14 January 2014

Problem:

You are tracing a freedman in post-bellum Louisiana, one Louis Bellow. A fellow researcher has sent you this image, reporting it to be the marriage record of your person-of-interest. Being a careful researcher, your colleague has documented the record quite well—almost as EE would do it:

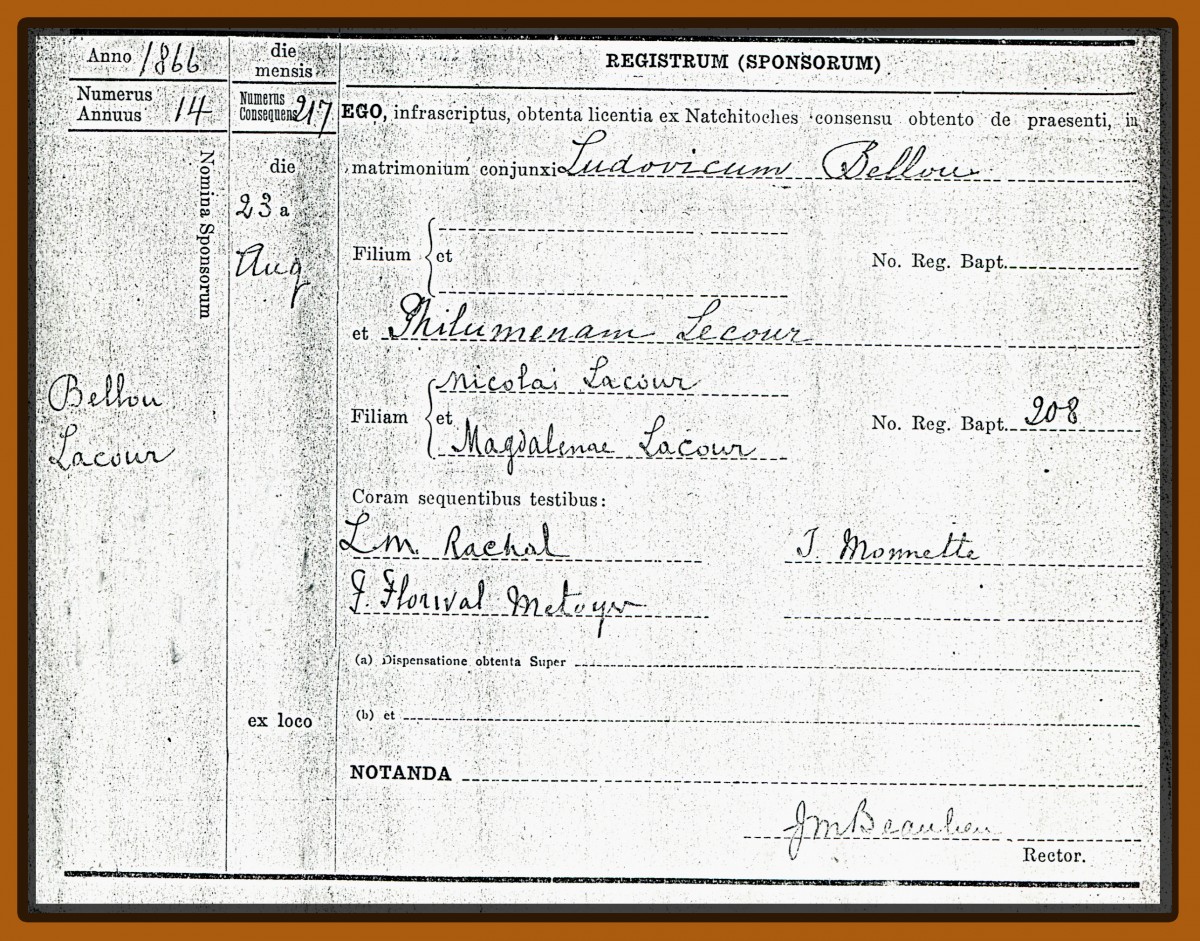

St. John the Baptiste Catholic Church (Cloutierville, La.), “Registrum Matrimoniorum Omnium quae sunt Contracta in Ecclesia St. Joannis Baptistae, et Missionibus, in Oppido Cloutierville, Louisiana, Diocesis Alexandriae (Certified 1915),” p. 108, entry 217, marriage of Louis Bellow and Philomene Lecour, 23 August 1866.

