Some assembly required. Please read instructions! Historical documents don’t come with this label, but they should. Students, scholars, and family sleuths who work with the nuts and bolts of past societies love the challenge of assembling history’s raw materials into Wow! moments. Like DIY-ers everywhere, many also scoff at the thought of reading instructions.

Census records make that point. Censuses were taken. Enumerators went from tenements to farms, gathering names. They sent their scrawled sheets to bureaucrats who like to count and tally. Those sheets have now been digitized. Online providers give us instant access. Search engines find our names of interest. We need only copy down the data. Then we’re ready for the assembly—merging the new-found information into the biography we are writing or the community structure we are studying.

Duh! Census research could not be any easier. What schmuck needs instructions?

We do. The past was a foreign country, where people did things differently. They had needs and customs that differered from ours. They followed processes that seem counter-intuitive to modern minds. They used words in ways we’d never anticipate. Every document that survives is a gotcha waiting to happen if we do not understand the circumstances under which that document was created.

Meet the Peppers

A wise beginner, a while back, posted a query in an online list-serve. The forum need not be named. This or that respondent can remain anonymous. But their exchange of thoughts triggers a useful lesson.

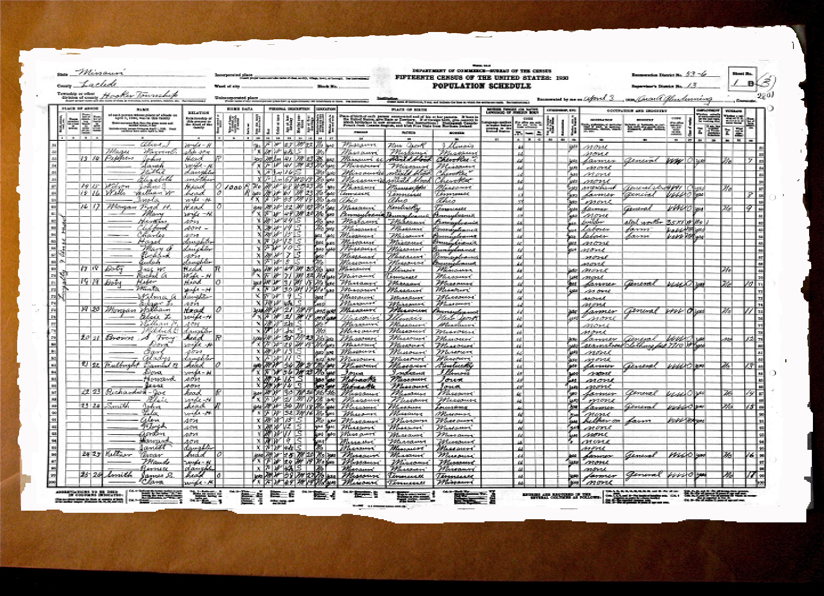

On 3 April 1930, a U.S. census worker named Orion A. Glendenning visited the home of John and Sarah Peppers in Hooker Township, LaClede County, Missouri. He asked the standard questions, drawn from a standard form. But he did not get standard answers. The Peppers, unlike their neighbors, identified themselves as “Indian”—mostly. Only the wife Sarah is said to be white. Then Glendenning “adapted” his standard form in curious ways.

