“What citation template do I use?” the student asked—just before launching into his complaint. “Research would be fun if it weren't for citations. They're too nitpicking. There are too many formats. History researchers need software that has no more than ten templates and will automagically decide which one best fits.”

Okay, Dear Student. You’ve vented. Can we now have a friendly little Attitude Adjustment Session?

Attitude Adjustment 1

Citing sources is not just a matter of how to format a bunch of tedious details. We only think that way because, way back in sixth grade, Miss Pain told us we had to cite our sources so that Doubting Thomas would know where we got our facts. That turned source identification into a chore we do for others, instead of a benefit we do for ourselves.

The real problem, then and now, is that “facts” aren’t facts, and all “facts” aren’t created equal. Recorded “facts” are nothing more than assertions somebody made. The more research we do, the more conflicting assertions we find. The whole point of research is to try to figure out what the truth might be.

That, Dear Student, is the reason for citations. Without knowing the quality of the source, how can we decide what set of “facts” to believe?

“Without knowing the quality of the source, how can we decide what set of 'facts' to believe?”

Attitude Adjustment 2

The real question is not What template should I use? It’s What kind of a source do I have? That’s the question we need to consider at the moment we find anything that makes us go Aha!

That point of discovery, the moment we have actual contact with the record, is the time to stop and think about what we have found. That’s the point at which we need to define our source. That’s where we need to describe its physical condition and the characteristics that suggest authenticity and originality—or don’t. That’s when we analyze the collection or record set in which we found this item: its arrangement, its completeness, its provenance, and the other characteristics that affect the quality of the information we’re about to extract.

“The real question is not What template should I use? It's What kind of a source do I have?”

Attitude Adjustment 3

Descriptions in a citation? Yes. And, yes, that’s something we rarely see in a citation template. It’s also something we may not use in whatever citation we end up publishing. That's because there’s a serious difference between citations in our working notes and the citations that end up in our finished product. It’s the difference between input and output.

Reread Adjustment 1. The real point of citations is to help get as close to the truth as possible. As researchers, we don’t just gather data and write it all up. Research calls for continual analysis of our findings and correlation of details between many sources. That process of evaluating and comparing is where we need all that source information we gathered at the point of contact. Whenever we eventually get to the point of writing something conclusive, we'll draw upon those details to explain why we have reached the conclusions we put forth.

See? Citations are all about information, not just formatting. Need convincing? Read on.

“Citations are all about information, not just formatting.”

CASE AT POINT

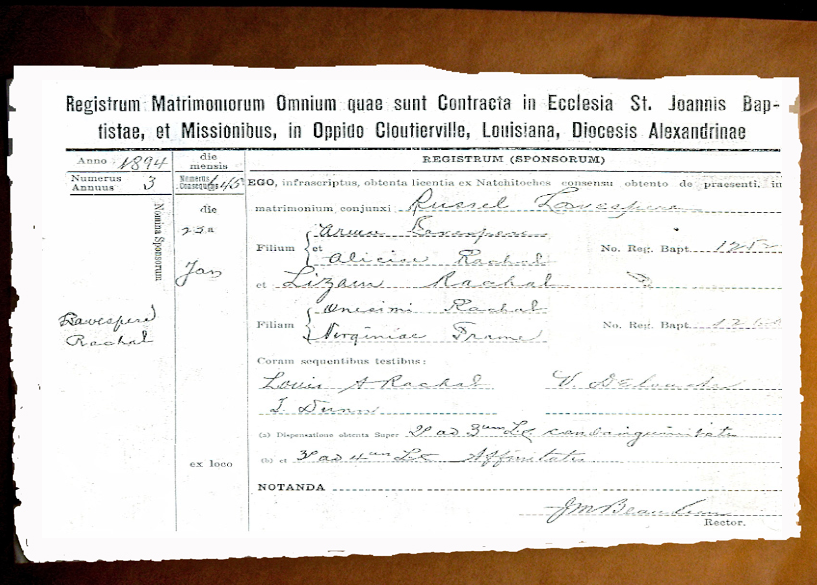

In the 1970s, a clouded land title prompted an attorney to order a "marriage record" from a parish church in Louisiana—St. John the Baptist Church in the village of Cloutierville, civil parish of Natchitoches. According to the "Certificate of Marriage" provided by the priest, Lize Rachal, daughter of Onésime Rachal and wife Virginia Frame, married Russell Lavespère on 23 January 1894.