Never mind that the record is in Latin. You can still figure out the basic facts. Are you bummed because no parents are named for the groom? Ecstatic to have the parents of the bride identified—that being the tougher challenge for researchers? As you analyze the record, what thoughts come to mind? What would you do next, on the basis of this information?

POST-SCRIPT: 9p.m., 14 January 2014

Janis, RootsJockey, Yvette, and Sheila have offered a superb riff of ideas in today’s comments. EE won’t try to outdo them. What we will do here is give you some “final answers” from which you can see

- just how astute all their suggestions have been; and

- why this kind of analysis is needed for every document, no matter how simple it seems to be.

Original or Derivative?

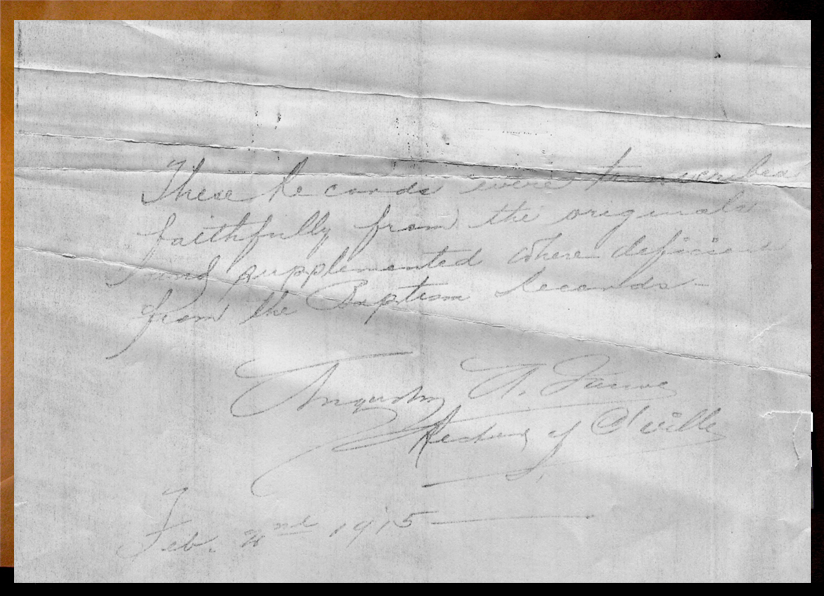

The most critical issue is triggered by the pair of words “certified 1915.” Whether we’re dealing with church records or civil ones from the courthouse of town hall, registers that carry a certification are often transcriptions, not the original. RootsJockey caught this immediately and suggested an effort to view the original. Yvette also noticed that this register looked “too neat to be from 1866.” Both were right on the money. EE would now plan two “first steps,” with subsequent actions based on the results of these two.

1.

Verify exactly what the priest said in his certification of 1915. Pursuing that, we find that the priest penciled his certification in the front of the register. It’s barely legible now. Here’s the image:

Undoubtedly, you’ve caught the two main points:

- “transcribed faithfully from the original” and

- “supplemented where deficient from the Baptismal Records.”

That word supplemented obviously explains why the Latin version gives parental data for the bride but not for the groom. It also raises another issue: Could the 1915 copyist validly assume that the bride’s record would be in his particular set of church books? In EE’s opinion: No, non, nulla!

2.

