What was the last book you bought—and why?

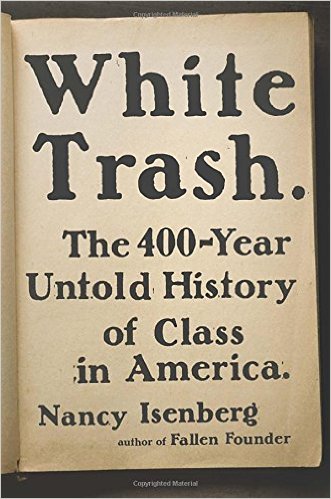

A friend raised this question on social media yesterday—right after Amazon’s delivery left a new book on my doorstep. Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America.

My friend’s why? question triggered a memory. Thirty years ago this spring, a professional research association asked me to give its “official” presentation at a national conference. A history’s-mysteries case-study, they suggested. For my topic, I chose a woman who “just showed up” in Texas in 1856: middle-aged and propertyless—except for a few head of cattle. Mystery had long-swirled around her identity and origin. She was remembered only for the fact that she died of grief, eleven days after the death of her son.

The research had involved a gnarl of challenges—starting with name changes, cultural divides, two generations of illegitimacies, and an astonishing number of moves across America by single mothers in the years between America’s Revolution and its Civil War. New York to Maryland. To Missouri. To Natchez. To Mobile. To Cajun Louisiana. To the wilds of the Ouachita. And then on to Texas for the “fresh start” that lured so many American families westward.

At the end of the presentation, after the more-intimate discussions with audience-members who clustered around for questions, I walked from the ballroom into the exhibit hall. The first booth I encountered was that of a venerable society—the oldest historical society in America. Sitting there was an employee I sort-of knew. He hailed me over. “I’m intrigued!” he declared. “Everybody coming through here for the past half-hour has been talking about that piece of research you did. Tell me, who was this woman?”

I told him, at least the elevator speech version. His response was an elevator-stopper. “But what’s the point?” he asked. “Why waste all that time on a nobody? White trash, it seems to me!”

That’s why I bought Nancy Isenberg’s book. As I quickly rifled its pages just now, I spotted terms such as deplorables, waste people, and the offscourings of society. Squatters. Crackers. Sandhillers. All “hapless victims of class tyranny and a failed democratic inheritance.” (p. 136)

Across forty years of research, I’ve pursued thousands of American settlers who likely heard such epithets aimed their way on courthouse squares and the streets of bustling towns. Many were women such as Margaret and her mother, who struggled to support their children after husbands died impoverished or beat them until they fled with children in tow. Many were honest men, worn down by competition against the more-educated elites who scorned them in memoirs, travelogues, and newspaper editorials.

And so, I’m curious now as to how Eisenberg’s dissection of the “wretched and landless poor” (as described on her book’s jacket) will handle the subject. Will we see America’s clash of classes through the gritty eyes of the Margarets of this world or through the monocles of the elites who, for centuries, have dismissed them as nobodies and trash?

Now … for those of you who are regular followers of our QuickTips blog and wonder where today’s tip lies in all of this, the tip is this: There is no better way to learn America’s history than to study those “wretched and landless poor” (as Isenberg describes them on her book jacket). Their story is the story of America.

Ferreting out the bits and shards of life left by the underprivileged—reconstructing their stories and their lives—will teach us far more about our world than all the elegant memoires and diaries of traditionally pursued history.

Posted 2 March 2017