That certificate created havoc with the legal matters under dispute. Half the details attested on the document were false, even though the certificate was to be evidence in litigation before a court. A legal brief prepared by one set of attorneys supplied a source citation for the document; but, as noted under Adjustment 1 above, citing one’s source does not prove the “facts” asserted in any piece of evidence. The validity of those facts is established by a thoughtful analysis of the record, its characteristics, and the context under which it was created.

“Citing one’s source does not prove the “facts” asserted in any piece of evidence. The validity of those facts is established by a thoughtful analysis of the record, its characteristics, and the context under which it was created.”

The Context of the Record

St. John's was created in 1847. Its population was mostly French Creoles—both blanche and de couleur—with a sprinkling of Hispanics out of Texas and Anglo incomers from the “American” states. Parish priests for the rest of that century were also French. Not surprisingly, most maintained their registers in that language: Baptêmes, Mariages, and Enterrements.

As the twentieth century rolled in, that culture fell out of favor. New priests spoke English. New nuns opened a school and disciplined students who lapsed into a French patois. Publishing houses had begun to provide preprinted registers, whose pages carried numbered certificates couched in high-church Latin, with handy blanks to fill in with details for the sacrament being administered and still more blanks for cross-referencing each sacrament to others each parishioner had received.

So it was that St John’s nuns labored to replace and retire the old French record books. The scrawled and lackadaisical actes of Père Jean Marie Beaulieu, who tended the parish for several decades in the late 1800s, posed a special challenge. For marriages, his actes named the two parties. Rarely did he bother to identify parents of either spouse.

Beaulieu’s omissions did not deter the nuns whose new registers had blanks begging to be filled. For each marriage entry in the new Latin registers, they diligently combed the old baptismal registers, ferreting out infants in an appropriate time frame who bore the “right” name. When faced with multiple same-or-similar name possibilities for parishioners who had already passed on, they asked the old timers of the parish to recall who might be the parents of a particular wife or husband. One way or another, they filled most of the blanks.

The Lavespère-Rachal fiasco

This was the context against which St. John’s pastor responded to the lawyer’s request for marriage records of Onésime Rachal’s children by his wife Virginia Frame. Like all the twentieth-century priests before him, the pastor turned to the Latin books, rather than the original registers whose inscriptions lacked even an index. With minimal effort, he located a "marriage record" for one of them and created a certificate, duly certified.

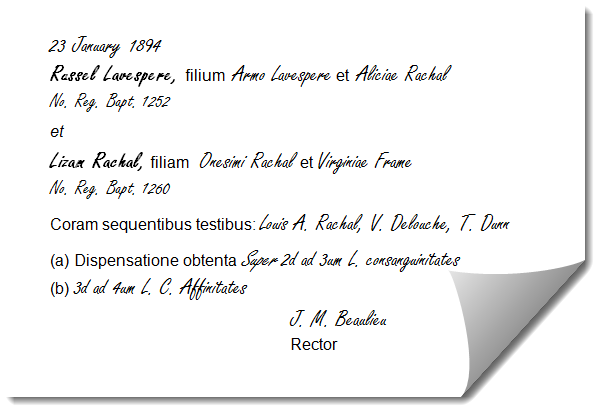

For the daughter Elizabeth, called "Lise" or "Lize," that Latin register offered the following data, as penned by the parish nuns:1

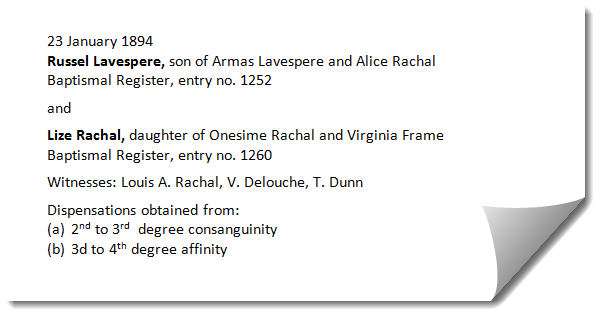

Or, in English:

The certificate created by the Cloutierville pastor presented these facts in English. His cover letter stated that the record came from “Marriage Book 1.”

