6 February 2015

Our last QuickTip was a Tuesday's Test. Today, we'll explore a few answers.

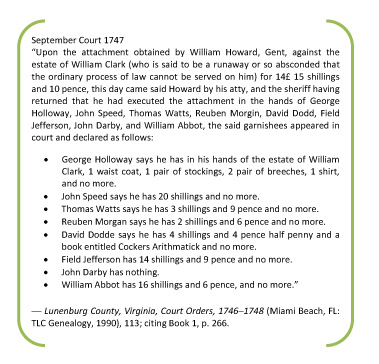

Your challenge was to take a published abstract of a colonial document—a 1747 garnishment from Southside Virginia—and analyze it. How would you interpret the events that triggered the garnishment? What might it tell you about individuals involved? What clues can you draw from it for further research?

Three brave souls from two continents posted their thoughts to help the 1,309 others who scurried to the site for tips. Today, we'll build a bit on the foundation Michelle, Yvette, and Jade have laid—starting with these two questions:

- Why would these men, individually and collectively, owe William Clark the items and amounts they owed?

- How would the court know that each of these men were indebted to Clark? On what and whose knowledge would the judge have issued an order to the sheriff to summons each and all of these 8 men to appear at the next term of court to declare, in public, exactly what they owed this rogue who had absconded?

In a society that had no local credit union or savings & loan, many men with cash on hand did make loans to neighbors. We see lists of those debts-due in many probate files. But the document, here, was not a probate file in which Clark’s administrators were seeking repayment on the basis of promissory notes they had found in whatever bundle of important papers Clark died leaving in his Chest of Important Stuff.

As an absconded debtor, Clark’s whereabouts were apparently unknown. Otherwise, the “gentleman” William Howard would have sued Clark in his new place of residence. As an absconded debtor whose whereabouts were unknown, Clark would not likely have written back to the court to say, "Oh, by the way, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H owe me money that I didn't bother to collect, and I left my britches at so-and-so's house; so if any creditors want whatever I owe them, they can just go after the other guys instead."

What then would be the alternatives?

If, perhaps, Mr. Bigwig Howard had posted a notice on the tavern door asking people to voluntarily come forward to confess they owed money to Clark (so that he—Mr. Bigwig—could take legal action against all those other blokes to get the money the miscreant owed him) how effective do you think that would have been?

Not very. Most men on that frontier would have decided Howard's problem was between Howard and Clark and that they had no hound dog in that hunt. In fact, in their society where cash was short, debts were rampant, and people were actually jailed when they couldn't pay,1 odds are those men would not have had the spare shillings and pence to pay those sums when they were hauled into court for the benefit of Mister Howard, Gent., to whom they owed nothing in the first place.

So ... how would the courts know who owed money to Clark? Obviously, Clark had a trade or profession for which people did not pay cash at the time the service was rendered—and he operated within a confined sphere, so that people in his community knew who he did business with.

What might that trade or profession be? The document abstract gives one clue: the arithmetic book that Jade noted. Very few people in their society would have owned an arithmetic book. School masters or tutors were the usual exceptions. That reasonably answers our first question.

If Clark were a tutor to neighborhood children, then the neighborhood likely knew whose children he taught. That reasonably answers our second question.

If Clark were a tutor to neighborhood children, then the neighborhood would also know which family he boarded with. In fact, that thought was likely the first one Clark’s creditor had: Go to the absconder's known place of residence and ask what he had left behind. Or, more likely, he would have sent John Speed—who, once we look him up, turns out to be the local constable—to do the legwork for him.

If we deduce from this document that Clark was likely a tutor who boarded with Holloway and left an arithmetic book at the home of one of his students, whose father also owed Clark for lessons, then What might we deduce about each of the other men on this list?

For starters, each of these men should be someone with at least one child of educable age.

Virginia’s Southside (the then-new county of Lunenburg, specifically), is an area with limited surviving records. There are deeds, but historians who study Colonial Virginia tell us that most men in that place and time did not own land.2 There are court records but, for most actions, the details are even sketchier than the ones this abstract gives us. There are tithable rolls, incomplete, but they tell us only the number of tithes (males over 16) that a man was responsible for.3 And there are no birth, marriage, or death records—unless the dead man left an estate to probate.

