You’re puzzled. An online writer has provided a link of interest. There, you see an image of a record. But it is presented out of context, leaving you unsure of what you have or how much credibility you can give it. The URL suggests that it is posted at a respectable site—a state archives, no less—so you’re inclined to trust it. Still, you hear the echo of a thoughtful teacher: Do you really understand what you have found? If not, you may miss something critical.

CASE AT POINT

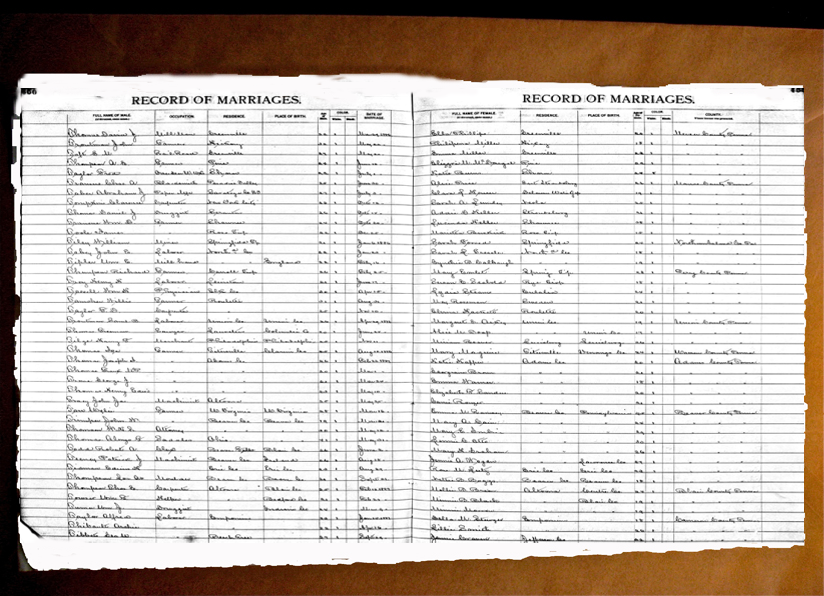

The image in this case would excite any biographer. The personal details for each person are core facts all researchers need to identify people correctly: full name, occupation, place of residence, place of birth, age, color, date of marriage, and county where license was procured. The source is clearly a two-page spread from a bound register that records marriages. All entries are for one letter of the alphabet, using surnames of the males. The entries are also grouped by county, thereunder chronologically between 1885 and 1890.

Okay, we think. We’ve found a statewide marriage register covering, perhaps, 1885 to 1890. So: how do we cite what we have found?

Into the Rabbit Hole

That question is where our maze begins. This exploration of it will be generous with its images, so you can follow us through every tunnel.

The image depicts two pages isolated from the book to which it obviously belongs. The image provides page numbers. It also provides page headers. We’re well aware that page headers often differ from a book’s actual title. So what's the title we need to cite? Who or what agency created this register? Is it a record book with known problems or one most researchers trust?

Identifying the Register

What seems to be the easiest issue to resolve—identifying the book itself—opens up our rabbit hole. Any time we face this identification issue at a website, we can typically solve it through one of two approaches:

- If the structure of the website offers a backward-forward mechanism, we backtrack the page images to the start of the book. There the imagers should have shot the book’s cover or title page. In this case, backtracking pages leads only to page 1.

- We backtrack the URL by taking off one extension at a time, until we reach a web page created by the provider to identify that collection of images.

Backtracking the URL

The URL in this case is moderately long:

http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r14-25RecordMarriages/r14-25RecordMarriagesMale%20539.pdf

Eliminating the last section—everything between the last slash—leads to nothing but the Internet’s ominous 403 message: Forbidden: Access is denied. Undeterred, we lop off another section, r14-25RecordMarriages/ and hit the same hex sign. The third lop, dropping that wee di/, breaks through the barrier.