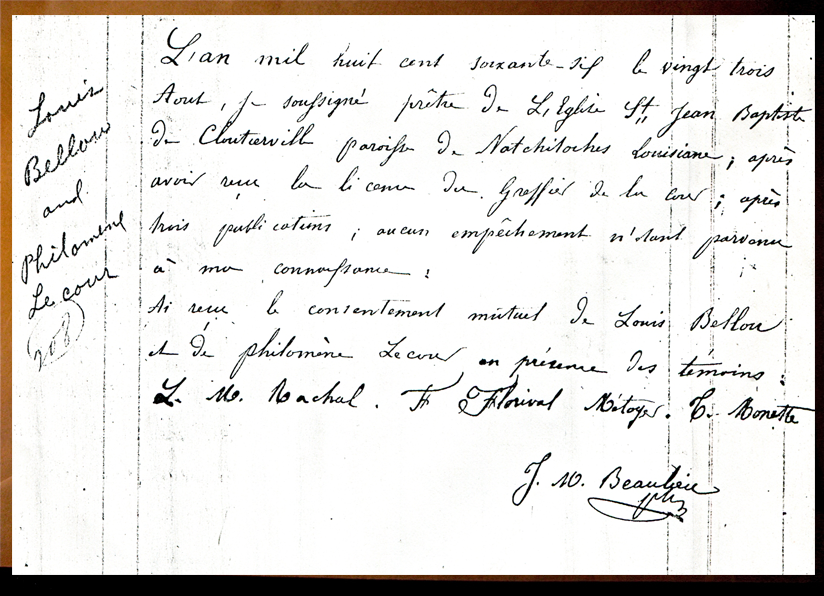

Seek a copy of the original. Done. It’s a French-language record:

Translation:

In the year eighteen hundred and sixty-six, the twenty-third of August, I the undersigned priest of the Church of St. Jean Baptiste de Cloutierville, parish [county] of Natchitoches, Louisiana, after having received [from the couple] the license of the clerk of court, after three publications without any impediment having come to my knowledge, I have received the mutual consent of Louis Bellow and of Philomène Lecour, in presence of the witnesses L. M. Rachal, F. Florival Métoyer, T. Monette. [signed] J. M. Beaulieu, Priest.

Hmhh. No reference to the parents of either spouse. However, thanks to the “certification” note, we have an inkling where the parental data came from for Philomene—that assertion that she was the daughter of Nicolas LaCour and his wife Madeleine.

This triggers Step 3: find the original baptism—and that exposed a whole new set of problems:

Problem 1. The Latin certificate gives us an entry number, but the original baptismal volume does not use that numbering system. The number corresponds to the new, nicely written, nicely indexed, Latin-language baptismal books that were also “helpfully” created in 1915. Using the date from that record, it was easy enough to find the original record. In fact, incredibly for that area, it was in English:

On the 19th of February 1848, I the undersigned, have baptized Philumine, legitimate daughter of Nicola Lacour and of Madaline Lacour, born the 29th September 1847. Godparents were Evariste Lacour and Mary Rosa Layssard.[1]

Oops! Steps 4, 5, and 6 (census work, a search for other children in the Cloutierville records, and a courthouse survey) revealed just how deep the new problems were:

Problem 2. The Lacours and their Layssard inlaws were all residents of the civil parish of Rapides, not Natchitoches. The LaCour couple were not part of the Cloutierville congregation and had no other children baptized there. The baptism of this child was recorded at Cloutierville only because a circuit-riding priest recorded it in the first church he came to after he stopped at their plantation and performed the baptism.

Problem 3. The Lacours and Layssards were white. The Bellow family—as you would assume from our initial description of the problem—was not.[2] In 1866, a legal marriage between the races was not possible in Louisiana. What’s more, the Lacours and Layssards were quite wealthy and quite prominent; the Bellow couple would spend their life in relative poverty. That gives us problems of both “race” and “class.” No, despite what the church books say, Louis Bellow did not marry a daughter of Nicolas and Madaline Lacour.

