Each record that survives from the past represents a milestone in the lives of those involved. For us, as we explore history, each record should be a stepping stone to something more. More always lies beyond for those willing to scrape away the moss of quirky language and the grit of changing legal landscapes.

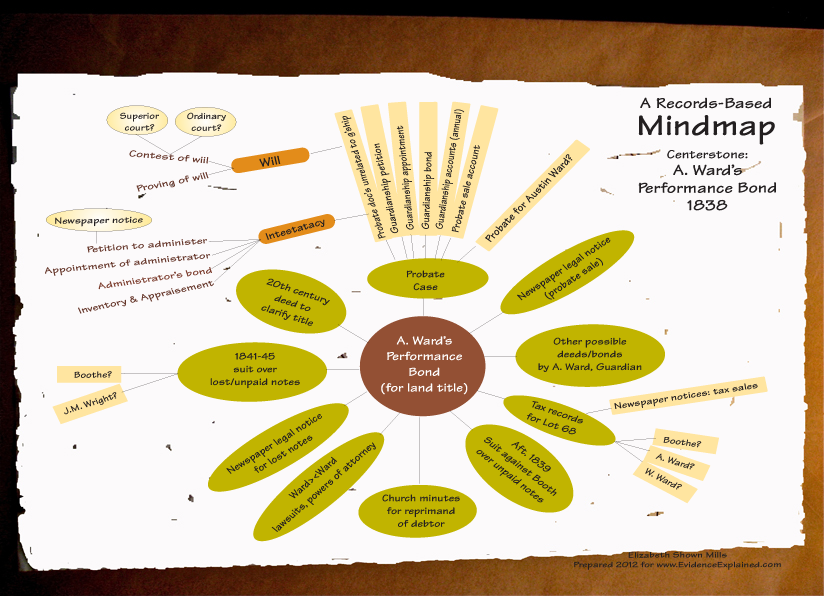

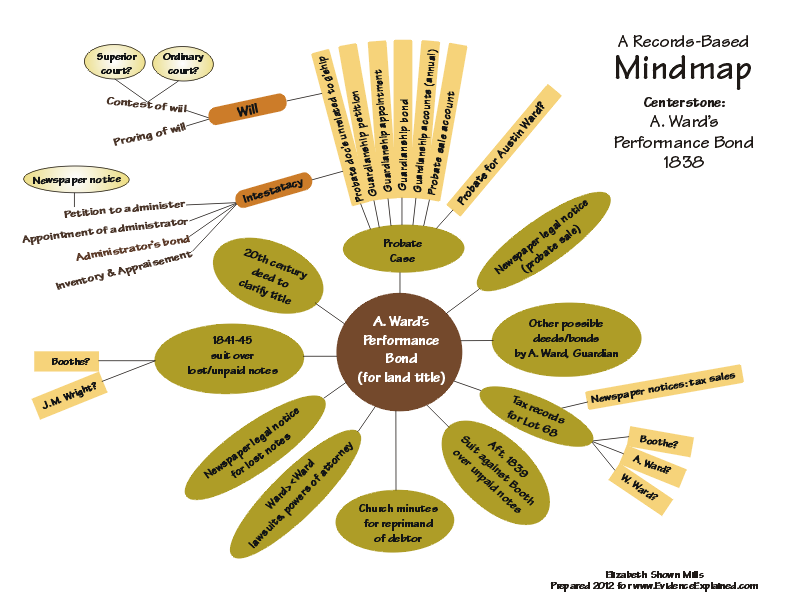

A well-analyzed record is a centerstone from which many research paths diverge. That premise presents its own problem: how do we brainstorm the possibilities? How do we track the alternatives?

Mindmapping is one tool we can adapt. British psychologist Tony Buzan, who made mindmapping a modern buzzword, argues that constructive thinking is a free-flowing process—one that branches in unpredictable directions around a single key word.1

Our equivalent is not a word but a document. The research map we need, for each record we find, is one we have to create ourselves. Many available graphs depict for us the organizational structure of historical records. Most are based on record type. Their emphasis is very much upon organization and structure. A research path through historical materials, however, is organic and unpredictable. Its possibilities and its shape depend upon the details of each individual record and the singular life of each person involved in that that record.

