Every researcher has heard this advice: To prove a point, we need multiple sources—multiple sources, independently created. Not multiple sources that all copy each other. Decades ago, we were told that we needed "three sources that agree." In recent years, that "instruction" has been streamlined. Supposedly now, all we need are two.

If that’s been your guidance, forget it. Life doesn't operate by a simple rule we can mindlessly follow. There’s no magic number. What’s needed is thorough research and logical thinking.

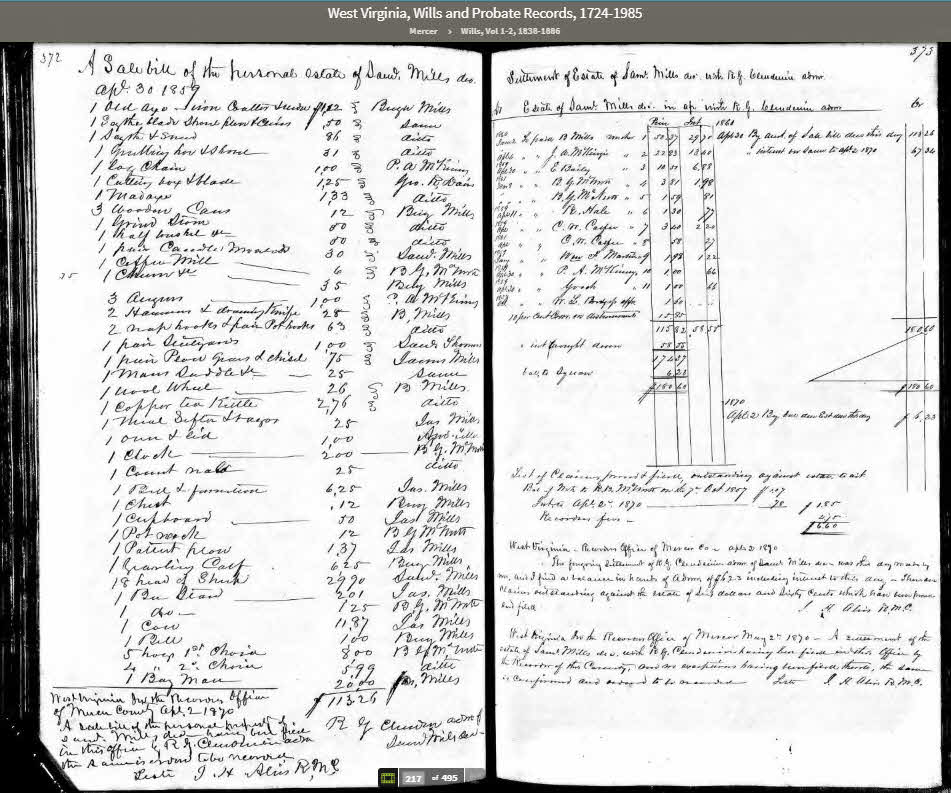

Samuel Mills of Mercer County, West Virginia, makes that point. Online, we can find a kajillion assertions that he died on 30 April 1859. Most don’t bother to identify evidence for the claim, but the claim can easily be traced back to the record we’ve attached to this post. It begins:

Fantastic! The document states his death date in plain black and white.

No. It doesn’t.

The Need for Logical Thinking

When a legal document is created and a date is added, that date is there for a purpose. With documents legally recorded in courthouse registers, we typically find two dates—at least two dates—the date the document was created and the date the document was filed.

This particular document, the one recorded on the left-hand page, is an account of the estate sale held to liquidate Mills's property and divide proceeds among the heirs. In the lower corner of that page, we see a notation that the document was filed on 2 April 1870. But the filing date was not the creation date. That leaves us with the still-unanswered question: When did the administrator hold this sale that he’s now reporting to the court?

In chorus, let’s all repeat: When a legal document is created and a date is added, that date is there for a purpose.

Why does this document need a date and what would it need?

An estate settlement involves several documents, or many documents, each generated by an event. Each event had a specific purpose. The most basic ones are these

- A petition to open the estate or file the will

- Appointment of administrator or executor, which may have triggered the signing of a bond

- Inventory of estate

- Account of probate sale

- Final account of income, expenses, and distribution among heirs

If a probate record requires someone to supply the date of death, which record would logically carry that date?

