28 May 2014

History and literature have spawned many technical words that are not in everyday use. Still, we should know what they represent when we encounter the terms. Today, we consider three of those: Epigraphs, incipits, and explicits.

Epigraphs appear frequently in modern works—quotations placed at the beginning of a volume or the start of each chapter as a thought to "set the stage" for the content of that book or chapter. David Henige's Historical Evidence and Argument, for example, introduces itself with "We do not deal in belief where evidence is available"—a quote from Janet Neel's O Gentle Death. Henige's chapter 3, "The Anxieties of Ambiguities," begins with a longer quote from Julian Barnes's A History of the World:1

"We all know that objective history is unobtainable ... But while we know this, we must still believe that ... it is 99 percent obtainable or ... that 43 percent objective truth is better than 41 per cent. We must do so, because if we don't we're lost [and] throw up our hands at the puzzle of it all."

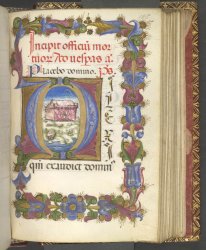

Incipits—taken from Latin for "to begin"—is also a term referring to the words that introduce a piece of writing. However, incipits are the author's own words. The term is typically associated with medieval manuscripts that were left untitled and are now known by their first few words. From the medeival era through the nineteenth century, many Gregorian chants, operas, and works of poetry are known by their incipits—as, for example, Emily Dickinson's "Success is Counted Sweetest ... ."2

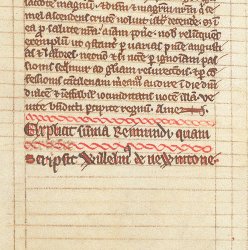

Explicits—taken from the Latin for "unrolled," is a term referring to the closing passage of a written work. As explained by The British Library's Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts: "When cataloguing manuscripts, the incipit and explicit of a text are often cited to aid textual identification."3

1David Henige, Historical Evidence and Argument (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), vii, 15.

2The Complete Poems: Emily Dickinson (Boston: Little and Brown, 1924), part 1: Life; HTML edition, Bartleby.com, Great Books Online (http://www.bartleby.com/113/ : accessed 17 May 2014).

3 British Library, Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts (https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/glossary.asp : accessed 17 May 2014), Glossary, E and I. The illustrations that accompany this blog post are public domain images from the website's glossary; the incipit image is cited there as "Harley MS 2843, f.185"; the explicit image is cited as "Arundel MS 282, f.74."