So, let us say we are tracking someone whose name appears on the list—Thomas Watts, specifically—and the Lunenburg records tell us only that

- No contemporary deeds carry his name—at least not in Lunenburg.

- A man of this name signed over his wolf-head bounty to Thomas Speed in December 1746.

- A man of this name was given a wolf-head bounty in 1749 by William Howard—one he signed over to Field Jefferson’s son-in-law, Delony.

- A man of this name is a 1748 tithable in Delony’s district—along with Field Jefferson, George Holloway, Reuben Morgan, David Dodd, and John Speed—and that Thomas Watts paid his own 1 tithe.

- A man of this name is a 1749 tithable in William Howard’s district, with his 1 tithe being charged to "John Earl."

- A man of this name is a 1750 tithable in William Howard’s District, paying his own 1 tithe.

- A man of this name is a 1751 tithable in Field Jefferson’s district, paying his own 1 tithe.

- He then drops from Lunenburg records.

Then:

- The cluster of names suggests we are likely dealing with the same man.

- The fact that he owed exactly 3 shillings and 9 pence to a man who appears to be a neighborhood tutor suggests that this Thomas Watts was old enough to have at least one educable child in September 1747—ostensibly, at least one aged 5.

- Even though he appears not to have owned land and nothing else of record aside from an occasional wolf-head bounty warrant, we can't assume he was, say, an unskilled day laborer or a squatter of the yeoman class—otherwise, the odds weigh waaaay against him having the funds (or even the inclination) to educate his children.

All things considered, where would you now go with this expanded set of facts and deductions?

1. As a fun fact from these same court minutes: Order Book 4:196-97, for example, has debt suits against Field Jefferson and Thomas Jefferson—the latter of whom is said to have absconded, leaving 3 horses in Field’s possession.

2. For example, see David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 374, wherein he reports, "The bottom 60 to 70 percent of Virginia's male population owned no land at all, and very little property of any other sort."

3. But, of course, a rigorous analysis of tax rolls will usually allow us to deduce a number of other useful things.

The Sequel

I did neglect a likely direct connection between the debtor William Clark and the arithmetic book.

Elizabeth's theory is also supported by Darby's having no debt listed -- it helps to see John Speed as going around a neighborhood, knocking on doors to locate debts to Clark. Possibly Darby did have a small debt to Clark, and Speed was able to collect it.

Clark's leaving the book and clothing suggests a hasty departure rather than an intentional move to another domicile. Was there an impending marriage, or was he fleeing the large judgment against him in favor of William Howard? The itemized debts to Clark only amounted to about 1/3 of what was owed to Howard, and the remaining debt to Howard might have resulted in really adverse consequences for Clark.

I still find the nature of the debt to Howard of interest. Was it for an extended period of room/board, fines for non-participation in road work or militia musters, rather than for real or personal property (which could have been resold or returned to Howard)? Or was it a money debt resulting from some estate matters which Clark had left unfinished, such as a distribution or fees?

Great thoughts, Jade.

Great thoughts, Jade. The one point on which I might differ (perhaps I'm misunderstanding your intent) is the possibility that Speed, as constable, would have collected money from one of those who owed Clark. I'd argue that he could not do that without a court order and that the order at this point of the case was for the men to come into court and declare what they owed to Clark. I see no legal channel, at this point, through which Speed could have collected money from one of them and given it Howard to officially reduce a part of Clark's debt to Howard.

Garnishments

As of when the garnishees received the writs of attachment from the Sheriff, they were on notice that the stated sums were due and payable. I see no reason why one of them might not have handed over what he held at that point, although still obligated to appear in Court and account for his debt. If Speed did collect any of the debts, he would have given a receipt for the garnishee to present in Court. The amount owing to Howard may already have been reduced by any amounts received by Speed.

I wonder if Speed carried around a bunch of blank writs (signed already by the Sheriff), which he filled in with names and amounts where appropriate during his tour of the neighborhood. I wonder also what incentive the garnishees had to tell the truth regarding amounts owed to Clark. Of course there was neighborhood gossip.

The quoted item is an abstract, and may not give all of the details that might be of interest, such as "2 shillings, paid over to Speed."

This is an example of where the costs of collection might have exceeded what was retrieved. Even if a kettle or crockery or two shoats were seized in lieu of cash, there was the expense of selling same, and Court costs such as recordation fees, etc.

Thanks for your thoughts, as always,