Biographical research on people from the past is a gamble. Our person of interest may or may not have been literate. Even the schooled may have left few traces of their existence. Many documents we expect to find for the place and time will have suffered destruction. The answers we seek to specific research questions may not appear in any surviving record created by our person.1

All these trials explain why many successful researchers live by the FAN Principle: When those we study left no document to handily supply the information we seek, we often find it in the records created by members of their FAN Club—their Friends, Associates, and Neighbors.

Case at Point: Mary Smith

Identifying someone of common name, distinguishing them from other same-name people, is always a challenge. Identifying a female of common name, from an era in which women lived domestic lives sheltered from the public eye, can seem impossible. It’s not—not if we apply that FAN Principle.

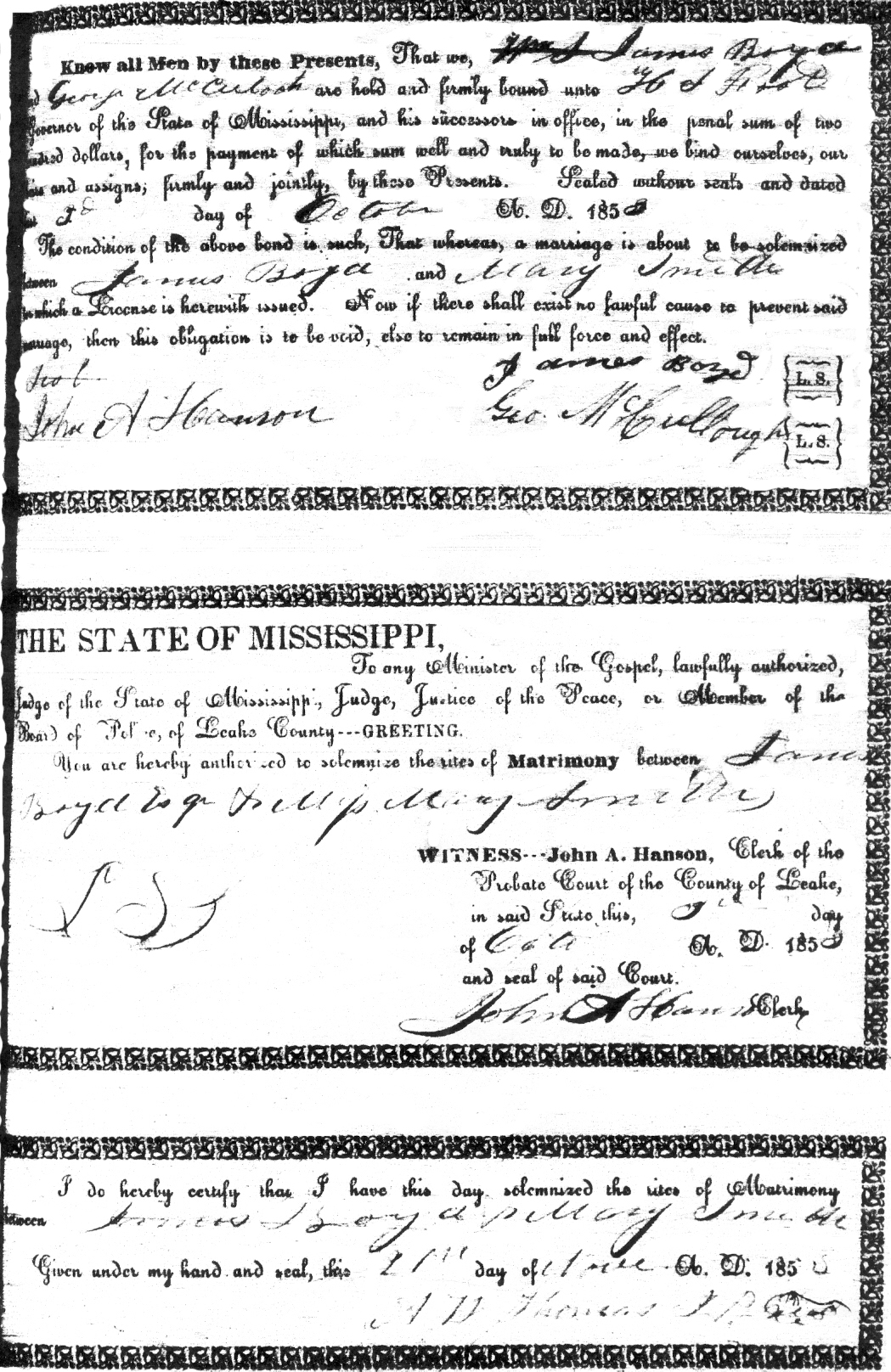

In 1850, there were at least 17,995 females in the U.S. named Mary Smith.2 One of them appears on a marriage record, three years later, in the rural county of Leake, in the hills of Mississippi. She married a young widower named James Boyd, another common name under which three marriage licenses were issued that same year in that one rural county. One of those is the springboard for this lesson.3

