Lawrence of Arabia is said to have said, “All records lie.” If so, then how do we, as researchers, discover where the truth likely lies?

We do that through two habits:

Thorough research. The logic here is simple: We cannot piece together a puzzle if we have only a few of the pieces.

Thorough analysis.This tack is a tougher one—especially for those working in the area of historical biography. Thorough analysis has to go considerably beyond a consideration of the evidence that deals with our person of interest. We also have to

- consider the totality of each record in which that person appears. We analyze the data on our person against the data for all others, to define patterns and situations that aren’t explicitly stated. (See QuickLesson 2 for the distinction between the information a source provides and the evidence we draw from that information.)

- place each record into contemporary context, studying the historical and legal backdrop for the stage on which each person and each record played a role.

CASE AT POINT

Meet William Cooksey (Cuksey, Cucksey, Coocsey, Cooksee, Cooksie, Coxy, &c)

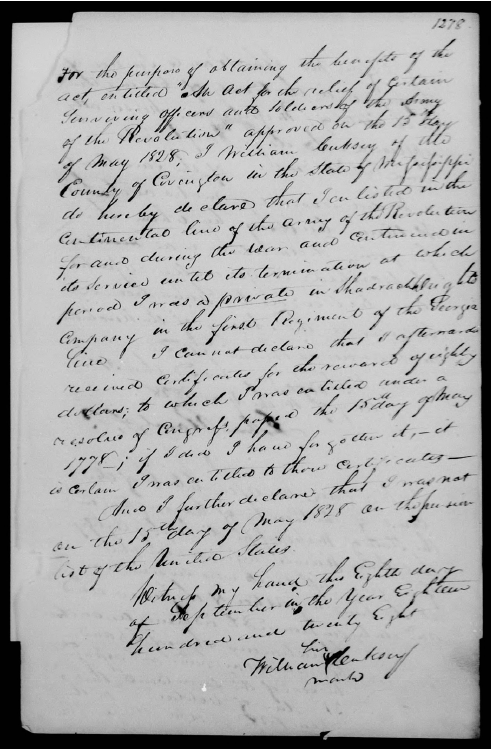

A Revolutionary War soldier named William Cooksey offers a case at point. As an aged man, in 1828, he lived in Covington County, Mississippi. There, he engaged a lawyer to file a pension application for him.

In his affidavit, Cooksey swore three things:

- He had been a private in Shadrack Wright’s Company of the First Georgia Regiment, Continental Line.

- He did not receive the cash bounty promised to Continental soldiers under a Congressional act passed 15 May 1778.

- He was not on the U.S. pension rolls.

Cooksey gave no other details about his service. He made no effort to explain why he did not receive the cash bounty to which he seemed entitled. He also X’d that petition, implying that he was illiterate or in such ill health that he could not sign his name. In response to his petition, the U.S. Pension Office reported that it could find no record of his service and invited him to submit further evidence. In that interval, however, he died.1

Cooksey did, indeed, serve in Georgia’s Continental Line. Today, a search of standard military records housed at the National Archives—and digitized online—quickly turns up a Compiled Service Record under one of the many variant spellings of his surname.