CASE AT POINT

QuickLesson 5 analyzed a well-layered document we can use to demonstrate a records-based application of mindmapping. In brief, the circumstances were these:2

- In December 1838 Austin T. Ward of Stewart County, Georgia, penned a performance bond, obligating himself to pay $800 to a fellow resident of the county if he did not fulfill certain terms. In the wake of the financial Panic of 1837, Ward—as guardian of the minor heirs of the deceased Richard Ward—had offered at public auction a lot belonging to those heirs.

- Milton S. Boothe bid $400, but had no cash. Instead, he offered his promissory note due in December 1839. Ward accepted, but required Boothe to give fourteen separate notes, all in small denominations so that Ward could sell them more easily if an emergency arose. Via the performance bond, Ward swore that he would give Boothe a valid title to the property once the debt was paid.

- Boothe could not pay his bill when it came due. Ward extended the debt, taking another small note to cover accrued interest. One John M. Wright co-signed the new note, as security for Boothe.

- By January 1841, Ward had assigned the notes to one William G. Ward, who had the misfortune to lose his “pocket book” with all the notes inside. William Ward advertised the loss to warn finders against any attempt to sell the notes.

- In December 1845, a witness to the 1838 bond went before a local justice of the peace to affirm that he had seen Austin Ward execute and assign the bond. He did not identify the person to whom the bond (and presumably the notes) had been assigned.

- In September 1847 the bond and the witness’s affidavit were recorded in the deed registers of the county clerk. The purpose of the filing was not stated. Ostensibly, it was recorded to document the transfer of the lot’s ownership.

Like many documents of its era, this performance bond left researchers with more questions than it answered. Like most, this document is a virtual centerstone from which many research paths devolve. For biographers of Austin Ward and Milton Boothe—or those who study the effect of the 1837 crash upon rural Georgians—many of the questions this document raises should be answerable by mapping and then pursuing those pathways.

Our Mindmap

Below, we color-map the most productive options we might take. Some record paths are a stepping stone to be tested, primarily the green ovals. Among them, three possibilities are more-complex ventures, each offering alternate lanes and byways to be explored.

Probate case

The first stone in this rambling path through Stewart County history was laid when Richard Ward died. He may have died testate (i.e., leaving a will), by the terms of which he chose his own heirs. That document would typically, but not always, dentify the minors who go unnamed in Austin Ward’s bond. A will might also designate Austin to serve as guardian of the minors’ financial interests. Or Richard Ward may have died intestate (without a will), in which case heirship would be determined by Georgia law.3 Each of these alternatives created a different path for legal proceedings to follow.

- If Richard Ward left a will, then his named executor would present it to the court for proving, at which time a witness to the will would attest its validity. If the will was deemed valid, then so long as the named executor carried out the provisions of the will, few other documents would typically be filed—unless the provisions of the will were unusually complicated. If some heirs chose to contest the terms of the will, the paper trail might be confined to the probate court (i.e., the Court of Ordinary, in that time and place) or it might cross over into the more-general court system (that, in Georgia, being each county’s Superior Court). From there, it might also progress up a chain of appeals.

- If Ward died intestate, then an heir, a creditor, a relative, or some other party with a legitimate interest in the matter would petition the court to be appointed administrator of the personal property and real estate. If approved by the court, numerous documents could ensue that were unrelated to the guardianship: i.e., administrator’s appointment, administrator’s bond, an inventory and appraisement of Ward’s property, a probate auction, a financial account of the sale, and a final account on the estate. If any forced heirs (those specified by Georgia’s law) were minors, the paper trail should include a guardianship petition, appointment, bond, and (typically) annual accounts until the last of the minors reached twenty-one or (if female) married.

A thorough exploration of the probate files might also include a probate case for Austin Ward. Given that William Ward, in January 1841, was in possession of the notes Boothe had made in favor of Austin Ward, Austin’s death in that interval is at least a possibility. Alternative explanations for Austin Ward’s assignment of the notes might be his financial distress or his removal from the region.