The logical place would be the petition to open the estate or file the will. That’s the event for which proof of death would be needed. (Unfortunately, the date of death was often not recorded on that document, but that’s a different tale of woe.)

Meanwhile: When the estate is sold, what date is essential to that process and that event? The date of the sale.

All this is logic. Now let’s talk about the need for thorough research—which is a simpler way of saying “multiple sources, independently created.”

The Need for Other Evidence

Will: Samuel Mills left a will. It’s recorded in the same register with the sale bill for his personal property. It’s clearly dated 15 December 1858. Below the recorded transcript, in that courthouse register, we see:

Legal note penned by Deputy Clerk of Court: “At a monthly Court held for the County of Mercer at the Court House thereof, on Thursday, the 7th day of April 1859, The last Will and Testament of Samuel Mills Sr. deceased was proved according to law. … Certificate is granted to the said Robert G. Clendenon for obtaining letters of administration. …”2

Pension Application: Samuel Mills’s widow outlived him. In 1878 she filed for a pension on the basis of his service during the War of 1812. That required proof of his death. Two documents in that file address the issue of his death date:

Affidavit of Widow: “She was married to said Samuel Mills under the name of Nancy Rinehart on the ___ day of ____ 1833 by William Garretson at his [Garretson’s] residence, … her husband died about 1858 in the County of Mercer and she has never intermarried since.”3 The blanks are there in the affidavit.

Affidavit of Witness: “R. G. Clendenin a witness of lawful age, being Sworn says that he was well acquainted with Saml Mills a Soldier of the War of 1812 who lived and died in the County and State (then Virginia) aforesaid in my immediate neighbourhood about the commencement of the year 1859. I administered on his estate in April 1859.”4

In short:

- 15 December 1858, Samuel wrote his will but did not name an executor

- “About 1858” he died, according to the widow whose memory for important dates in her life was clearly fuzzy

- “About the commencement of the year 1859” he died, according to his administrator

- "April 1859," the estate was administered, according to the administrator

- 7 April 1859, the will was proved and letters of administration issued, according to the court clerk

No. Samuel did not die 30 April 1859. The imaged document carries that date. The date even appears immediately after the word "Decd." But it is not telling us that he died on that date.

30 April 1859 is the date of the estate sale. The record was created for the purpose of documenting that sale, the income it generated. That’s the event for which a date was needed. The date of Samuel's death was not relevant to the purpose for which that document was created.

When we find a document that seems to give us an easy answer to a burning question, we don't just grab it and run with it. The reliable reaction is a two-stage process:

- First, we need to think about the purpose of the document and what it is actually telling us.

- Then we need to do thorough research to find all the evidence that bears upon that that question.

1. Mercer Co., WV, Will Book 1: 372; imaged in “West Virginia, Wills and Probate Records, 1724–1985,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 14 October 2019) > Mercer > Wills, Vol. 1-2, 1838–1886 > image 217 of 495.

2. Mercer Co., WV, Will Book 1: 87; imaged in “West Virginia, Wills and Probate Records, 1724–1985,” image 72 of 495.

3. Nancy Mills, widow’s pension application, service of Samuel Mills (Pvt., Johnston’s Co., Va. Militia, War of 1812), application 31152, certificate 33868; imaged in “War of 1812 Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files,” database with images, Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/image/322481910 : 14 October 2019), 73 images; for the widow’s affidavit, see image 322481976. Italics added for emphasis.

4. Ibid., affidavit of R. G. Clendenin, 18 June 1884, image 322481972. Italics added for emphasis.

HOW TO CITE:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, "Having a Record That Says Something Doesn't Prove It," blog post, QuickTips: The Blog @ Evidence Explained.com (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/quicktips/having-a-record-that-says-something-doesnt-prove-it : posted 15 October 2019).

Thank you for this excellent…

Thank you for this excellent example of thorough research. My mother was very good at this and I am trying to learn to follow in her footsteps as a sister and I work to build upon her decades of family tree building.

Key Word - Think

Thank you for this excellent article. The most significant word I noted was "think." And that is something we sometimes forget to do. I am new to genealogy research so I really appreciate your insights.