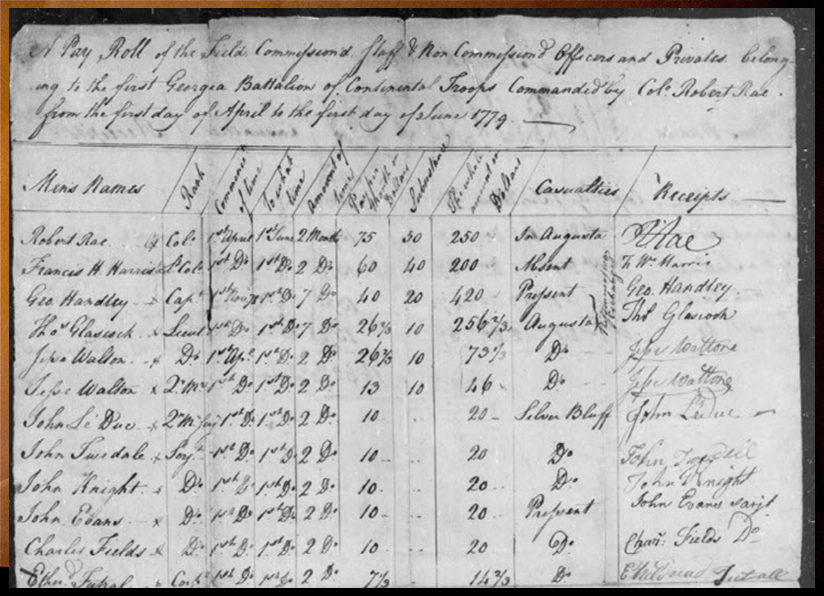

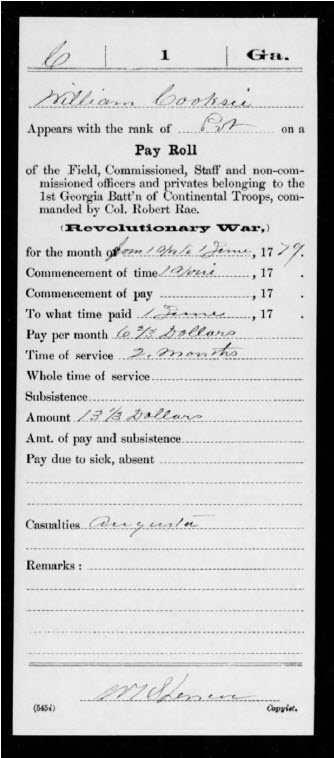

Cooksey’s Compiled Service Record (CSR)

Three service cards briefly chronicle Cooksey’s service. (See sample card below) From these, researchers deduced that

- he enlisted on 1 April 1779 and served until 1 July of that year;

- he was at Augusta, Georgia, on 1 June 1779 when he was named on a payroll;

- he was, at that time, a “casualty,” but the record does not state the nature of his “casualty” or the conflict in which it occurred; and

- he was furloughed before the 1 July pay date—likely due to the seriousness of his injuries.

His CSR cards also verify that he served in the 1st Georgia Battalion, but they makes no mention of Shadrack Wright or the 8th Company of the Georgia Line for which Wright was a captain.2

Biographers who stop their research at this point are left with a seriously flawed picture of Cooksey’s role in the Revolutionary War.

The CSRs are official documents. Each is an original creation. Nonetheless, each man’s file is a derivative source. The CSR project, which embraced all wars through the Philippine Insurrection, was begun nearly a half-century after Cooksey’s death. The War Department, “to permit more rapid and efficient checking of military and medical records in connection with claims for pension and other veterans’ benefits,” combed its trove of military rolls and created “summaries” of the service of each identifiable veteran of conflicts between the Revolutionary War and 1903.3