The license, bond, and return for Mary and James tell us nothing about James’s new wife, aside from the name Mary Smith. We are given no age, no parental identities. Typically, useful clues lie in the identity of the men who cosigned the marriage bond and officiated at the ceremony. In this case, the bondsman was James’s cousin, George McCullough. The official was a justice of the peace named A. W. Thomas.

So, who was this Mary Smith? At this point, only one certainty existed: She belonged to James Boyd’s FAN Club. She and her family should be findable among his friends, associates, and neighbors.

Clues from Context

Social and economic context also help us narrow the field of potential candidates. Leake was a rural county and Mary’s new husband was a farmer—which suggests he did not go far to go courting. Yeoman farmers began their days before sunup and worked until dark. They took no vacations, or even weekends off. When rain left fields too muddy to work, the cows still had to be milked at dawn and dusk. Chickens had to be fed. Hogs had to be slopped. And this particular farmer, in search of a wife, was also a new widower with five children—the youngest a babe in arms.4

All things considered, the Mary Smith who married James Boyd likely lived within two to three miles of him—five at the most. Five country miles in a modern pickup truck is a five-minute sprint. In any search for Smiths in the 1850s, it would have been a big territory to cover: a five-mile radius encircling James would encompass some eighty-eight square miles.

Analysis and Planning

Designing a research strategy calls for identifying all known resources and correlating them against the work previously done.5 The census taken of Leake County three years earlier provided at least seven candidates for Mary. Others arrived after that. Prior researchers had followed the paper trails left by all contemporary Smiths in Leake County. They found no wills, probates, deeds, court cases, church registers, newspapers, or other local records to identify the family to which she belonged.

One resource remained unexamined, a kind of courthouse record that exists widely across nineteenth-century America. The agency that created it carried different names in different places: commissioners court, board of supervisors, police court, police jury, or whatever name was used by the local board that handled administrative matters such as poorhouses, licenses and tariffs, elections, and road maintenance. The minutes kept by those bodies are also a historical resource frequently neglected by researchers because the original clerks rarely indexed them.

Aside from poorhouse matters, the activities chronicled in this record set were activities that rarely involved females. Nonetheless, these minutes could be critical to determining Mary Smith’s identity, because of the premise that governed this research project: Clues to the identity of a female will come from the FAN Club of the man she married. Theoretically, the activities uncovered for James Boyd—once we read those minutes year by year, page by page, and line by line—would point to Mary’s identity. They did not disappoint us.

James Boyd’s FAN Club

Four months after Mary married James, the Leake County Police Court held its spring meeting and issued a rash of road orders, including this one:

“Ordered that Robt. Cheshire be appointed Overseer of the Road from Haysville to Bennett’s Ferry, with authority to work the following hands on said Road … John Bennett, Franklin Boyd, James Boyd, Saml Smith, Wm. Smith, Joseph Smith, Andrew Boyd, Wm. B. Shepherd, Wm. Robinson, F. T. Hanson’s hands, Duncan Fulton’s hands, James Fulton, Joseph Owens, B. N. Day, Wilson Milner.”6

Here, we have a neighborhood. Road orders of that era typically assigned men to work the roads on which they lived, usually a two-to-three-mile stretch. Not all men who lived along a road were expected to do road duty. Men past poll-tax age, roughly in their fifties or older, were rarely assigned that physical labor; instead, their community service was likely to be jury duty, poll watching, and the inventorying of estates. Crew assignments also rotated. One year, the work would fall to menfolk from one set of families; the next year, the responsibilities would shift to others.

The takeaway from this court order is clear: Four months after James Boyd married Mary Smith, he and his known brothers Franklin and Andrew shared a two-to-three-mile stretch of road with three young men named Smith.

Curious, but perhaps coincidental, is the arrangement of the names in the road order. Clerk John A. Hanson placed the three Smiths into the midst of the Boyd family. Indeed, immediately after citing Franklin Boyd and then his next-youngest brother James, the clerk switched to the Smiths, before returning to the youngest Boyd brother, Andrew. Was Hanson (himself a member of F.T. Hanson's FAN Club) following the actual arrangement of houses along that road? Or did his arrangement of names reflect his mental associations, amid which he jumped from James Boyd—the new husband of Mary Smith—to the Smith males, before realizing that he had not cited the youngest Boyd?

