony.3

- Several columns of data have been omitted and other columns have been consolidated.

- All blacks, multiracials, and Native Americans, regardless of ethnicity or gender, are lumped into one column called “Negroes.”

- The column for “men bearing arms” has been renamed “Residents.” As a consequence, the listing for the one-named man Joseph implies that he is not a resident. Worse, it does not indicate the fact that he is considered incapable of bearing arms.

- The column that appears as femmes on the original (i.e., women), has been renamed “wives” and, in lieu of the number of females, it substitutes the word “yes.” As a result, various male householders with women in their home are assigned “wives” even though they were not married at the time. On other pages, single women whose surname was prefaced by La in the custom of the time, appear as a male with a wife.

- The initial “M” that appears before some of the names has been omitted in the transcription. That initial represents the word Monsieur, a title of address that was used for officials of the colony, concessionaires, and other elite males. By omitting the title, the transcription obscures the class differences that prevailed in that society. And, because most entries carry only a surname, the elimination of the title also ambiguates the identities of some males with others of the same surname.

- Occupations are sometimes omitted. On this page, Bonnet, the park keeper, demonstrates the problem. Other individuals on the census whose occupations were omitted included the colony’s greffier (clerk of court) its huissier (bailiff), one of its patrons (small scale boat owners), the oeconome (manager) de l’hôpital, the bedeau (church beadle), and both of the colony’s orfèves (goldsmiths)—all posts and trades significant to the local economy. In more than one case on this census, the omitted occupation is needed to disambiguate individuals listed by the same surname.

- In several cases, as illustrated above by the patron Joseph Marie (Marie was his surname), occupations are presented as the actual surname of the individual

- In almost all cases, the menuisiers (joiners) are simply called carpenters. The original census clearly distinguishes between those occupations, as illustrated above by the consecutively listed men Bertaud, Carpentier and Sautier, Menuisier.

Whatever our practice, our citations should clearly distinguish original documents from derivatives and distinguish between types of derivatives and their creators. Then, when conflicts appear within our research notes, we are far better equipped to decide which assertions carry the greater weight. And, when stalemates arise, we have sufficient data to identify the weaknesses in our research that we need to address.

1. “Recensement General de La ville de la Nlle Orlean, a tant des hommes portant armes, femmes, Enfants, Negres, Negresses, negrillons ou Negrittes, sauvages, sauvagesses, Mulatres, Mulatresses, que des Chevaux, Boeufs, Vaches, Ecroys, and Armes, fait au mois de Janvier 1732” [General census of the town of New Orleans, indicating the men bearing arms, women, children, Negro men, Negro women, Negro boys or Negro girls, male Indians, female Indians, mulatto males, mulatto females, as also the horses, oxen, cattle, other barned animals, and arms, made in the month of January 1732], Archives Colonies G1 464, Archives Nationales, France.

How to cite this lesson:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 1: Analysis & Citation,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-1-analysis-citation : [access date]).