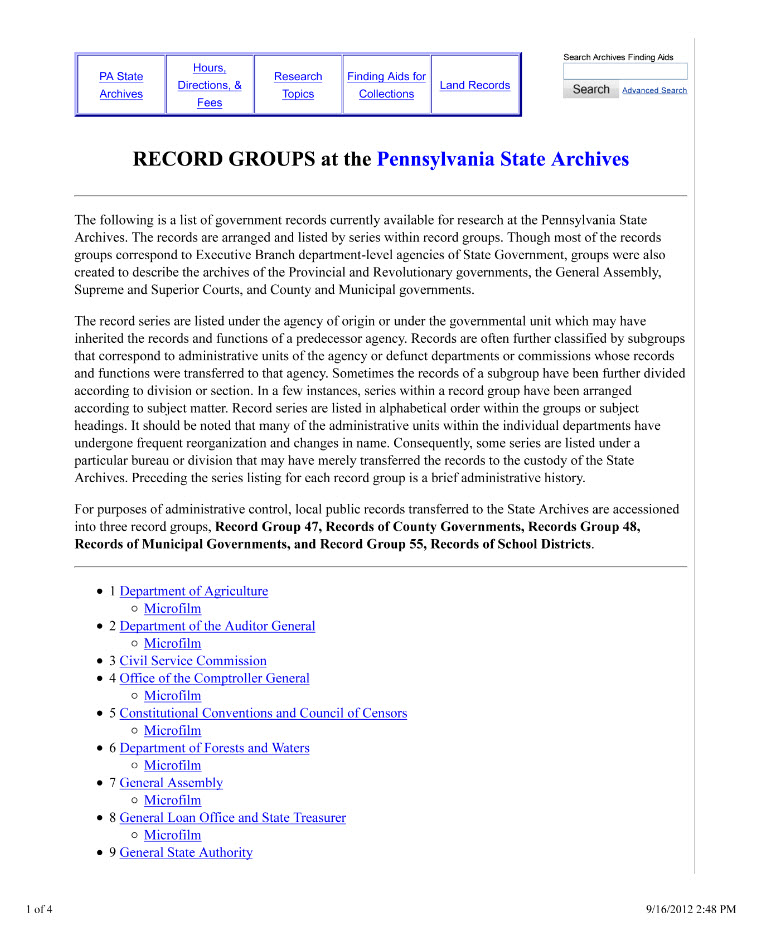

Here, at http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/ our reward is an HTML page titled

“Record Groups at the Pennsylvania State Archives”

We see nothing here about the image that snagged our interest, but it’s still a valuable page. Following the common system for U.S. government archives, the Pennsylvania State Archives divides all its holdings into record groups. That’s what the “rg” represents at the end of our shortened URL. This particular webpage lists all eighty-three of the record groups into which Pennsylvania’s state-created records are organized. Each item on the list offers links to fuller descriptions and lists of available microfilm. But which of the eighty-three is the one we need?

Two parts of the URL that we lopped off suggest the identity of the relevant record group:

- r14-25RecordMarriages

- r14-25RecordMarriagesMale323.pdf

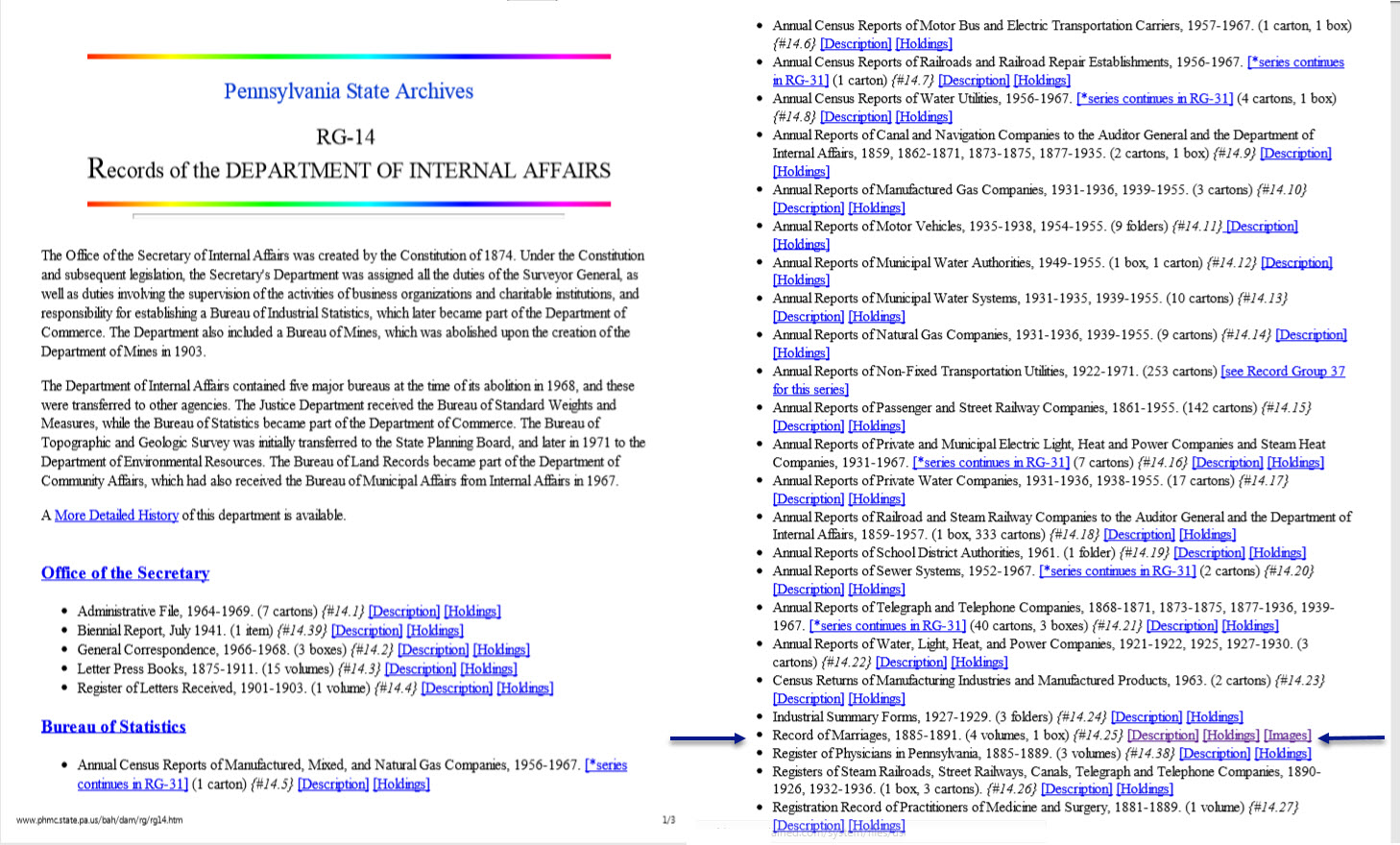

Choosing Record Group 14, from the website’s list leads to another instructive webpage:1

RG-14

Records of the Department of Internal Affairs

Interesting site! This particular department of the state government handled all sorts of matters of value to history researchers, including

- Activities of the Surveyor General and the Bureau of Land Records (Oh, wow! We have to explore these, once we resolve our current problem!)

- Supervision of business organizations and charitable groups. (Hmhh. Might this collection have something on that trade union embroglio in the other town we’re studying?)

- Operation of a Bureau of Mines and a Bureau of Topograhic and Geologic Survey (Maps! Locations of obscure sites we haven’t been able to identify!)

- Aaah! A Bureau of Statistics, whose holdings include

- Record of Marriages, 1885–1891. (4 volumes, 1 box) {#14.25}

- Register of Physicians in Pennsylvania, 1885–1889. (3 volumes) {#14.38}

- Registration Record of Practitioners of Medicine and Surgery, 1881-1889. (1 volume) {#14.27}

All three of these series in the Bureau of Statistics offer interesting prospects for research, given that our person of interest was a doctor, but the first seems to be the rabbit we’re chasing. Same time frame. Same title that appears as the header of our page 450. Same “14.25” that appears in the parts of the URL we lopped off to get us to this page. Yes, this entry refers broadly to four volumes, when we need a specific identity for one volume. Still, that one-line description also offers us three links where we’re likely to find more details.

[Description] [Holdings] [Images]

Deeper into the Rabbit Hole

The “Description” link does lead to a page with a bit more data, but also to a record set that might not hold what we seek.