The legal brief that sent the church’s certificate to the court cited the certificate in roughly the same pattern demonstrated by EE 7.24.2 It did not question the exactness of the register's title or its language. Nor did the attorneys question whether the record book was actually the original. On both sides of the litigation, attorneys simply took at face value the details given on the church-issued certificate.

That trust was incredibly naive. It almost distorted justice. In short:

- The Lize Rachal who married Lavespère in the Cloutierville church was not the daughter of Onésime Rachal and his wife Virginia Frame.

- The Anglo-French Lise Rachal, born to Onésime and Virginia, actually married a different man in a civil ceremony in an adjacent parish.

- The Lavespère offspring were not the legal heirs to the mineral rights being litigated.

So what happened here? How did the church err?

Correcting the Record

Our frustrated student was partially right. Creating a citation to the actual book from which the certificate data was taken would have been more tedious than just citing a generic "Marriage Book 1." But the thought process that underlies the creation of a careful citation triggers a slew of questions about the reliability of the “record” being presented to the court and proves why we need to analyze a record for credibility issues.

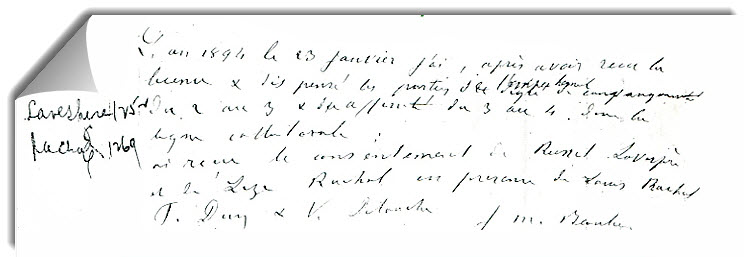

When we compare the Latin-language record to the original marriage acte entered by Father Beaulieu at the time he performed the ceremony, we immediately see the source of the problem.

“In the year 1894, the 13th [not 23rd] of February, after having seen the license and dispensed the parties from the impediment of consanguinity in the 2nd to 3d degrees and affinity in the 3d to 4th degrees, I have received the mutual consent of Russel Lavespère and of Lize Rachal, in presence of Louis Rachal [not Louis A.], P. Dunn, and V. Delouche. [Signed] J. M. Beaulieu."3

The original acte does not name parents for either the bride or the groom. When the nuns extracted data from the French register, the blanks left in the new Latin register had bothered them. So, they supplied the “missing information” by combing the baptismal register in search of infants named Russell Lavèspere and Lize Rachal.

For that male name, they found only one candidate and they did identify him correctly. But they found several candidates named Lise, Lize, Louise, or Elisabeth Rachal—the person critical to the legal case. To narrow down possibilities as to which baptized child would have married Lavespère, they attempted to match every baptized Lise, Lize, Louise, or Elisabeth Rachal with a later burial or marriage record. In the end, they had only one candidate left—the child baptized as Elisabeth Rachal in 1874 to Onésime and Virginia. By elimination, the nuns decided that she must be the "Lise" who married Russell Lavespère.

Woe unto researchers who conclude that “the only one” in a given set of records must be the right one!

The critical clue to this woman’s identity is found in the civil record of her marriage, which Fr. Beaulieu also created when he returned the executed license to the parish courthouse. The clerk's recorded version of Beaulieu's return, also entered onto a preprinted format, tells us this:

PROCESS VERBAL OF MARRIAGE:

Be it remembered that by virtue of a License issued by the Clerk of the District Court of the Parish of Natchitoches, I, J. M. Beaulieu, have celebrated marriage between Mr. Reussell Lavespere and Mrs. Lize Rachal and have joined them together in holy Wedlock, according to law, this 23 day of January A. D. 1894. Parties: Roussell Lavespere; Liese Rachal. Witnesses: V. Deslouches; H. P. Dunn; L. A. Rachal.4

This Lize or Lise Rachal who married Russell Lavespère was a widow. She was not a Rachal by birth. Her birth name, however, went unstated in the courthouse record.

