9 February 2019

On 14 August 1814, British forces set fire to the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and other government buildings in the nation's new capitol. Out of crisis came opportunity for those of us who study the past, albeit an opportunity that is often overlooked.

That fire destroyed not just buildings but records the federal government needed for its day-to-day operations—and records that American citizens needed to secure payment for services and goods they had rendered, for pensions they had earned, for lands they had owned prior to the time the U.S. government took over their swath of the frontier.

That crisis spurred Congress to action. Well, nudged might be a better word. In the usual fashion for Congress, it spent 17 years debating how serious the issue really was and how it might best be dealt with.

Eventually, on 2 March 1831, Congress decreed that the most important records of our government should be published for preservation—not only those created by Congress but also those documenting actions of the executive-branch departments, bureaus, agencies, and commissions. The result has been hundreds of thousands of volumes of published reports, journals, digest, codes, and miscellaneous documents typeset and dispatched to libraries across the country—records that help to document the troubles of many obscure Americans.

Several thousand of these volumes have been digitized and are accessible online in the Library of Congress's American Memory-American Law module. Even more are available across the country at more than 1,250 university and metropolitan libraries that have been designated Federal Depository Libraries. Some subscription-based providers of digitized records—most notably, ProQuest Library Edition and HeritageQuest—offer even more convenient access.

If you are not already conducting research in these materials, explore this link. Discover the richness of the records. Explore EE's Chapter 13. It will introduce you to many other record types under the umbrella "published government documents"—and demonstrate how to cite them, as well. Then visit the FDL library nearest you for endless more possibilities.

And for those of you who love history's mysteries, and the challenge of using a document as a stepping stone to finding the story behind the record, we offer a sample here.

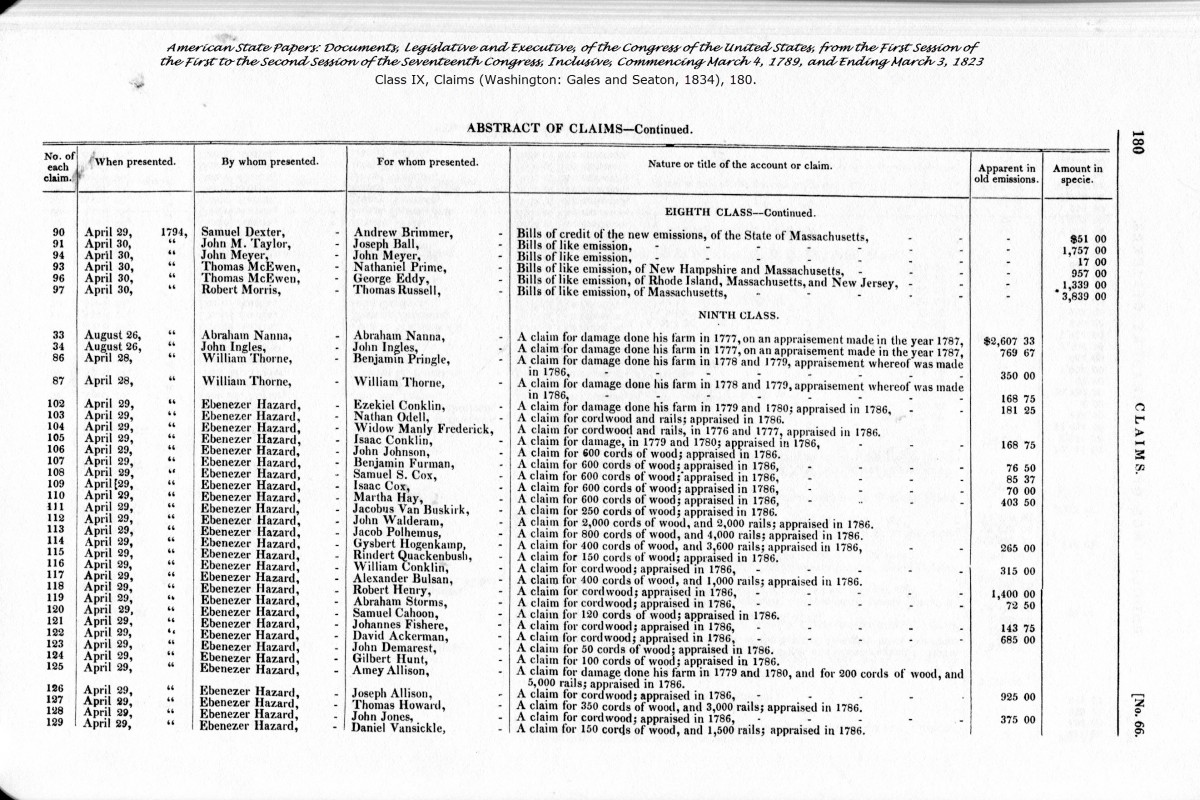

Look at the four consecutive entries for "A claim for damage done his farm in 1777 ... on an appraisement made in the year ...." The wording and the consecutive nature of the records imply a connection, even though there is some variation in date. If you were doing biographical research on a man who bears the name of one of these claimants, how would you proceed to discover

- Whether this is your person-of-interest?

- What trauma occurred on his farm to cause the damage?

- Whether the activity on his farm was a part of a bigger affair that involved the other three men and their farms?

- What effect did these traumas have on each family?

- Did the U.S. government acknowledge responsibility? Did it pay the damages claimed?

- What other records might exist in other departments of government that would give you more details about this event and its aftermath?

PHOTO CREDITS: "File:BritishBurnTheCapitol-CoxMural.jpg," Wikimedia Commons (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BritishBurnTheCapitol-CoxMural.jpg : accessed 9 February 2015), public domain image; citing "British Burn the Capitol, 1814, a painting by Allyn Cox in the Hall of Capitols, a corridor in the House side of the United States Capital."