Researchers love Ancestry and similar websites. Attorneys, biographers, genealogists, medical scientists, professional historians, and students all turn to them as the world’s largest shopping malls for historical records. These providers offer censuses, deeds and land grants, legal suits, medieval manorial rolls, military records, probate proceedings, prison files, vital records, and thousands of other types of materials for studying the past and reconstructing human lives.

Many researchers also love it when record providers serve up ready-made citations they can just copy-paste into their own research notes. That way (they think) they don’t have to “waste" time thinking through what they are using, how many alteration processes the image or the data has been subjected to, how reliable the original version may have been, and how less reliable a convenient derivative may be.

The many alterations and iterations that records go through before they are delivered to us online are the crux of the problems we face in citing online history sources. Some citation guides recommend identifying only the site name and sponsor, the URL, and the date visited.1 That approach satisfies one function of a citation: identifying where to go to find the information again. It also assumes the website does not die, the material is not pulled from the site, or the site does not change its architecture so that the link is no longer workable.

Evidence-style citations to websites also addresses two other needs:

- the need to locate that information elsewhere, should the material become inaccessible online.

- the need to identify our source material clearly enough that readers can make at least a cursory evaluation of its reliability—and so that we, when our thorough research turns up conflicts between our sources, can reevaluate each of them and seek better records as needed.

This QuickLesson builds upon QuickLesson 25. That lesson broadly discusses ARKS, PALs, paths and waypoints, data-location conventions used by various web publishers. Here, we focus on one publisher—the one that generates the most questions in EE's forums. It uses one record, presented by a thoughtful reader with more questions than we could address in a forum posting. Using that one quite-common source-type and the accompanying source data provided by Ancestry, this lesson illustrates how to think through the issues and create a citation that clearly identifies what we are using.

Ancestry’s Source Identification

As perhaps the world’s largest commercial purveyor of historical records, Ancestry does what all good providers do. For every database and every collection of images, it provides us with some descriptive details about the source from which it took the extracted data or image. Sometimes, that background information is far less than we want. Typically, it is far more than what is wanted by those who prefer a clean and lean citation they can copy and paste.