As always, theories need to be tested.

Researching the FAN Club

Each new “find” we make calls for a reevaluation of resources and strategies. In this case, the identification of James’s FAN Club dictates research on each member of that road crew.

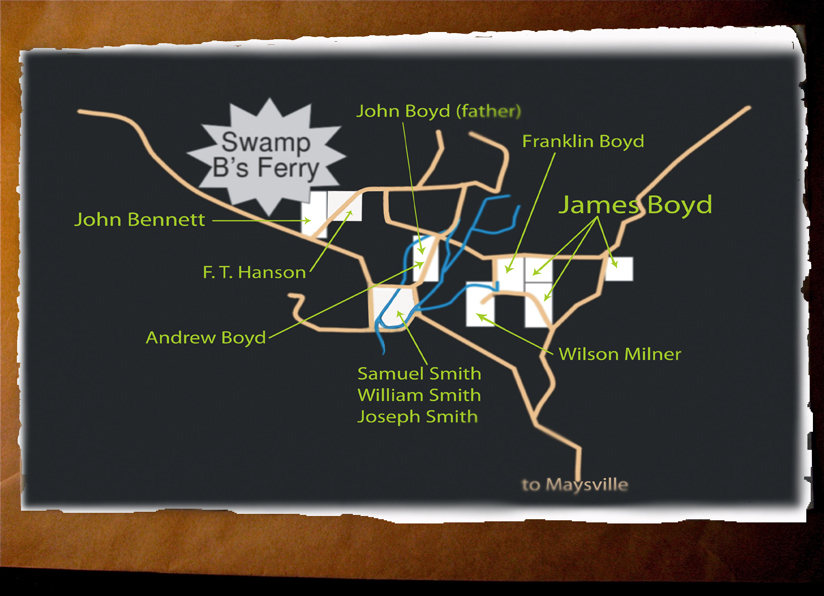

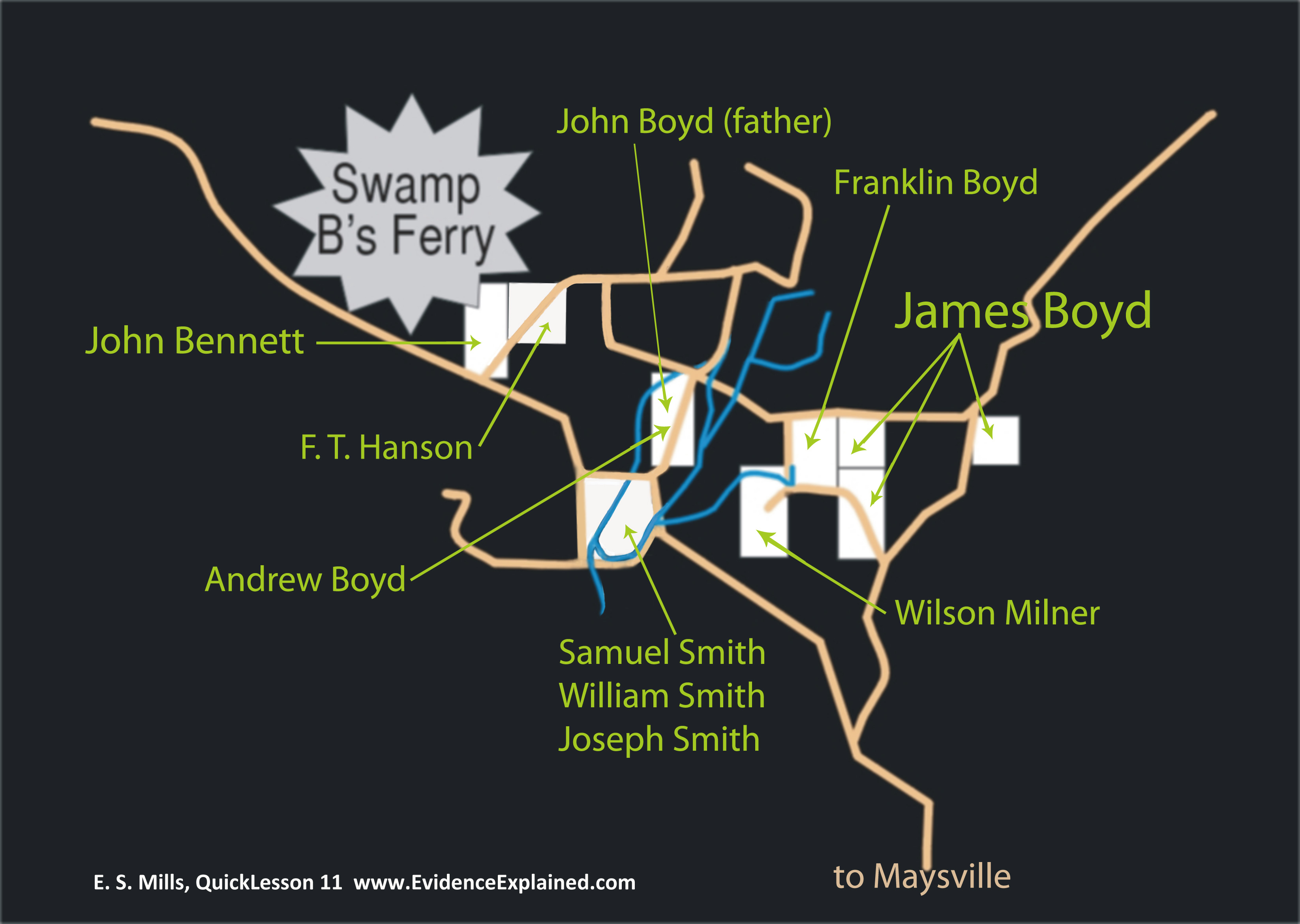

Research in the local deeds and the federal land records for the county identified their landholdings. By platting the lands, we could create a visual of the neighborhood, with the relative position of each man and his family

Moving clockwise from about ten o’clock on this neighborhood sketch (click to enlarge), we find:

- John Bennett of Bennett’s Ferry.7

- John Boyd, who does not appear on the crew list because he was too old, but was the father of all the young adult Boyds.8

- Franklin Boyd, residing on part of the land he had bought the year before from his financially over-extended brother James.9

- James Boyd, newly wed to Mary Smith, and still residing on one of the tracts he had sold to Franklin.10

- Wilson Milner, who had been enumerated next door to James on the 1850 census.11

- Samuel, William, and Joseph Smith—a cluster for which we have only one Smith landowner in this neighborhood: William.12

- Andrew Boyd, James’s still-landless brother, who apparently resided in the parental home.13