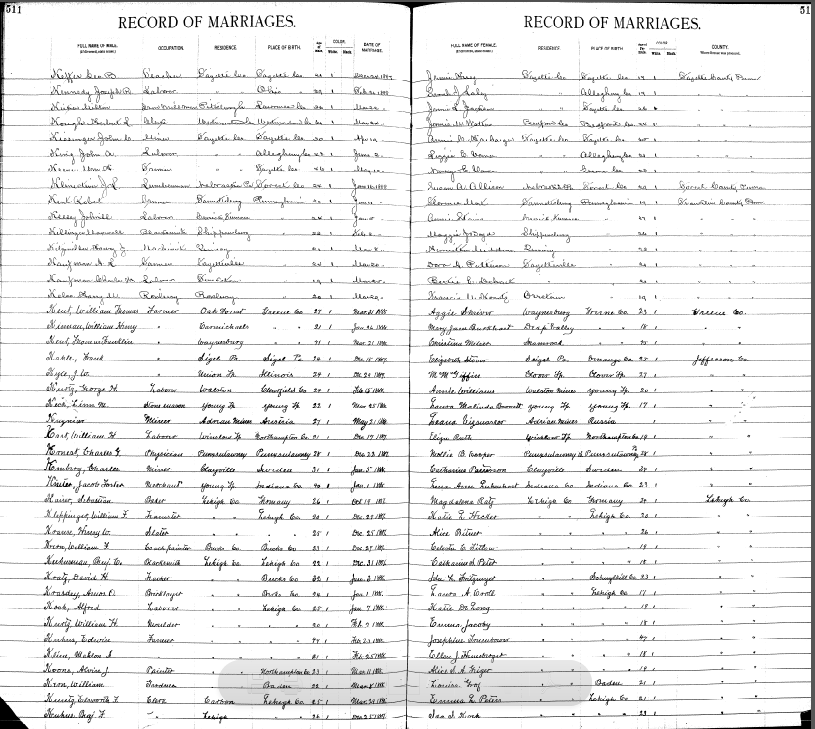

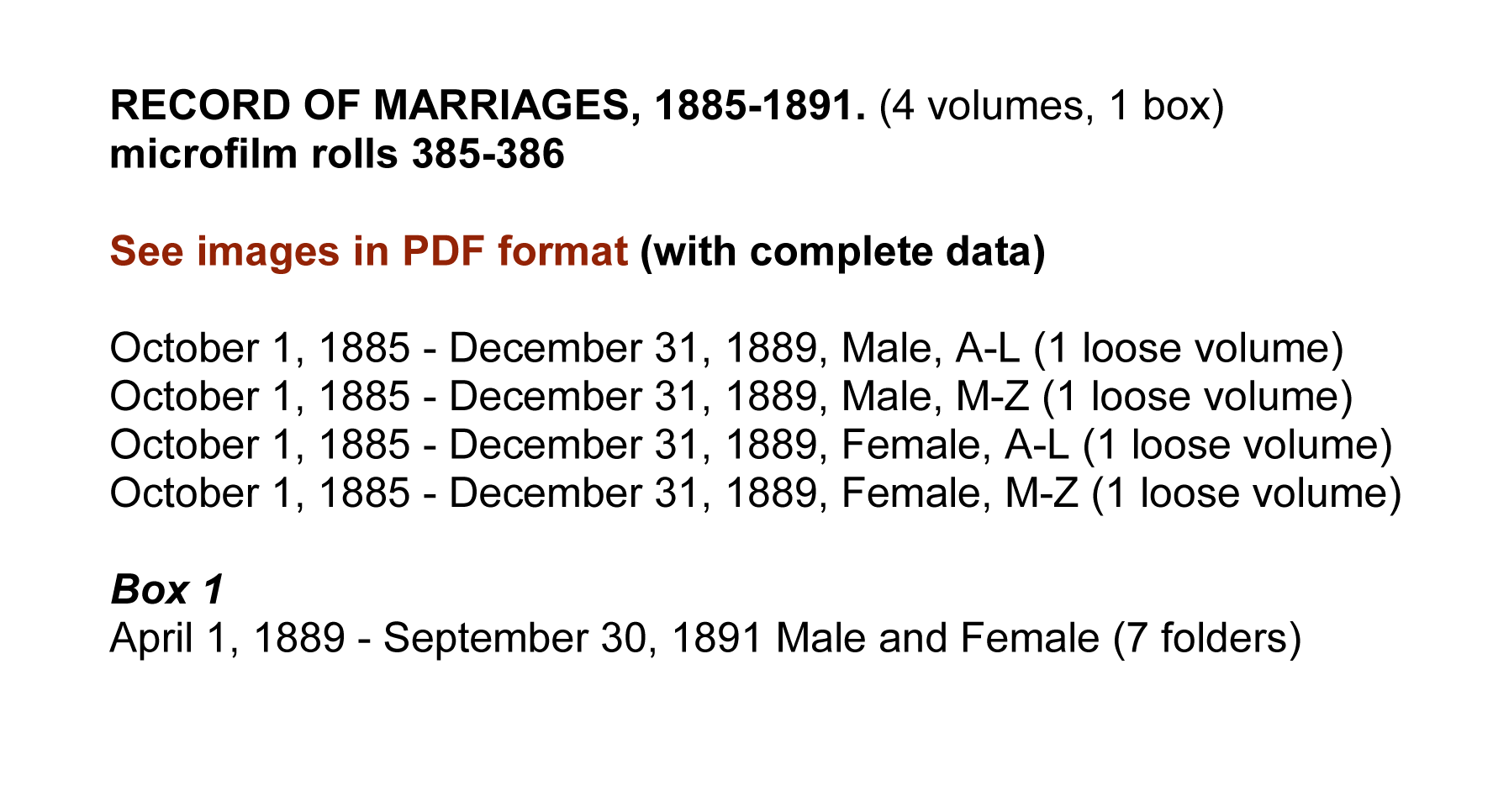

Surname of bride? Our image clearly presents its entries by surname of groom. Is this—or is this not—the source we’re chasing? Clicking on our second link [Holdings] leads to a yet another description, this one called a "container list," with differing detail:

Ah, males! Obviously, that Description page we accessed a moment ago errs in its description. The series actually includes two sets of registers—not