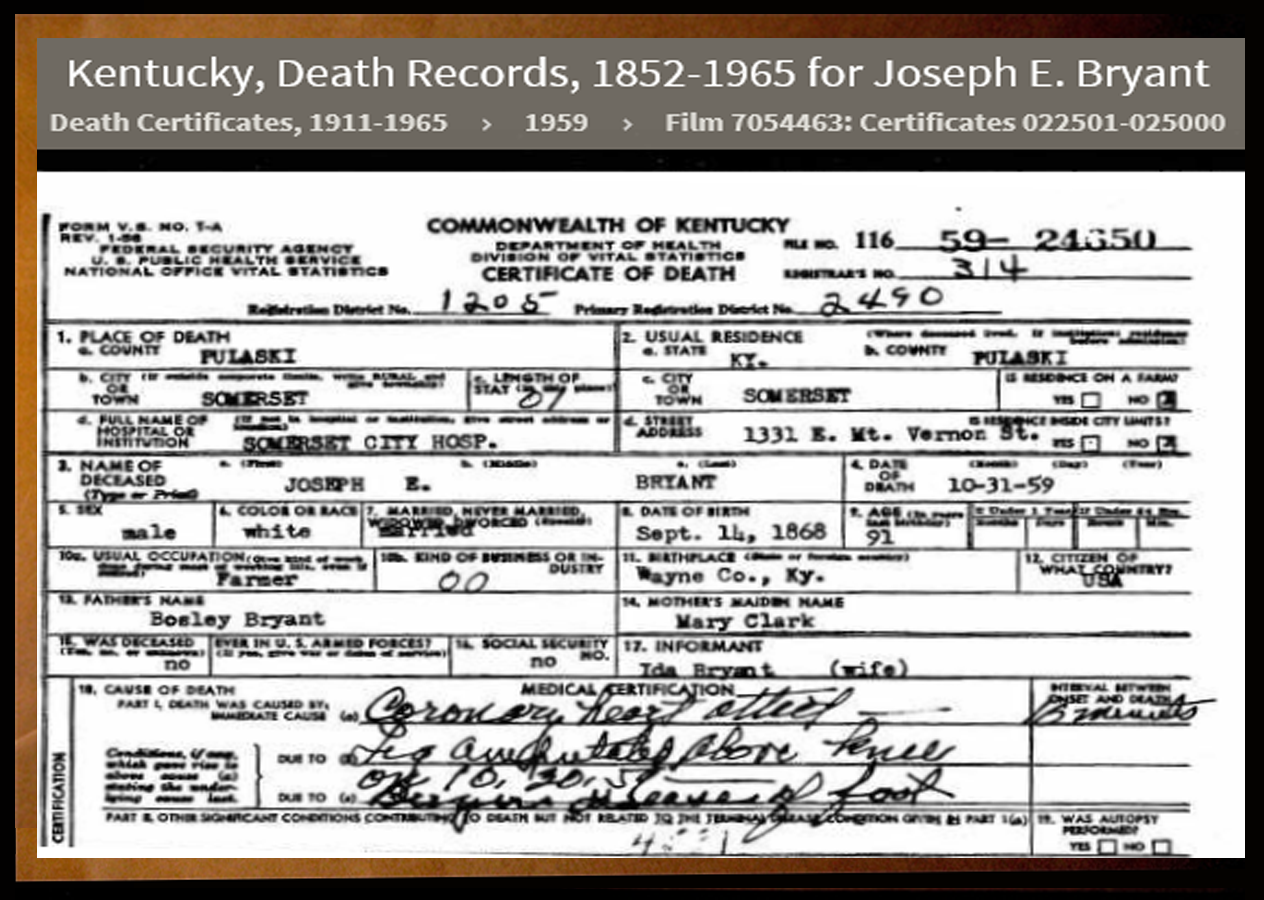

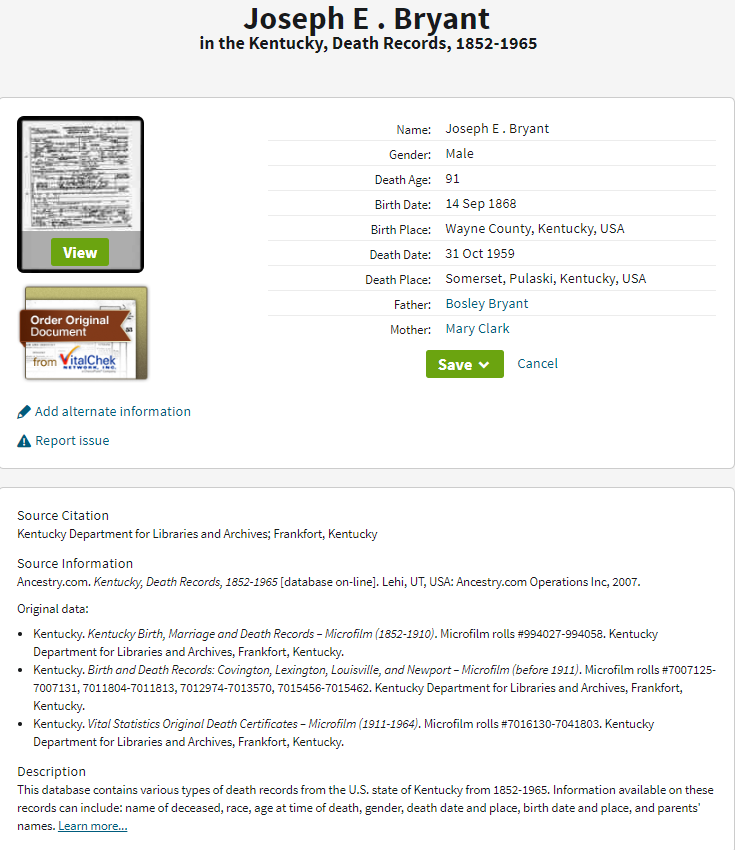

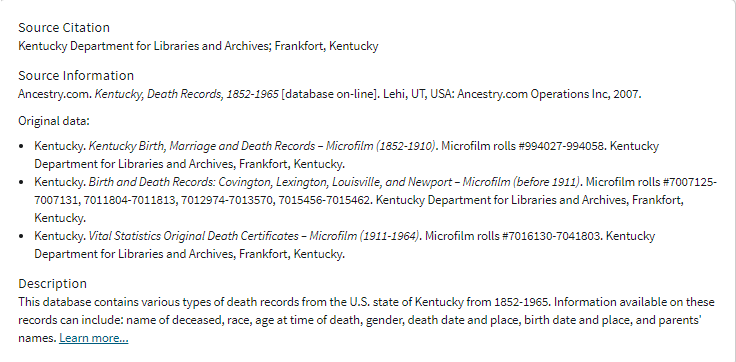

The snipped image offered by ThirtyOhSix illustrates our starting point:

In this case, Ancestry offers three forms of data:

- its database entry in which it has extracted2 basic details and presents them, neatly typed, in a tabular format

- an image of the original document

- three clusters of data that it calls “Source Citation,” “Source Information,” and “Description.”

ThirtyOhSix’s puzzlement—and that of most Ancestry users—lies in No. 3. To quote our enquirer: “What do I do with this information … if anything? I would think EE would want me to track down the right original data source and cite that instead, but if the best I can do is cite Ancestry and use the images provided, how would I proceed?”

Let’s tackle that assumption first.

Assumption

Would EE expect you "to track down the right original source data and cite that instead"?

Response

Not in this case. If Ancestry did not provide an image of this official document, then Yes, it would be wise to obtain a copy of the original and take our data from there. Trusting a derivative source to be accurate is a sure way to build brick walls in our research.

In this case, Ancestry provides an image copy. That does not mean that we just grab the image and fly on to something else. What it means is that we should evaluate Ancestry’s “Source Information” to decide how authentic, original, or authoritative the image is likely to be.

ThirtyOhSix backtracked the cited source to the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives. Then he studied the descriptive information that agency provides. From this, he learned that the images were made from microfilm created by and certified by the State Archives. The material that was imaged consists of individual certificates and appended affidavits from the state’s Office of Vital Statistics, arranged and numbered annually by year, then alphabetically by county, then chronologically by the date the state office processed its copy of the locally created data. So …

