2 March 2014

For most of us, classroom conjugation of verbs ranked right up there with diagramming sentences as the biggest yawner of grammar classes. The result still haunts us. What we didn’t learn then—or have forgotten since—can make it difficult for others to understand our writing. Here’s a quick tutorial of the type you won’t get from a grammar teacher:

- Verbs tell us about two things: action and time frame.

- When writing, once we state a date or a time frame, we’ve established a reference point. Everything else we discuss about that subject needs to be clearly fixed with reference to this point of time. Imagine a time line that stretches from “way back when” all the way to some point in the future. With our first reference to a date, we set a marker on this time line.

Example:

Silas Schmucker enlisted with Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders on 2 May 1898.

Timeline:

- Whatever happenings we talk about from this point forward will be interpreted in the context of that specific point in time—until we move on to another subject. Therefore, if we move back in time or forward in time, our verb choice needs to signal the direction in which we’re moving.

- After pegging an event to a date, we often need to talk—right there in that same paragraph—about something that happened before or after that date. That’s where the verb tense issue comes in. Our choices can tell us about

- past actions that are done and over with (the simple past tense, used above).

- past actions that aren’t yet completed.

- past actions that were completed before the reference point we’ve just established.

- past actions which, at that reference point, would take place in the future—although we’re not yet done talking about what happened at our reference point.

- Choosing the right verb tense will help our readers understand the events we are unfurling. Conversely, if we choose the wrong verb tense, we can leave our readers confused over when things happened or where they need to mentally position themselves on that timeline.

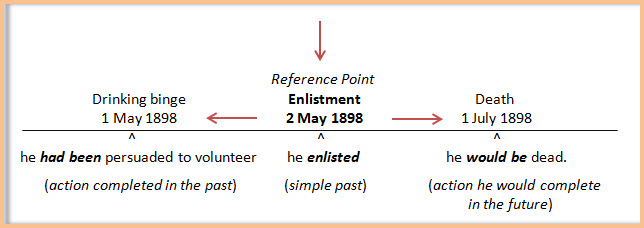

Let’s extend a bit our discussion of Schmucker’s short-lived military career.

Silas Schmucker enlisted with Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders on 2 January 1898. A seventeen-year-old ranch-hand, he had been persuaded to volunteer the night before by drinking buddies at the Menger Hotel bar in San Antonio. By dusk on 1 July 1898, he would be dead, a casualty of the famed charge up San Juan Hill. Within those two brief months, Silas ...

Timeline:

Neophyte writers tend to stick to the plain-vanilla “simple past,” as in

Silas Schmucker enlisted with Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders on 2 January 1898. A seventeen-year-old ranch-hand, he was persuaded to volunteer the night before by drinking buddies at the Menger Hotel bar in San Antonio. He died before dusk on 1 July, a casualty of the famed charge up San Juan Hill. Within those two brief months, Silas ...

So far, there’s no real problem. Despite our lackadaisal verb-ing, readers can understand what’s going on. It’s past this point that we get into trouble. To set up this paragraph’s discussion of his military career, we’ve given the three dates critical to his service record. But we killed him off—and now we need to backtrack to the original date and talk about his life with the Rough Riders before he died at San Juan Hill. If, throughout this paragraph, we present everything in the simple past tense, our readers will feel like we are randomly hopscotching all over the time line, strewing our thoughts as they happened to come to us.

Using the right tense of the verb, each time we choose one, goes a long way toward ensuring that our discussions come across to our readers as clear, well-organized, and logically presented.