- Fielding T. Hanson, aka F. T. Hanson of the road order.14

Finding Mary

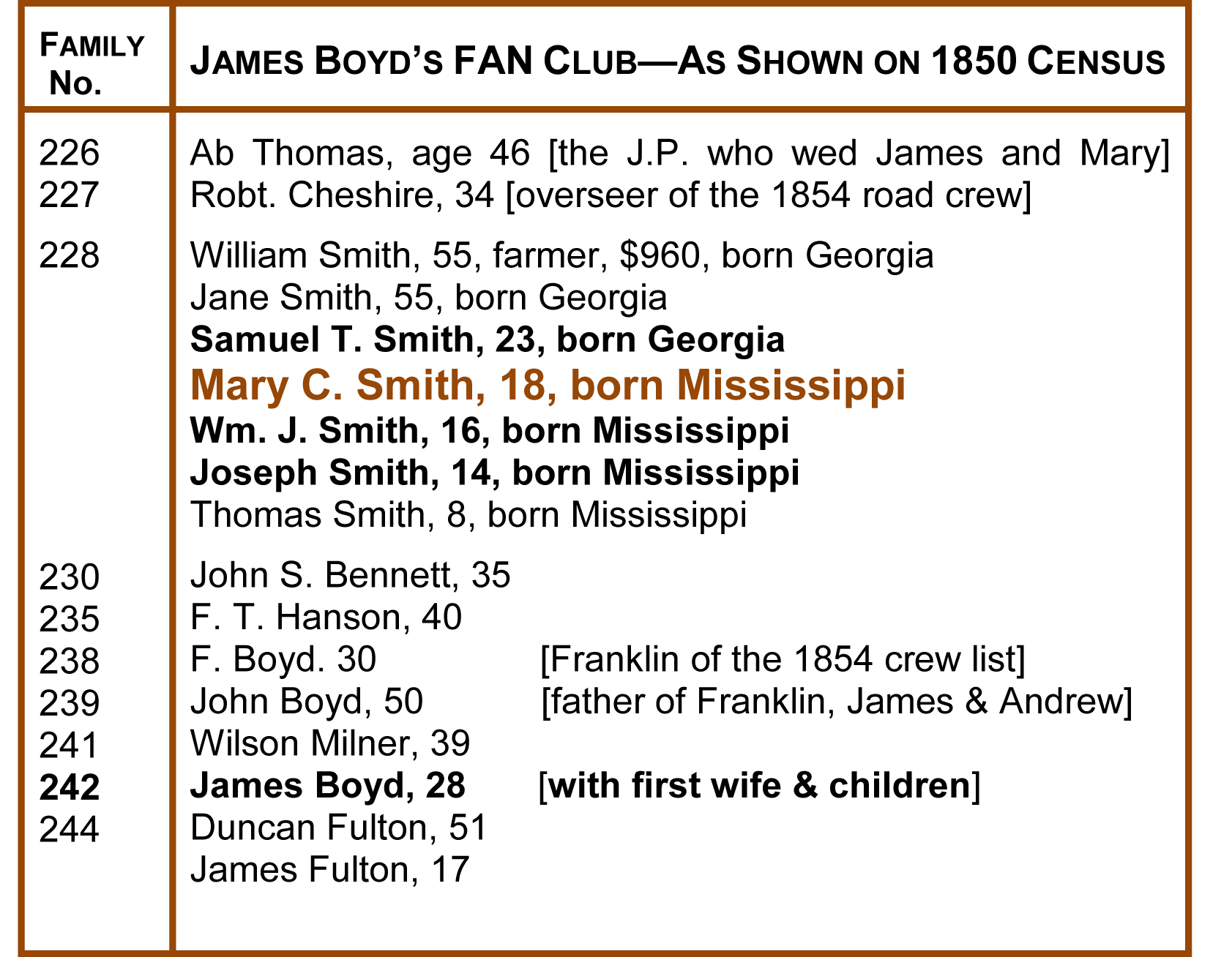

The location of the land of this William Smith, within a mile of James Boyd, suggests a likely birth family for Mary. The question then became: Did this Smith family have a daughter Mary of marriageable age in 1854? The 1850 census of that Bennett’s Ferry neighborhood confirms our hypothesis:

Here, in family 228, we have not only an unmarried Mary of marriagable age, but the whole cluster of Smiths from the 1854 road crew, itemized in the same sequence (oldest to youngest) in which they were listed on the road order.15 Two doors from this family, at 226, we find Ab Thomas, the justice of the peace who officiated at Mary’s marriage to James—the same Absalom W. Thomas from whom William Smith, Wilson Milner, and later Andrew Boyd all bought the land on which they built their farms.

James Boyd’s FAN Club, as we expected, were Mary Smith’s “friends, associates, and neighbors” as well. It would be nice, after all of this, to think that James and Mary lived happily ever after. They didn’t, but that story involves another knot of problems to untangle in a later lesson.

The Bottom Line

The evidences we use to reconstruct human lives—all too frequently—are not outright statements of “fact.” For want of those ideal documents, handily left to us by diligent scribes, successful researchers learn to harvest clues. Bits and shards of evidence that prove nothing by themselves can be immensely valuable as pointers to other records or as fragments we can assemble to build a case for whatever question we seek to answer.

1. Drawn from Elizabeth Shown Mills, QuickSheet: The Historical Biographer’s Guide to Cluster Research (the FAN Principle) (Baltimore: GPC, 2012).

2. “1850 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: 25 August 2012), query for “Mary Smith.” There were undoubtedly many others enumerated on returns where the census marshal used only initials.

3. Leake Co., Miss., Marriage Book B, pp. 43 (James M. Boyd and Caroline Kenady, license: 18 March 1853, marriage: 20 March 1853), 72 (James Boyd and Mary Smith, license: 3 October 1853, marriage: 21 November 1853), and 77 (James Boyd and Mary P. Ward, license, 23 November 1853, no return). Although James's marriage license identified him as "James Boyd, Esq.," he was neither an attorney nor a justice, the two categories of professionals who were commonly called "esquire" in this period. The county clerk, John A. Hanson, called most men "Esq." on the marriage licenses he issued in this era.

4. The 1850 census (among other records) identifies the oldest four children of James Boyd and his first wife Elmira. His last child, Martha Elmira Boyd, was born 10 August 1853, amid a yellow fever epidemic that took the life of James’s mother Mary (Warren) Boyd and then, apparently, James’s wife. Both James and his father John remarried in November 1853.