- Do we need to order a copy of the certificate through the commercial option that Ancestry offers in the snippet above? No. Odds are, the commercial firm would go to the same source Ancestry used and just make us a printout.

- Do we need to order a copy of the certificate from the State Archives? No. Odds are we’d just get an image from the film, which is what Ancestry itself delivers.

- Do we cite the State Office of Vital Statistics? No. Not as our source. That’s not where we obtained our information.

- Do we cite the microfilm created by the State Archives? No. That’s not what we used.

If we want to add a discursive note that describes what we’ve learned about this set of imaged records, that's fine. We can add anything in our research notes that we think will help our research. But that discussion would not be part of our basic citation. We will, however, consider part of it as we decide the details that need to be included as source-of-our-source data in the last field of our citation.

Question

What do we do with all the stuff in that 150-word description Ancestry has given us?

Answer

We read it thoughtfully. Then we make decisions.

First, we notice there’s a lot of repetition and redundancy. We don’t need that in a citation. Citations are already off-putting to many of our readers. Saying the same thing over and again will further discourage them from muddling their way through our citation. More importantly, it will discourage them from thinking about the reliability of what we are asking them to trust.

Second, notice that Ancestry’s “Source Information” does not tell us where Ancestry got its information. It just identifies the very database we’re using. It’s also doing that in Source List Entry format. That’s what we use in a completed bibliography or to create a “master source” in the software we use to organize our research. To create a “Reference Note” citation—what we use on a daily basis, every time we cite something—we will have to do some detail selection and rearrangement.