Identifying “Mrs. Lize Rachal”

Two of the witnesses to the Lavespère-Rachal marriage provided the first clues to Mrs. Lize's identity—once we made the effort to identify those men:

- Louis Rachal: On 23 December 1873, he married Angela Delouche, with V. Delouche as witness.5

- V. Delouche: On 29 June 1893 as Vidal Jr., he married Louise Rachal, with Louis A. Rachal as bondsman and witness.6

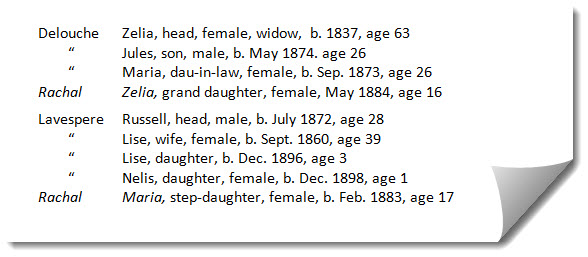

The repetition of names in this cluster—the obvious endogamy of the marital choices—strongly suggests Delouche for Mrs. Lise’s identity. The first census taken of the Lavespère-Rachal couple, that of 1900, again places "Mrs. Lise" in a Delouche-Rachal cluster. Her new family and the adjacent household appear as follows:7

The details of the family cluster suggest not only that Mme. Lavespère was a Delouche, but also that she was likely the daughter of the widowed 63-year-old Zelia, and the mother of at least two daughters by her former husband: Zelia and Maria Rachal.

Cloutierville’s baptismal and marriage registers—the original registers, of course—confirm this hypothesis:

Baptism:

Lise Deslouches, baptized 19 June 1860, aged 9 months, legitimate daughter of Vidal Deslouches and Zelia Duthil.8

Marriage:

Emmanuel Rachal married Lise Delouche (no parents) 28 January 1879, in presence of Louis Rachal, Joseph Gallien, and Marin Brosset.9

Baptisms of Children for “Emanuel Rachal & Lise DeLouche”

- Eugene Rachal, born 16 November 187910

- Vidalie Rachal, born Nov. 26, 188011

- Marie Rachal, born 25 February 188212 [the child living with her remarried mother in 1900]

- Zelia Rachal, baptized 13 September 1884 at 5 months13 [the child living with her grandmother in 1900, next to her mother and stepfather]

So What Happened to the Real Lise Rachal?

Civil records also suggest why relatively little appears on Onésime and Virginia (Frame) Rachal in the Cloutierville records. In 1852, Onésime took out federal land about 10 miles east of Cloutierville, on both sides of Red River. Months later, part of his land was cut away into the new parish of Winn.14

There in Winn Parish, on 13 January 1893 before a justice of the peace, Onésime's and Virginia’s daughter Lise Rachal married Victor Grandchampt, the son of a neighboring planter.15 This marriage, like that of Lise (Deslouche) Rachal to Russell Lavespère thirteen months later, places the bride in a family cluster that helps to identify her. Her older sister Eugenie Rachal, several years before, had married the widower Eugene Grandchampt, Victor's father.16 Lise's sister was now her step-mother-in-law.

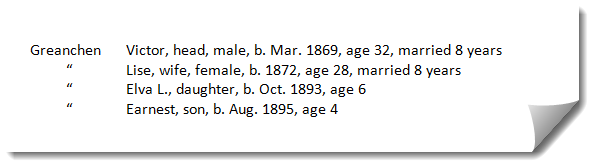

Lise (Rachal) Grandchampt also appears on the 1900 census, in the same ward as Lise (Delouche) Rachal Lavespère:17

The Bottom Line

This QuickLesson has taken us considerably off the path set by the student in his complaint—his question over what canned template to use and his plea for simple citations that would not be so “nitpicking.”

As our student said, research is fun. It still must be nitpicking. Research is not a matter of finding a record that has the right name, assuming it deals with the person we’re looking for, and then plucking a simple citation from our software. That “grab and go” approach will sabotage any research project.

The reason so many citation formats can exist for a seemingly simple item as, say, a “marriage record,” is that records themselves are not simple. They come with many variations.18 They have quirks and flaws that need to be thoughtfully considered, for reasons far more serious than merely choosing a template.

Identifying a record precisely will alert us to quality-control issues. Defining a record as a marriage certificate rather than the original marriage act makes a difference in the credibility of that source. Defining a “church book” as a fabricated register created long after the fact—one with both copying errors and silent additions that are totally wrong—is a critical warning to us that we need to verify the assertions made in the derivative against the original register.