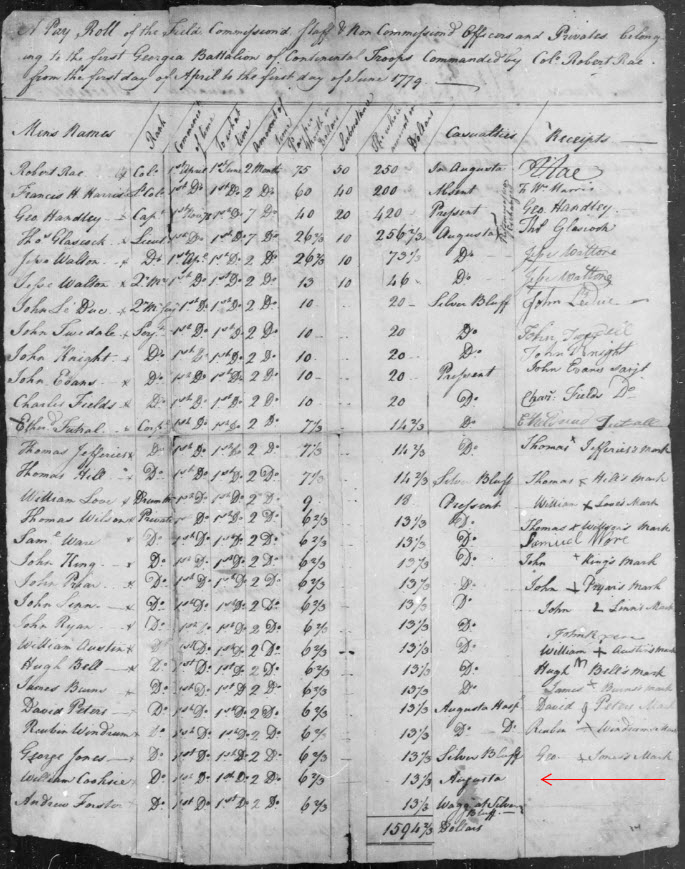

Original Payrolls

The original payrolls, once located, provide significant other data.4 (See sample card, below.) When we consider the function served by these rolls, it is clear that William Cooksey and his comrades enlisted prior to the 1 April 1779 date shown on this roll. When the structure of the payrolls is analyzed, it is obvious that Cooksey was not at all a casualty. When Cooksey’s information is placed into legal context, we see a likely explanation as to why he did not file for that federal bounty at the end of the war. This more accurate interpretation of his service then equips us to extend our research into a broader associational and historical study of Georgia’s participation in the Revolutionary conflict. From that, we can identify the battles in which Cooksey likely fought as a soldier of the Continental Line and significantly expand our biography of this backcountry yeoman.

Consideration 1: The function of the rolls

Military payrolls were not created to document dates of enlistment or discharge. They cover exactly what their name implies. The start date and the end date on each of Cooksey’s service cards represent payroll periods. With each new payroll, the date of the last payroll became the start date for the new roll. When military and veteran records are studied for all of William’s identified compatriots, it is clear that all enlisted for service well before the 1 April 1779 start date of the surviving rolls. Given that pattern, it is also likely that William enlisted well before that date also.

Consideration 2: The structure of the rolls

The CSR’s attribution of “casualties” to William is an error—a significant misrepresentation of the original document. No evidence exists that he was ever injured or fell ill as a result of his service. As we can see from both the 1 June and 1 July payrolls, the “casualties” column was used by his commanding officer to report status information for each man. All men carry an entry in this column, but none were actual casualties. All we can draw from the entries in the “Casualties” column of both rolls is that (1) Cooksey was in or near Augusta on 1 June; and (2) he was on furlough when the 1 July roll was drafted.

Consideration 3: Legal Perspective

William’s pension application refers to two Congressional laws. An examination of those laws enables us to more accurately interpret his records and his service.

15 May 1778

This act of the Continental Congress provided “That every non-commissioned military officer and soldier, who hath inlisted, or shall inlist, into the service of these states for and during the war, and shall continue therein to the end thereof, shall be entitled to receive the further reward of eighty dollars at the expiration of the war.”5

15 May 1828

The relevant portion of this act, which prompted William to file for his pension, stipulated “That every surviving non-commissioned officer, musician, or private, in said army, who enlisted therein for and during the war, and continued in service until its termination, and thereby became entitled to receive a reward of eighty dollars, under a resolve of Congress, passed May fifteenth, seventeen hundred and seventy-eight, shall be entitled to receive his full monthly pay in said service, … to begin on the third day of March, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-six and to continue during his natural life.”6

One point is obvious from both laws: In order to qualify for the eighty dollar bounty, Cooksey would have had to serve in the Continental forces until the war ended. The surviving payrolls document his service only through 1 July 1779. The war would continue for another two years and more. Together, these facts raise the possibility that he did not receive the “reward” because he did not complete the service.