Third, notice that none of that detail, if we cited it, would get us to the image we want. This is the point at which we have to make our first decision. Do we want our master source to be

A. this database, which we can then use for all images we take from this collection?

B. this specific document, so that the citation will take us directly to that image?

Approach A: Focus on the Database

This is a simple format to create, following the basic approach for citing an online database:

“Name of Database in Quotation Marks,” type of database, Title of Website in Italics (URL : access or download date), specific item of interest; source-of-the-source data.

At the top of the snippet that ThirtyOhSix provided (or your Ancestry screen, if you’re following along online), we see the name of the database: “Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965.” We also see that database's name in Ancestry’s discussion of the source, under the heading “Source Information.” The only difference is that the citation under Source Information puts the database title in italics, as though it were a standalone publication. It’s not. The database is published only as part of Ancestry’s website. The website is the standalone publication. The database is just one part of that bigger publication, the equivalent of a chapter in a book or an article in a journal. Therefore we place the database name in quotation marks and the website name in italics, along with the URL to the website’s home page:

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” type of database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : access or download date), specific item of interest; source-of-the-source data.

We’ve already noted that this is a database with images. It’s not a basic database in which the only deliverable is the company’s keyboarded data. Our next step, now, is to add that “type of database” description to our citation:

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : access or download date), specific item of interest; source-of-the-source data.

Because this database has images, we will naturally take our information from the image.

Yes, that neatly typed database entry is much more readable, but it could have all sorts of copying errors. Therefore, in the “specific item of interest” field, we identify the specific certificate and add that we are using an image copy. Let’s also fill in the date field, specifying that we are downloading the image.

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : downloaded 1 March 2019), imaged certificate 59-24650, Joseph E. Bryant, died Wayne County, 31 October 1959; source-of-the-source data.

If there were some overriding reason why we must take our information from the database entry itself—say, the print is so faded on the image that we cannot read it for ourselves and we are temporarily recording Ancestry’s interpretation of it until we can order a copy that (we hope) will be clearer—our citation to the database entry would be this:

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 March 2019), database entry for Joseph E. Bryant, died Wayne County, 31 October 1959; source-of-the-source data.

This citation format is appropriate for everything we take from that database, whether we have just one certificate to cite or a thousand of them. All we need to do is switch out the data in our field for “specific item of interest.” This citation format, in fact, is appropriate for everything we take from any database at any site such as Ancestry; all we need do is switch out the details for names, URL, and specific item of interest.

Before we tackle the last element of the citation, the source-of-the-source data, let’s look at our second option for the structure of our citation.

Approach B: Cite the Exact URL or the Path

Rather than feature the database in a format that is reusable for many certificates, we might prefer to cite the exact URL or the path that takes us to the exact image. Typically, we do this when

- we are writing a paper for publication;

- we are preparing a research report for a client or for our own files; or

- this one certificate is the only one we use from this collection.