just one for brides but also one for grooms. From the data on this page, we can tentatively identify the exact volume in which our image should appear:

October 1, 1885 - December 31, 1889, Male, M-Z

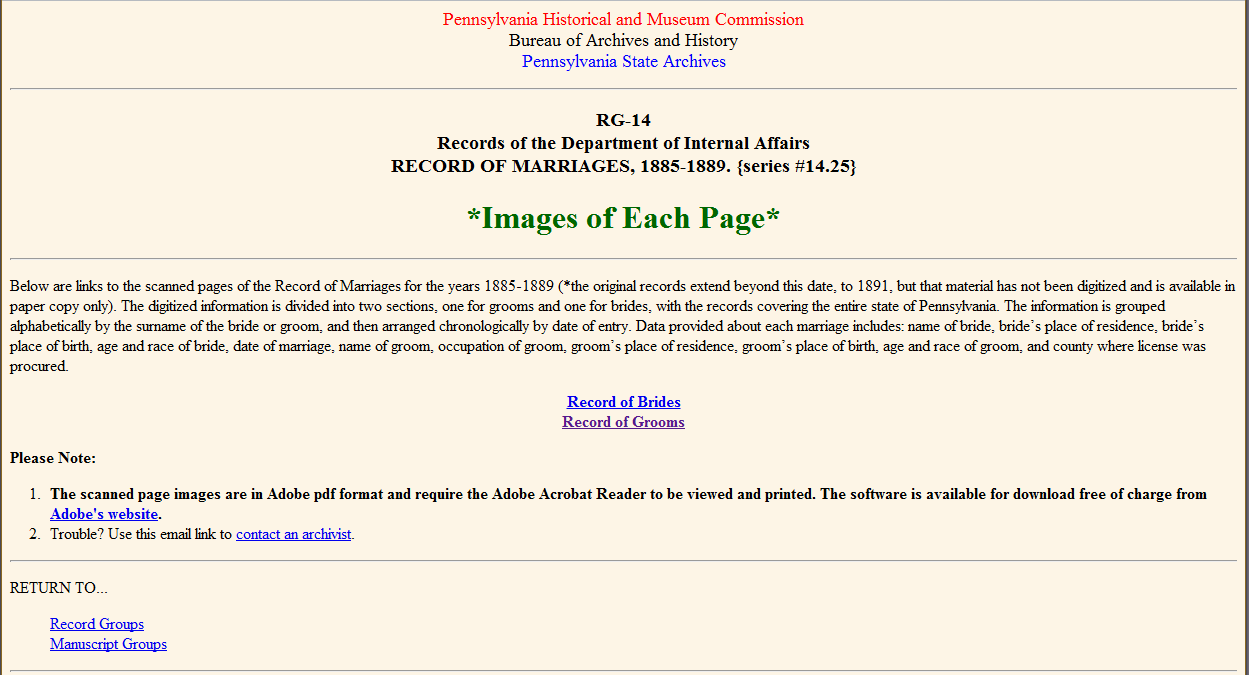

We also have a new link to follow, that highlighted phrase "See images in PDF format," which leads to yet more choices:

Two other pieces of valuable information pop up here:

- Records cover the entire state of Pennsylvania, with no exceptions noted.