Published legal notices

Amid these probate proceedings, certain actions required the publication of legal notices in the newspaper that officially served that county. The two events that most-commonly triggered a legal announcement were a request for administration and the scheduling of a probate sale. In complex cases, multiple sales might be held. One such sale was likely, but not necessarily, the event that Boothe attended. Because most probate sales were community-based, attendees were commonly friends, kin, and neighbors of the deceased. Thus, Boothe and the Ward family could have had a close relationship prior to the 1838 sale of the lot on terms quite accommodating to Boothe. However, as guardian of the minors, Austin Ward also might have chosen to hold his “public outcry” of the lot in the courthouse square. More thorough research should determine whether a Ward-Boothe relationship existed before the sale.4

Other deeds or bonds

A thorough research path would also include a reexamination of the deed books for other documents relating to any of the individuals involved. The context they provide could be enlightening or it could be crucial.

Tax records & tax-sale notices

Annual tax rolls, both assessments and collections, were mandated by Georgia law. Few of these survive for early Stewart County. The one roll critical to the period in question, 1841, should clarify whether Boothe remained in possession of the property or whether its management had reverted to Austin or William Ward. Given the dire economic times, newspapers should also be consulted throughout the 1839–47 period for the annual notices of tax sales scheduled for properties whose taxes were delinquent.

Church minutes

Any surviving record books of churches in the vicinity of the Ward and Boothe residencies might shed additional light on the economic difficulties faced by these men—particularly Boothe. Many men were not churchgoers in this society, but those who held membership in a Protestant denomination were expected to settle their debts in a conscientious fashion. Protestant minutes frequently record admonishments of church members who were perceived as dodging financial obligations. If, in the middle of financial difficulties, a member decided to move elsewhere and asked to transfer his letter of membership, that letter might be denied. Those requests and the decisions upon them were also, typically, recorded in church minutes.

Ward-Ward lawsuits or powers of attorney

William Ward’s published notice of January 1841, stating that he was the legal owner of the notes held by Austin Ward, suggests further legal transactions between these two men during the 1838–41 time frame. The notes might have been transferred as a result of debt. Or, if Austin Ward chose to move elsewhere, he might have appointed William Ward to serve as his attorney of fact (i.e., an agent, not an attorney-at-law) to settle his financial and legal affairs in Stewart County. In both cases, transactions are typically found in the court minutes or deed books.

Newspaper legal notice for lost notes

At least one such milestone on the Ward-Boothe paper trail has already been found. Others might exist.

Legal suit over lost and unpaid notes

As noted in QuickLesson 5, William Ward’s 1841 mishap with his pocket book full of notes created an escape hatch for Boothe, if he sought relief from his financial obligation. The documentary trail clearly shows that the case was settled by September 1847 and likely by December 1845. The possibility of legal action in this period is great enough to warrant a thorough search. Any legal action against Booth’s surety, J. M. Wright, should also be studied.

20th century deed to clarify title

The 1847 filing of the performance bond originally signed by Austin Ward puts on record his intent to provide Boothe with a clear title to the lot. However, the filing of that bond as a substitute did not constitute a clear title with a guarantee against any and all encumbrances. In many such cases, after the passage of the number of years stipulated by state law, the holder of the property would take legal action to obtain a clear title deed. Most such documents are found amid twentieth-century deeds or court records.

Our Bottom Line

Historical research rarely, if ever, takes a straight path from the point of our initial inquiry to the point at which we feel our questions have been answered. By nature, our research begins with the known and plows through the unknown until a conclusion is justified. Thorough research can prompt many detours and changes of direction. But every successful effort will begin with a plan—one that should be continually reassessed as our efforts eliminate some possibilities and uncover new ones. Throughout the course of a project, mindmapping is a valuable tool to keep our work focused and thorough.

2. Stewart Co., Ga., Deed Book Q:368, as provided and cited by Allison Graves (au90grad@hotmail.com).

3. QuickLesson 5 details (and cites) the major provisions of Georgia law that would apply to this case. The basic reference work is Thomas R. R. Cobb, ed., A Digest of the Statute Laws of the State of Georgia in Force Prior to the Session of the General Assembly of 1851, vol. 1 (Athens: Christy, Kelsea & Burke, 1851); accessible via Google Books (Books.google.com). Unnumbered page 290 of this digest provides a “Table of Descents,” charting the heirship paths Georgia law would take.

4. Georgia’s statutes in this era required auctions “before the courthouse door” for notes, bonds, debts, and financial transactions, as well as slaves. However, it did not pose that requirement for probate sales of land and personal property. See, for example, Cobb, Digest, pages 131, 139, 338, 513–14, and 978.

How to cite this lesson:

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 6: Mindmapping Records,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-6-mindmapping-records : [access date])