Citing the Exact URL

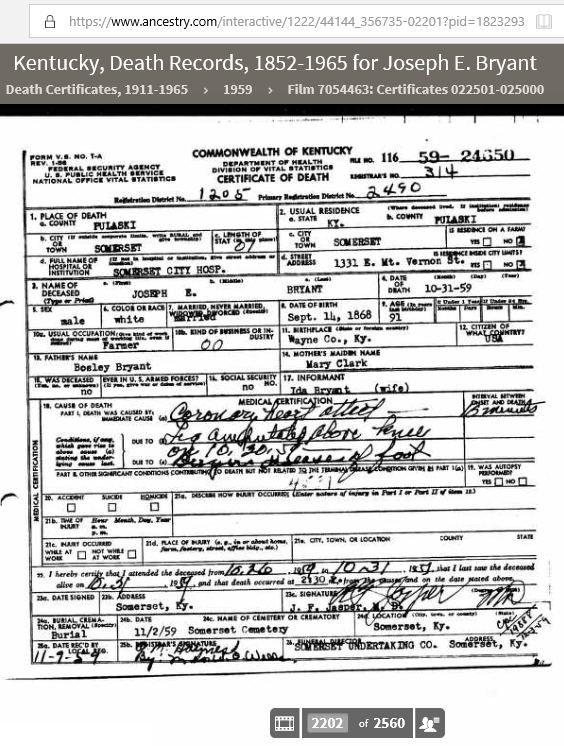

When we view the actual image, if we just copy-paste the URL, we usually end up with a half-dozen lines of gibberish:

https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/1222/44144_356735-02201?pid=1823293&backurl= https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll indiv%3D1%26db%3Dkydeaths%26gsfn %3DJoseph%2BE%26gsln%3DBryant%26gsfn_x%3D1%26gsln_x%3D1%26cp%3D0% 26new%3D1%26rank%3D1%26redir%3Dfalse%26uidh%3Dau1%26gss%3Dangsd %26pcat%3D34%26fh%3D0%26h%3D1823293%26recoff%3D%26ml_rpos%3D1&treeid =&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&usePUBJs=true

We can usually shorten that. Look for the first question mark. Typically, everything before that first question mark identifies the record. The rest can be lopped off, leaving us with this:

https://www.ancestry.com/interactive/1222/44144_356735-02201

This URL would replace our citation to the home page:

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com /interactive/1222/44144_356735-02201 : downloaded 1 March 2019), imaged certificate 59-24650, Joseph E. Bryant, died Wayne County, 31 October 1959; source-of-the-source data.

Citing the Path

Path data is easy to identify. As you can see from the certificate image above, when Ancestry delivers the image, it adds a source-data bar at the top of the screen. This one tells us that the database name is

“Kentucky, Death Records, 1852–1965”

The second line of data identifies the path, each element of which is separated by a greater-than sign:

Death Certificates, 1911–1965 > 1959 > Film 7054463: Certificates 022501–025000

When citing the path, we are citing the specific data someone needs to browse through the images, once they access the database. We have two choices for our URL:

- Ancestry’s home page, in which case a user of our citation would enter the database name into Ancestry’s home-page search form

- Ancestry’s landing page for that database, which would allow the user to browse the database or query for a name

To identify the URL for the landing page, all we need to do is click on the database name on the image’s source bar. That click will take us to the landing page for the specific database. There, in this case, we see that the URL is

https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1222

This URL should not be truncated. The final 1222 is the essential collection number. To create a path citation, using our URL of choice, we start with the same basic format we’ve been using:

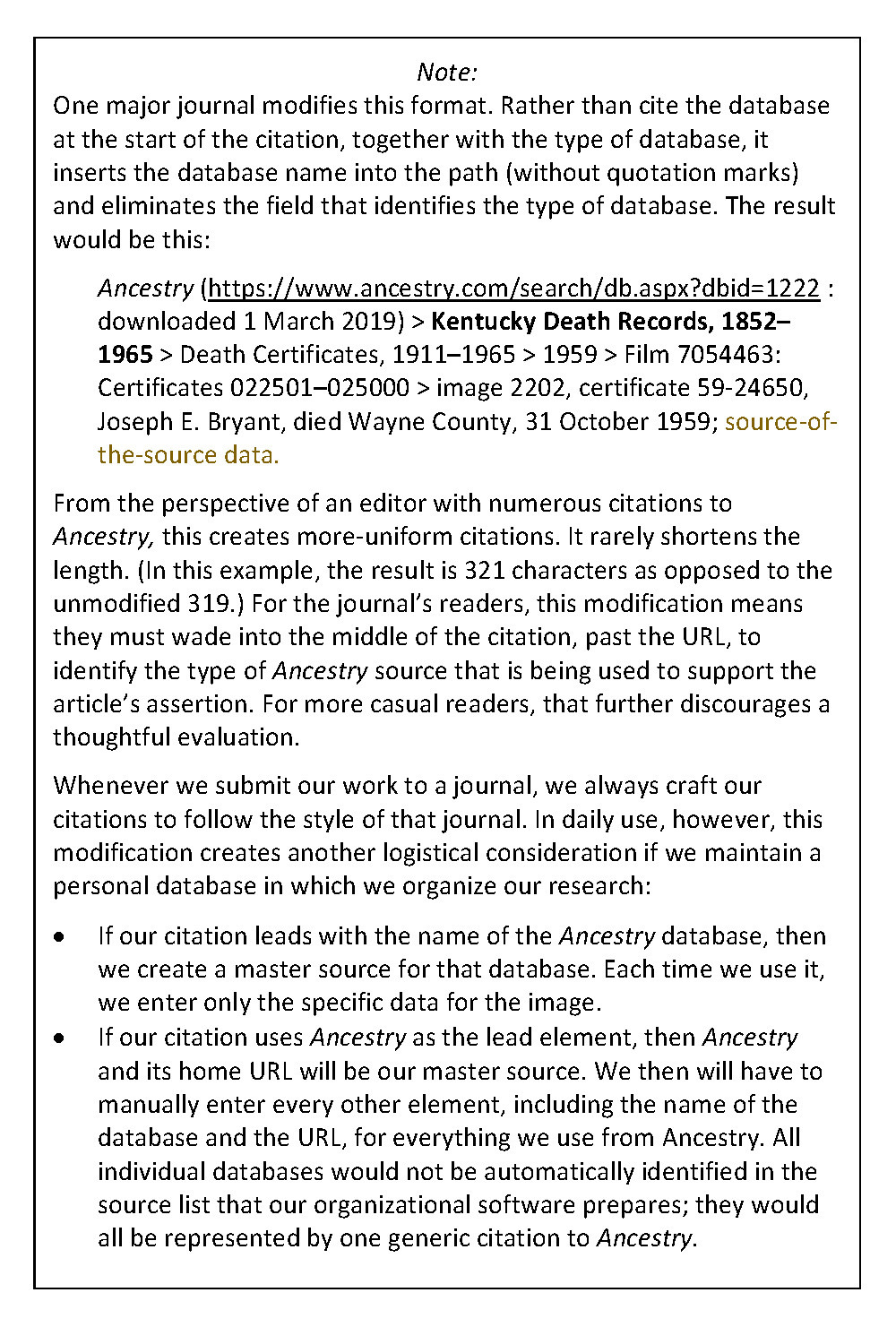

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry …

We then make the modifications needed to take us to our exact image. If we prefer that our URL take us to database's landing page, our citation would be this:

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1222 : downloaded 1 March 2019) > Death Certificates, 1911–1965 > 1959 > Film 7054463: Certificates 022501–025000 > image 2202, certificate 59-24650, Joseph E. Bryant, died Wayne County, 31 October 1959; source-of-the-source data.

If we prefer to use Ancestry’s home-page URL, our citation would be this:

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : downloaded 1 March 2019) > Death Certificates, 1911–1965 > 1959 > Film 7054463: Certificates 022501–025000 > image 2202, certificate 59-24650, Joseph E. Bryant, died Wayne County, 31 October 1959; source-of-the-source data.

Finally: What To Do with That Source-of-the-Source Data!

Have you noticed something yet? Our path data tells us that the image appears on “Film 7054463,” a roll of microfilm that presents all certificates from 022501 through 025000. Meanwhile, Ancestry’s discussion of its source tells us this:

Under “Original data,” Ancestry tells us that its images come from microfilm created by the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives. It specifies three separate microfilm collections created by that archives. However, none of those three cover “Film 7054463.”

?????