- The 1885–1890 time frame does not represent all that’s available.The collection extends to 1891; the last year has not been digitized and is available in paper copy only.

The page also offers two options:

Record of Brides ♦ Record of Grooms

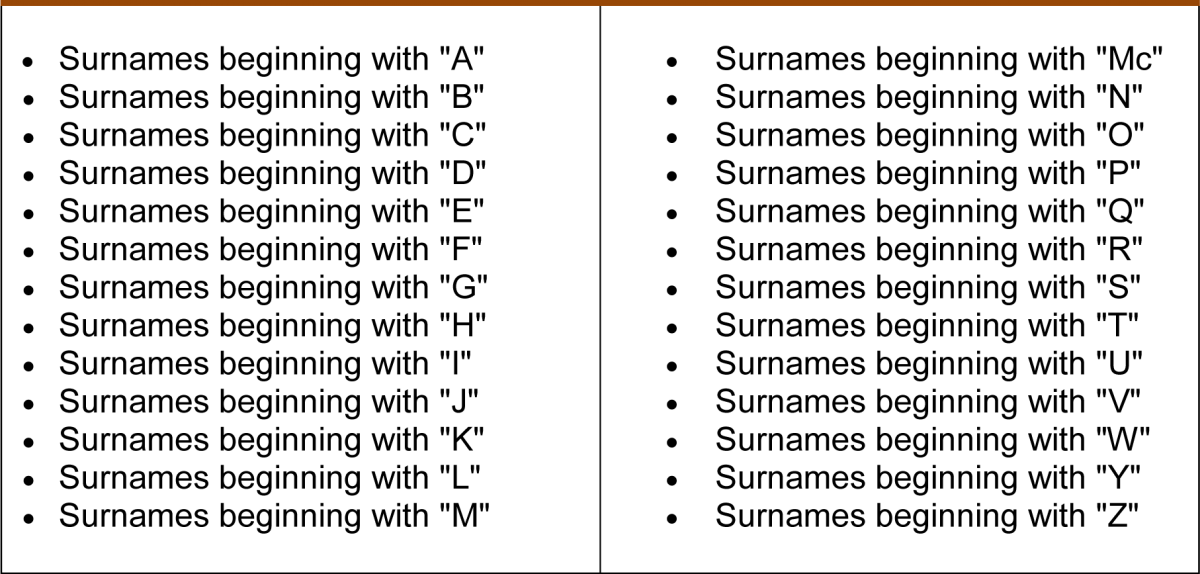

Pursuing "Grooms" led us further down our rabbit hole to another set of choices:1

Here again, the relevant letter of the alphabet led to another menu:

Pennsylvania GROOMS (1885-1889) whose surname begins with "T"2

Note: Page numbers below do not correspond exactly to page numbers on images

This time, we’re offered a choice of 11 pages, along with a warning that ought to be flagged in red: Page numbers … do not correspond … to page numbers of images.” Exclamation point! The record we started with appeared on p. 450. That certainly doesn’t fall within the proffered pages 1–11. Testing each link, we can easily enough match our record to “page” 5 on this list.

Identifying Our Rabbit—er, Record

Having snared our record, we’re back to our original question: How do we identify it? We have a register page that still needs citing. We’ve accumulated at least eight web pages. We now have two separate pagination systems that number the page itself. Out of all this, what do we use? What do we pass over as non-essential?

Digitized records that we find online typically have at least two layers. The first layer identifies the critter we’ve snared—i.e., the original record whose image we are eyeballing. The second layer identifies the snare itself: the website where we found the record. A third layer might also be needed: additional details to explain quirks in the record or the site. A useful citation will include at least the first two if not all three layers—and, of course, we'll be careful not to mix essentials for one layer into our identification of the other.

In this case, the focus of our biography is Dr. William H. Tassell, a 30-year-old first-generation-born American, living in Elk County, Pennsylvania. Having managed to rise from farm laborer to physician in just six years,3 he returned to his parental home in Potter County to marry a spinster six years his junior. Using what we have learned amid the twists and turns of our rabbit hole, we can now cite this record reliably.

Layer 1: The Record

The citation for the document itself is simple. We follow the basic format for any local or state record book—i.e.: Creator, "Book Title," page, item of interest; collection, record group; archive, location.