No, Dear Student, the “big issue” with citations is not the difficulty of choosing the right template. The critical issue is the evaluation of the source to ensure that we are using a reliable one.

1. St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (Cloutierville, La.), "Registrum Matrimoniorum Omnium que sunt Contracta in Ecclesia St. Johannis Baptistae, et Missionibus, in Oppido Cloutierville, Louisiana, Diocesis Alexandrinae," entry 645; parish rectory, Cloutierville.

2. An Evidence Style citation for the certificate would be: St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (Cloutierville, Louisiana), Lavespère-Rachal marriage certificate (23 January 1894 marriage); issued 1978, citing "Marriage Book 1."

3. St. John Church, “Marriages, 1855–1905,” unpaginated, unnumbered entries in chronological sequence.

4. Natchitoches Parish, Marriage Book 13:114; Clerk of Court's Office, Natchitoches. Note that this courthouse marriage record—entered into a register—is also a derivative, not an orginal. As a consequence, we see other variations in the identities of the bride and groom. The courthouse record also identifies witness Dunn as "H. P.," rather than "T.," as in the Latin version of the church record, while the original French acte calls him simply "P." Dunn. We should also take note that the courthouse clerk who created the record routinely made his capital-V in a scrolled manner similar to capital E, thereby creating the opportunity to misidentify Vidal Deslouches as "E." Deslouches.

5. Natchitoches Parish, Marriage Book 5:233.

6. Ibid., Book 12:63.

7. 1900 U.S. census, Natchitoches Parish, La., Ward 10, ED 81, sheet 8B, dwellings 134-135, families 135-136.

8. St. John Church, Reg. 1, “Baptisms of Whites, 1847 to 1863,” 1860: entry 12.

9. St. John Church, “Marriages, 1855–1905,” unpaginated, unnumbered entries in chronological sequence.

10. St. John Church, “Baptisms, 1872–1894,” p. 87.

11. Ibid., p. 100.

12. Ibid., p. 109.

13. Ibid., p. 135.

14. Bureau of Land Management, “Search Documents,” database, General Land Office Records (www.glorecords.blm.gov/ssearch/default.aspx : accessed 24 August 2015), “Onezime Rachal,” SE¼ SW¼ S33 T9N R5W, Winn Parish (1 Oct. 1852); also, with Frederick H. Waddell, Lots 4, 5, 6, 7 in S46; Lots 2, 5, 13, in S45, T8N R6W, Natchitoches Parish (1 Sept. 1853).

15. Grant Parish, La., "Marriage Record 1878–1916," 33, Grandchampt-Rachal marriage; Clerk of Court's Office, Winnfield.

16. The actual marriage of Eugenie Rachal to the much-older Ernest Grandchampt has not been found. Their daughter Lodioska, born 18 Oct. 1888, was baptized at Cloutierville as a legitimate child; see St. John Church, “Baptisms, 1872–1894,” p. 186. On 3 April 1893, at Cloutierville, the widowed Eugenie (Rachal) Grandchampt married Alcide Gallion; St. John Church, “Marriages 1855–1905,” unpaginated, unnumbered entries in chronological order. She, her new husband, and her Grandchampt daughter appear on the 1900 census in the same community as her sister Lise (Rachal) Grandchampt; see 1900 U.S. census, Natchitoches Parish, ward 10, ED 81, sheet 16, dwelling 278, family 281. The fact that the two Rachal sisters married a Grandchampt father and son was confirmed in 1977 in an interview by the present writer with Lise’s daughter Lela (Grandchampt) Enright, Port Arthur, Texas; she also confirmed that her grandparents were Onésime and Virginia (Frame) Rachal.

17. 1900 U.S. census, Natchitoches Parish, La., ward 10, ED 81, sheet 23B, dwelling 426, family 429.

18. Thus far, five different "marriage records" have been found for the Lavespère-Rachal couple—each of them with differing data: (1) the Latin "fabricated" church register, (2) the original French church register; (3) the courthouse marriage bond, in derivative form; (4) the courthouse return (aka "process verbal"), in derivative form; and (5) the "Certificate of Marriage" created by the twentieth-century pastor.

How to Cite This Lesson

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 22: What Citation Template Do I Use?” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-22-what-citation-template-do-i-use : [access date]).

Posted 27 August 2015