For Martha Elmira’s birthdate see Harmony Cemetery (3319 Spanish Bluff Road, Nacogdoches, Texas), Martha E. Scarborough tombstone. For the death of James’s mother on 4 June 1853, see Warren-Vaughn-Ellison Bible [exact title of Bible unknown], published 1846 by Harper and Brothers, New York; owned 1990 by Yandel S. “Pete” Warren of Benton, Miss.; extractions of family data made in 1990 by Patsy Robinson of Richland, Miss.; published as “Warren-Vaughn-Ellison Bible,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 78 (March 1990), 55–56. For the remarriage of James’s father in the same month that James married Mary Smith, see Leake Co., Miss., Marriage Book C, p. 38. Also see 1850 U.S. Census, Leake Co., Miss., population schedule, Beat 2, p. 17-B (stamped), p. 33 (penned), dwelling 216, family 239 (John Boyd family), and dwell. 219, fam. 242 (James Boyd family).

5. For additional guidance in the analysis and planning of research, see Elizabeth Shown Mills, QuickSheet: The Historical Biographer’s Guide to Individual Problem Analysis (Baltimore: GPC, 2012).

6. Leake Co, Miss., Police Court Minutes, Vol. B (1844–1862), p. 185, March Term 1854.

7. The Bennett family owned extensive lands around the ferry. For John, see particularly U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (http://www.glorecords.blm.gov : accessed 6 December 2008), doc. 19302, accession no. MS01210_.201, “State Volume Patents," John Bennett, 80.54 acres described as W½ NW¼ S36 T12N R6E.

8. For John’s location, see Leake Co. Deed Book I, p. 219, Samuel Joslin Jr. to John Boyd, 21 February 1843,sale for $300.00, of 80 acres on the waters of Yockanokana River near the road leading from Carthage to Bennett’s Ferry, legally identified as W½ of SE¼ S31 T12N R7E.

9. For Franklin’s land, see Leake Co. Deed Book J, p. 301, James Boyd and wife Elmira to Franklin Boyd, 29 January 1852 sale for $423, four tracts of land described as (1) SW¼ of SW¼ S32 T12N R7E, (2) S½ of E½ of SE¼ S31 T12N R7E, which James purchased from the U.S. Land Office via patent issued 1 October 1851; (3) part of the W½ of N¼ S5 T11N R7E, which James purchased from Sewal Brown and wife Caroline L. in 1850; and (4) 6.5 acres described as N end of NE½ of NE¼ S6 T11 R7E. James would remain on part of the land, after the sale, until his removal from the county later in 1854. Also see Deed Book K:325, by which Franklin Boyd, on 4 May 1854, purchased from Duncan Fulton of the road-crew list, 40 adjacent acres described as SE¼ SW¼ S32 T12N R7E.

10. Leake Co. Deed Book I, p. 290, Sewal and Caroline L. Brown, by Francis Burnett, agent, 29 November 1850, to James Boyd for $65, 80 acres described as W½ of NW¼ S5 T11N R7E.

11. For Milner’s land, see Leake Co. Deed Book H, pp. 365–66, Absalom W. Thomas and wife Elizabeth to Wilson “Millner,” 11 January 1848, sale of 80 acres described as W½ of NE¼ of S6 T11 R7E.

12. For Smith’s land, see Leake Co. Deed Book H, p. 113, Absalom W. Thomas and wife Elizabeth to William Smith, 15 December 1846, 160 acres described as NE¼ of S1 T11N R6E.

13. Andrew appears not to have left the parental home until early 1856, when he bought 40 acres from Absalom Thomas, the J.P. who officiated at the Boyd-Smith marriages; see Leake Co. Deed Book M, p. 66.

14. For Hanson’s land, see Leake Co., Miss., Deed Book I, p. 373, Richard Minshew and wife Sarah to F. T. Hanson, sale for $120, 40 acres identified as NE¼ of NW¼ S36 T12N R6E.

15. Also note the age of the father William Smith. At 55 in 1850, 59 in 1854, he would not be the William who was assigned to the road crew. That William would have been the son “Wm. J.,” age 20 in 1854. Similarly, Duncan Fulton, age 54 at the time of the road order, was not required to serve; but, because he was a slaveowner, the 1854 commissioners ordered him to provide “hands,” along with his son James, who would have been 21 at the time of the order.

Posted: 26 August 2012

How to Cite This Lesson

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 11: Identity Problems & the FAN Principle,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-11-identity-problems-fan-principle : [access date]).