Trust. That’s such a comforting word. It relieves so much stress. It lifts the burden of being always vigilant, the angst of worry whether something or someone will betray you, or the fear of making a wrong decision.

In historical research, the reality we deal with is 183 degrees different from the rose garden we’d prefer to work and live in. For us, trust is naïve. Trust creates problems of its own. Today’s three images demonstrate that, using an 1800 census record from Greenville County, SC.

The record itself is disturbing, as is every document that reminds us of the human costs of slavery. But there’s another issue here for everyone who attempts to correlate and draw conclusions from the meager records that survive for enslaved households.

Who can spot the problem, using the three records depicted here?

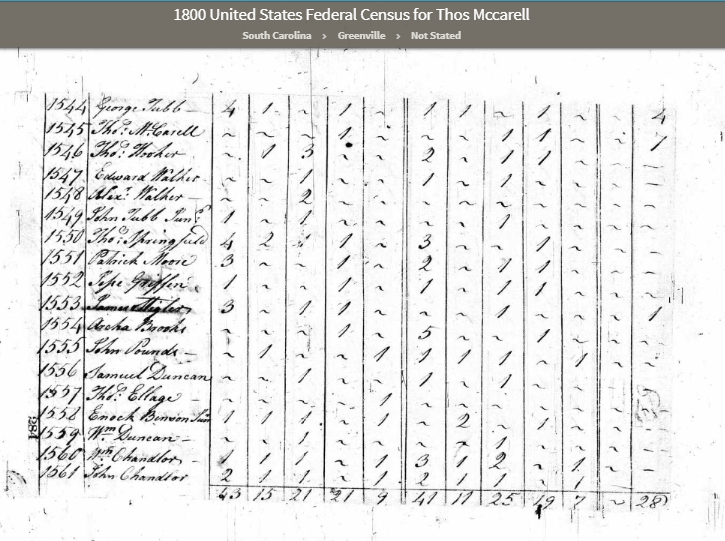

Image of the original page

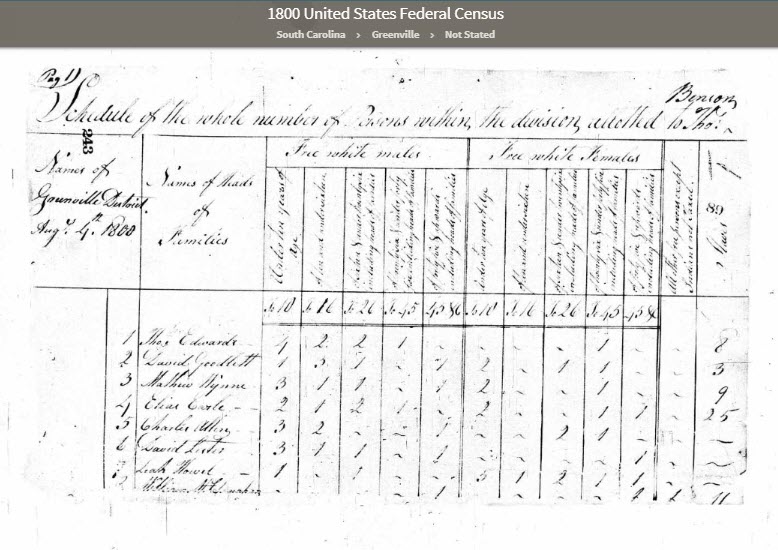

Image of page 1, showing the column headers:

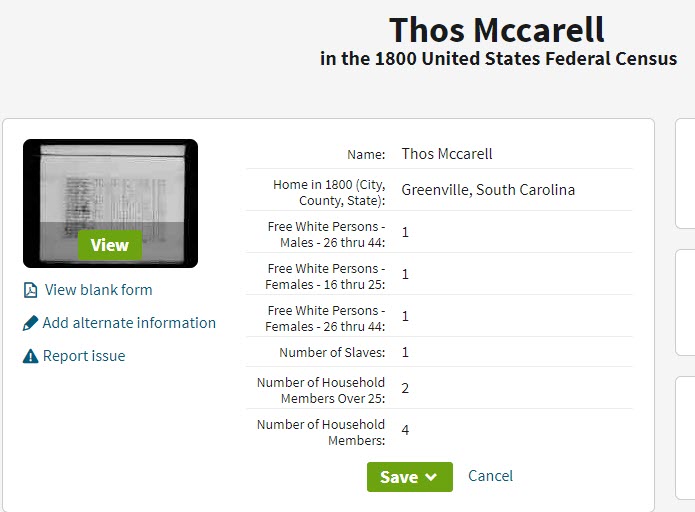

Image of the database extract helpfully prepared by the provider of the images:

Better yet, what other evidence can you present to support your conclusion? (No, I’m not calling for great tons of research here. The point can be proved in 5 minutes or less.)

In this case, I’m not “citing a source” for the images and the extract because my object is not to single out any one provider for criticism. The situation can exist with every record set we use—whether it be Presidential Papers edited by university-based historians or a mom-and-pop website. What’s important is the issue: the folly of trust as a means of short-cutting the deeper thinking that historical researchers need to do. With. Every. Record.

Many of you, I know, would never-ever use Image 3 in your own records. But the truth is: many researchers do—from academic scholars to genealogical newbies, from reporters to legal professionals who feel the printed extracts from the database are “more comprehensible” in the stack of exhibits they present to the jury. (I can vouch for that personally—after staging a “let’s get real” intervention in a significant inheritance case that was about to be lost by an attorney’s preference for “neat” evidence over the scrawled originals created by weary census takers.)

“Neat” for researchers is a four-letter bad word. “Scrawl” can be our friend.

HOW TO CITE: Elizabeth Shown Mills, "Trust: The Researcher's Five-letter Bad Word," blog post, QuickTips: The Blog @ Evidence Explained (https://www.evidenceexplained.com//quicktips/trust-researchers-five-letter-bad-word : posted 2 July 2018).