Consideration 4: Associational & Historical Context

Service prior to 1 April 1779

A review of Georgia’s role in the Revolution clarifies another issue. The period covered by these two payrolls represent a lull in military action in and around Augusta, where Cooksey was said to be on 1 June. The 1 April–1 June period of the first payroll was essentially one of regrouping after several North Georgia battles that occurred in February and March 1779, particularly those of Kettle Creek and Briar Creek.7 In the wake of those battles, men deserted rather than enlisted. William’s presence in the April–June period suggests that he likely joined in the buildup to those conflicts, not after them—a conclusion reinforced by the accounts that compatriots later related in their own pension applications.

Service in June 1779

From the 1 June payroll we can also draw indirect evidence that is not stated or even implied on Cooksey’s CSR. Only five men on that roll are said to be at Augusta. By studying the service records of the other four men, we identify them as the brigade commander (Col. Robert Rae), his second-major, a captain, and a lieutenant. Nothing states directly why one lowly private had accompanied these four officers to Augusta, North Georgia’s principal crossing point into South Carolina, or what their mission was. Nineteen days later, however, a “detachment” of men from the First Georgia regiment, led by Col. Rae, was among the forces at the Battle of Stono Ferry, outside Charleston.8

Service after June 1779

The 1 July notation that Cooksey was on furlough—a privilege granted to only one other soldier—implies that his leave was given in the wake of the Battle of Stono Ferry. The collection of payrolls used by the War Department for its CSRs has no other roll for Col. Rae’s First Battalion until November 1779. The roll of that date makes no mention of Cooksey, implying that his service had ended. However, a surviving muster roll dated 1 August 1779, a document not used for Cooksey’s CSR, cites “William Coucksie” as a private in Rae’s forces, along with the notation “deserted.”9

In tandem, the known records suggest that Cooksey did not return to Continental service after his furlough. That desertion and failure to serve out the course of the war would explain his non-receipt of the eighty-dollar bounty to which he referred in his pension application.

Other Service

The Continental Line was not the only force in which able-bodied patriots served during the Revolution. In colonial and pre–Civil War America, all able-bodied males, within ages specified by the legislature of each colony or state, faced mandatory duty in local, county-based militia. Additionally, Georgia was one of the colonies that, at least for some while, maintained a minuteman force of men who agreed to “serve on a minute’s notice.” A broader study of Georgia’s Revolutionary era materials yields a “certificate of service” issued in 1785 by the militia and minuteman commander Col. Elijah Clarke, in which he identifies thirty-two men who served under him, including “William Cucksey.”10 Subsequently, on 28 April of that year, the state of Georgia issued a bounty land warrant to “William Cucksey, Minute Man.”11

Our Bottom Line

As historical biographers, if we probe no further than the standard service cards we will miss much evidence. We will fail to discover the errors within these compilations. Ultimately, the conclusions we reach about events, circumstances, or people will be at the least confused—and, at worst, radically wrong.12

1. Affidavit of William Cuksey, 31 October 1828, William Cuksey/Cucksey (Pvt., Shadrack Wright’s Co., 1st Regt., Ga. Cont’l. Line), pension application 1278; digital images, Ancestry.com's Fold3 (http://www.fold3.com : downloaded 30 August 2008), images 14750445–14750457; imaged from Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives microfilm publication M804 [roll number not cited at Fold3; should be 707]; at the time this document was downloaded, Fold3 was known as Footnote.com. The post-1862 widow’s application that is included in this file has been erroneously connected to him by the War Department or the National Archives. Other problems evident from this file are not being covered, in order to keep this QuickLesson at a reasonable length.

2. “William Cooksie” (Pvt., 1st Geo. Batt., Revolutionary War); digital images in “Revolutionary War Service Records,” database, Ancestry.com's Fold3 (http://www.fold3.com : accessed 30 August 2010), images 17080038, 17080042, 17080046; imaged from Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army during the American Revolution, National Archives microfilm publication M881 [roll number not cited; likely roll 396]. For the identification of Wright’s company in which Cooksey would have served, see Francis Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution (Washington, D. C.: Rare Book Publishing Co., 1914), 100; and Lucian Lamar Knight, Georgia’s Roster of the Revolution (Atlanta, Ga.: Index Printing Co., 1920), 9–10.