Problem 4. The baptized Philomene Lacour was born in 1847 and the marriage record is dated 1866. Her age fits—so long as we’re simply guessing at how old a bride ought to be. However, both subsequent censuses on which Philomene (Lecour) Bellow appears consistently make her 10 years older—born 1838.[3]

Step 7? Well, of course, we’ll search for a Philomene Lecour (and all variants) in the 1838 period—a period in which no church even existed at Cloutierville—which means the search turns elsewhere. Of course, we’ll consider how any and all Philomenes who are closer to her age might fit into the families of the three men who served as witnesses to Philomene’s marriage. Of course, we’ll also search for the baptismal records of Philomene’s own children, identify their godparents, and see how she might fit into one of their families. And, of course, we’ll study her census neighbors just as intensely—not only in the church books but also the civil records.

In fact, we’ve already done this—and the work plan worked. But, let’s save all that for another day.

In the meanwhile, we can draw three lessons from today’s discussion question:

- There is no such thing as The Gospel According to the Church Clerk.

- Identity decisions based on “the name’s the same” or “the only one” often come back to bite us.

- We can’t do reliable research by consulting just one kind of record, as the 1915 cleric did in his efforts to determine Philomene’s identity. Church records have to be balanced against census records, which have to be balanced against legal records, which have to be balanced against the law that existed in the time and place, which has to be balanced against historical context, which ...

1. St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (Cloutierville, La.), “No. 1, Baptism of Whites from 1847 [to] 1863,” unnumbered pages and unnumbered entries, roughly in chronological order; consulted via preservation microfilm made by Northwestern State University, Natchitoches.

2. Both Louis and Philomene apparently were quite light in color, but still legally “nonwhite.” The 1870 census, taken by an Anglo, identifies them as “mulatto.” The 1880 census, taken by a Frenchman who lived some miles upriver, calls the whole family white. Louis and Philomene do not appear on the 1900 census of Natchitoches, but on that census—in which the enumerators had only the options “white” or “black”—all the census entries for their offspring call them “black.”

3. See 1870 U.S. census, Natchitoches Parish, La., pop. sch., Ward 10, p. 19 (stamped p. 446), dwell. 168, fam. 169, “Louis Bello” and wife Mary (i.e., Marie Philomene); National Archives microfilm publication M593, roll 518. Also 1880 U.S. census, pop. sch., Ward 10, ED 36, p. 37 (stamped p. 691), unnumbered households; National Archives microfilm publication T9, roll 457; the “duplicate copy” sent by the enumerator to the Bureau in D.C. copies the family surname as “Beno” rather than “Bello” but all family members carry the right forenames: Louis, Philomene, Augustin, Joseph, Ulus, Alice, and Simon and the right ages. On the 1900 census of Natchitoches Parish, most of their married offspring appear under the spelling “Billow.”

church record analysis

It appears to lead directly to Philomene's baptism record, for one thing. It offers an alternate spelling for the groom's surname (Bellou). And there's that Metoyer again!

Janis, truth is: It's hard to

Janis, truth is: It's hard to do any research at all along Louisiana's Cane River or Red River without bumping into the name Metoyer or Rachal!

Church record analysis

I would contact the diocesan archives in hopes of viewing the original marriage record and checking for potential baptismal records for children.

-rootsjockey

My analysis of the document

The first thing I notice it that it Other things I notice:

My research plan would start with:

sorry, the heading of the

sorry, the heading of the first list got garbled as I submitted, should have read "Things I notice:" I can't seem to edit the comment though.

Love this exercise by the way

Love this exercise by the way! It feels like my BCG-supplied document but *with* the ability to discuss my thoughts with others.

Sorry, nr. 4 should have read

Sorry, nr. 4 should have read "...consent was obtained FROM those present" not "BY those present." It appears that my English is even worse than my Latin tonight :-)

Great to read your analysis.

Great to read your analysis. Comparing your analysis to my own highlights one of my pitfalls: I tend to plan too far ahead. My first two steps were enough. And I should have picked up on the possibility that the transcriber/indexer "helpfully" supplemented the information. I'm glad I picked up on the major point though, that is was a derivative source and I should go back to the original. The original would have shown me that the information about the parents wasn't in there so I would have caught my omission.