Pennsylvania Bureau of Vital Records, “Record of Marriages, October 1, 1885–December 31, 1889, Male, L–Z,” p. 511 (double-page spread), Tassell–Stearns, Potter County, 1886; Series 25, Record Group 14 (Department of Internal Affairs), Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg;

Layer 2: The Website

Here, too, we use a basic format. Following the premise that a website is a publication, the standard pattern for published sources applies to our website—i.e.: Creator, Website Title (place of publication : date).

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania State Archives (http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r14-25RecordMarriages/r14-25RecordMarriagesMale%20539.pdf : 17 September 2012).

The citation could easily end at this point. We simply combine the two layers to produce the following:

Pennsylvania Bureau of Vital Records, “Record of Marriages, October 1, 1885–December 31, 1889, Male, L–Z,” p. 511 (double-page spread), Tassell–Stearns, Potter County, 1886; Series 25, Record Group 14 (Department of Internal Affairs), Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg; online images accessible at Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania State Archives (http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r14-25RecordMarriages/r14-25RecordMarriagesMale%20539.pdf).

Layer 3: Discussion of the Site

If this is the only citation we have to this website, we may not want or need to discuss the manner in which the website subdivides each register into separate interfaces for brides, grooms, and each letter of the alphabet thereunder—or explain how the “page” numbers that appear on the interface aren’t the actual page numbers for the register itself. All this may be a rabbit’s nest we’d like to forget.

If, however, we are using the website extensively for a number of records, we would make future searches easier by recording an explanation of the twists and turns we have just sorted out. When we eventually publish our work, we might choose to include this explanation for the benefit of others. Or our editors might prune it and simply cite the two basic layers. In either case, here in our data-collection stage, most careful users do prefer to record details that help to use each set of records.

For explanations of this sort, no canned models apply. A practical discussion for our working files, in this case, might say:

No master index exists to this set of images. To facilitate browsing, the website offers numerous interfaces for drilling down to images within this set of registers. For example: “RG-14 … Record of Marriages, 1885–1889. {series #14.25}, Images of Each Page” (http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r14-25RecordMarriages/r14-25MainInterface.htm) offers hotlinks to the registers for brides or grooms. Thereunder, new interfaces exist for each letter of the alphabet, followed by a list of “page” numbers. Note, however, the “page” numbers provided as hotlinks are image numbers used by that interface. They do not represent the actual page number in the original register.

The Bottom Line

We all want research to be simple. We love online records because they are so handy. Yet technology offers an endless variety of platforms and websites constructed in endless wayas. As a result, those easy-to-find online sources are typically much harder to identify, in a meaningful way, than the original records would have been.

Newer researchers think of “source identification” in terms of how do I cite this? The underlying issue, however, is not how to cite. It is, instead:

- how to analyze a record, or record set, so we understand what we are using;

- how to dissect a confusing organizational system;

- how to connect a random record to the collection that identifies it;

- how to reassemble scattered details to define exactly what we have, what is essential, and what path one must take to relocate it.

By strengthening these skills, we give ourselves the ability to create sound citations for any kind of problematic source.

More importantly, in developing these skills, we come to appreciate the time we’ve spent defining exactly what kind of source we’re using. In that process, we will have learned details that enable us to assess the trustworthiness of the record. We will have discovered new resources we never knew existed, like those physician registers we can now search for more information about our Dr. Tassell.

This level of study also exposes problems within the source from which we have extracted data. In this case, tracking that record image to its source revealed multiple errors in that one entry for our couple—starting with a wrong identification of the county in which they wed. Never mind that their marriage is officially recorded in the State of Pennsylvania’s master register of marriages between 1885 and 1891; errors do happen every time records are copied and new indexes are created. But the nest of problems involved in their story is one we’ll save for later. This present rabbit hole has been dug deep enough for now.

1. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Pennsylvania State Archives (http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r14-25RecordMarriages/r14-25GroomSurnameInterface.htm : 22 September 2012).

2. Ibid. (http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/bah/dam/rg/di/r14-25RecordMarriages/r14-25-T-GroomInterface.htm : 22 September 2012).

3. 1880 U.S. census, Potter County, Pennsylvania, Hebron, E.D. 104, p. 5, dwelling 49, family 51; accessed at Ancestry.com (http:.//www.ancestry.com : 22 June 2012); citing National Archives microfilm publication T9, roll not stated, digitized from Family History Library microfilm 1255165, page 464A.

How to Cite This Lesson

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 12: Chasing an Online Record into Its Rabbit Hole,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-12-chasing-online-record-its-rabbit-hole : [access date]).