As regular users know, Ancestry’s databases continually grow (and sometimes disappear). New materials may be added to an existing collection, in which case the title may be changed to reflect the expanded materials. Ideally, those who make the changes to the database title will remember to update the “Source Information” that accompanies the database. In this case, given that three separate sets of “original data” are cited, it’s likely that Ancestry has updated, at least twice, its first incarnation of this database. Apparently, it updated yet another time and forgot to update its “Source Information” to reflect the inclusion of Film 7054463.

Or else a typo has been made.

In either case, we are reminded that when our source identifies its own source, we cannot just copy-paste what it offers and assume that all is correct. (It’s also a reason why “borrowing sources”3 is risky as well as unethical.)

Whatever data we’re given, we think it through. We analyze. We compare. We look for problems. Then we iron out those problems.

ThirtyOhSix proceeded to do that, studying the website of the Kentucky Department for Libraries and History and then backtracking from there to the Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics where this set of state-level records was created from locally-gathered data.

For the purpose of this lesson, one thing is left for us to do: complete our citation. What do we use for that source-of-the-source information we have not yet addressed? Of the three groups of information that Ancestry gives us about this source,

- we have eliminated the “Source Information” because that just identifies the database. It does not tell us where the database’s information came from.

- we also have eliminated the “Original data” section because Film 7054463 is not covered by any of the three cited sources.

That leaves only one piece of information to cite as our provider’s source-of-its-source: the one line that appears under "Source Citation." The result is this:

“Kentucky Death Records, 1852–1965,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : downloaded 1 March 2019) > Death Certificates, 1911–1965 > 1959 > Film 7054463: Certificates 022501–025000 > image 2202, certificate 59-24650, Joseph E. Bryant, died Wayne County, 31 October 1959; citing “Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives; Frankfort, Kentucky.”

You will note two things about our addition to the source-of-the-source field:

- Because we are quoting exactly what Ancestry cites, we put those words in quotation marks.

- We preface that source-of-the-source data with the word "citing" to tell our readers that Ancestry’s database cites this as its source.

The Bottom Line

What have we learned from this lesson? At least two things:

- We cannot just copy-paste a prefabricated “citation” and assume that it is correct or complete.

- The data delivered to us online has gone through numerous processes that can affect the accuracy of our research. Obviously, copying errors can occur when information is extracted from a source and keyed into a database. Not so obviously, when sources are repeatedly imaged (in this case at least twice), each processing presents a possibility that images could be omitted. (Ergo, it's worth asking ourselves: When we use images with negative results, do we search the entire series, for the appropriate time frame, to ensure that a hiccup in the mechanical reproduction process did not skip over our needed record? That happens more often than we’d like to believe.)

The “art” of crafting a citation requires us to think about what we are using, to think about the details that individuals need to locate the source—physically, as well as online—and to think about all the characteristics of the source that could affect its reliability.

SOURCE NOTES:

1. Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017) is a case at point. Five of its 1144 pages address citations to all forms of electronic sources (sections 14.205—14.210). The specific examples for “Citing web pages and websites” (at 14.207) are all examples for website articles, not for historical documents or databases.

2. Some Ancestry users refer to the these "extracts" as "abstracts" or "transcriptions." They are not. For the critical difference between extracts, abstracts, and transcriptions, see the Glossary provided in QuickLesson 10: Original Records, Image Copies, and Derivatives.

3. "Borrowing Sources" refers to the unethical practice of using a derivative source and copying its citations rather than citing the derivative we actually used—thereby making it appear that we consulted the originals. Aside from ethics, it also misleads our own research. When we later come back to the citation after our recollection has gone cold, we will also assume that we used the original. If we had cited the derivative we actually used, that reference to the derivative would be a flag reminding us to seek out the original to ensure that the data we took from the derivative is accurate. For more on "borrowing sources," see QuickLesson 15: Plagiarism—Five "Copywrongs" of Historical Writing."

HOW TO CITE THIS LESSON:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, "QuickLesson 26: Thinking Through an Ancestry.com Citation," Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-26-thinking-through-an-ancestry.com-citation : posted 2 March 2019).