3. Anne Bruner Eales and Robert M. Kvasnicka, Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives of the United States, 3d ed. (Washington: National Archives and Records Administration, 2000), 127. This work is an excellent guide for all historians. Its discussions of major record collections and their history go far beyond most other NARA publications, including the standard Guide to Federal Records in the National Archives of the United States, available in a 3-volume edition and online at http://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records.

4. “1 Georgia Battn. Col. Robert Rae, Maj. John Habersham, 1779–1780; 4 Pay Rolls—April 1, 1779 to Feb. 1, 1780,” image copies in “Revolutionary War Service Records,” database, Fold3 (www.fold3.com : accessed 10 September 2010), images 7661708, 7661709, 7661612, 7661716, 7661733, 7661738; imaged from Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775–1783, National Archives microfilm publication M246 [roll not stated].

5. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789,Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., vol. 11 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908), 502; digital image, Library of Congress, A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875 (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lawhome.html).

6. United States Congress, Public Statutes at Large, Richard Peters, ed., vol. 4 (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1846), 269–70, for 20th Cong., Sess. 1, Chap. LIII; digital images, A Century of Lawmaking.

7. Detailed studies of Revolutionary battles in North Georgia are rare. For a convenient chronology and overview, see “Georgia in the Revolution,” Georgia Society, Sons of the American Revolution (http://www.georgiasocietysar.org/rev1779.htm : accessed 7 January 2012). For fuller discussions of the the Battles at Kettle Creek and Briar Creek, see Robert Scott Davis, Georgians in the Revolution: At Kettle Creek (Wilkes Co.) and Burke Co. (Easley, S.C.: Southern Historical Press, 1986), particularly 11–44; and Daniel T. Elliott, Stirring up a Hornet’s Nest: The Kettle Creek Battlefield Survey, Lamar Institute Publication Series, Report No. 131 (Savannah: The Lamar Institute, 2009), 37; PDF online (http://shapiro.anthro.uga.edu/Lamar/images/PDFs/publication _131.pdf : accessed 7 January 2012).

8. “Stono Ferry,” The American Revolution in South Carolina (http://www.carolana.com/SC/Revolution/revolution_stono_ferry.html : accessed 4 November 2010).

9. “Georgia Militia and Continental Regiments of Infantry,” Marquis de Lafayette Chapter, Sons of the American Revolution (http://www.lafayettesar.org/gamilitia.htm : accessed 4 September 2010), for “A Muster Roll of the 1st Georgia Battalion of Continental Troops Commanded by Col. Robert Rae, August, August the 2nd 1779.” Neither the original of this document nor an image copy has yet been located; however, the data that it provides on soldiers and officers has proved consistent with other records on those men.

10. Grace Gillam Davidson, Lelia Thornton Gentry, et al., Historical Collections of the Georgia Chapters Daughter of the American Revolution (1929; reprinted Baltimore, MD: Clearfield, 1995), 172. The original document from which this typescript was made has not yet been located, but its content is consistent with auxiliary records.

11. Lloyd DeWitt Bockstruck, Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants Awarded by State Governments (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1996), 127. The original record represented by this abstract has been ordered but not yet received; in the meanwhile, its content is consistent with auxiliary records.

12. For a 109-page summation of what is proved, unproved, and disproved for the life of this William Cooksey, see Elizabeth Shown Mills, "William Cooksey (ca. 1745–1829): Research Notes, 30 January 2014; archived at Elizabeth Shown Mills, Historic Pathways (http://www.HistoricPathways.com) under the "Research" tab.

How to cite this lesson:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 3: Flawed Records,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-3-flawed-records : [access date]).