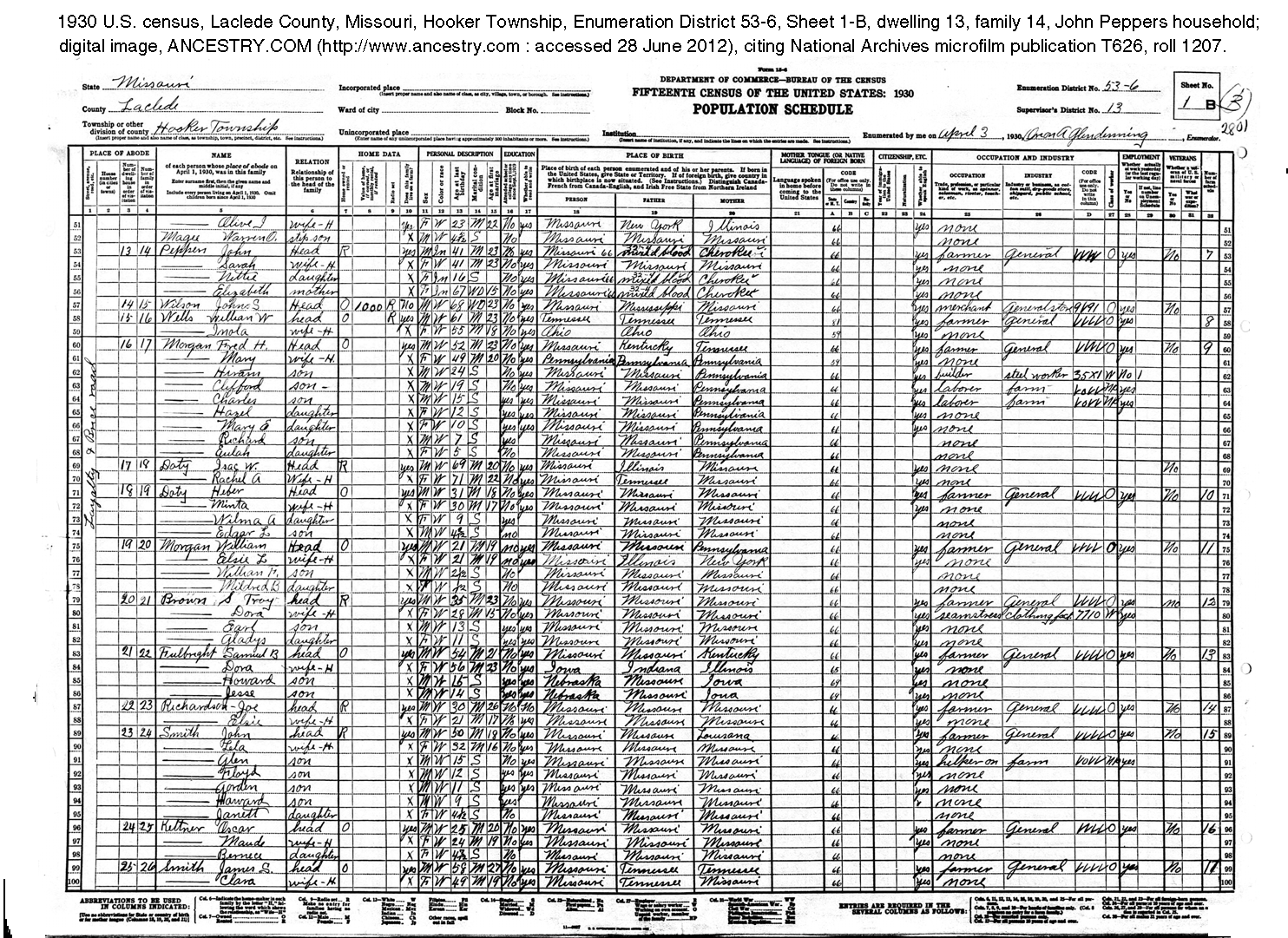

Three columns of that census call for “Place of birth.” A header to those columns provides instructions that Glendenning seems to have ignored. The resulting record tells us the following (and a bit more) about that householder, his wife, his daughter Nettie, and his mother Elizabeth:1

“Cherokee” could be construed as a reference to the Cherokee Nation, but “mixed blood” clearly is not a place of birth. Does Clendenning’s substitution of data not asked for on the form suggest something of his mindset? Does it reflect, perhaps, a community’s curiosity about minorities who lived in their midst?

Researcher A, the list-serve inquirer who discovered the census entry, focused on the numbers added to the birthplace column for each of those deemed “Indian.” Specifically:

- Might the “66” identify a reservation to which the Peppers belonged?

- Might the “32-4” represent their “blood quantum”? (Yes, that quaint phrase is a serious issue in many records of Native American tribes—to this day.)

Researcher B, a helpful respondent, had a different interpretation, starting with these two points that "B" deemed obvious:

- Because John was said to Indian (the child of a mixed-blood father and a Cherokee mother) and because John had a white wife to whom the census said he had been married since they both were 23, then Nettie’s mother’s column clearly should not identify that mother as Cherokee.

- The enumerator, instead of seeking correct data for John’s daughter Nettie and John’s mother Elizabeth, had lazily repeated John’s data on the lines for the other two Indian family members.

In sum, “B” decided: the information is incorrect, the enumerator did not follow his instruction, and the result demonstrates the kind of incompetence researchers have to work around when using census records.

Do you agree? Or would you prefer to read the instructions?

The Critical Instructions

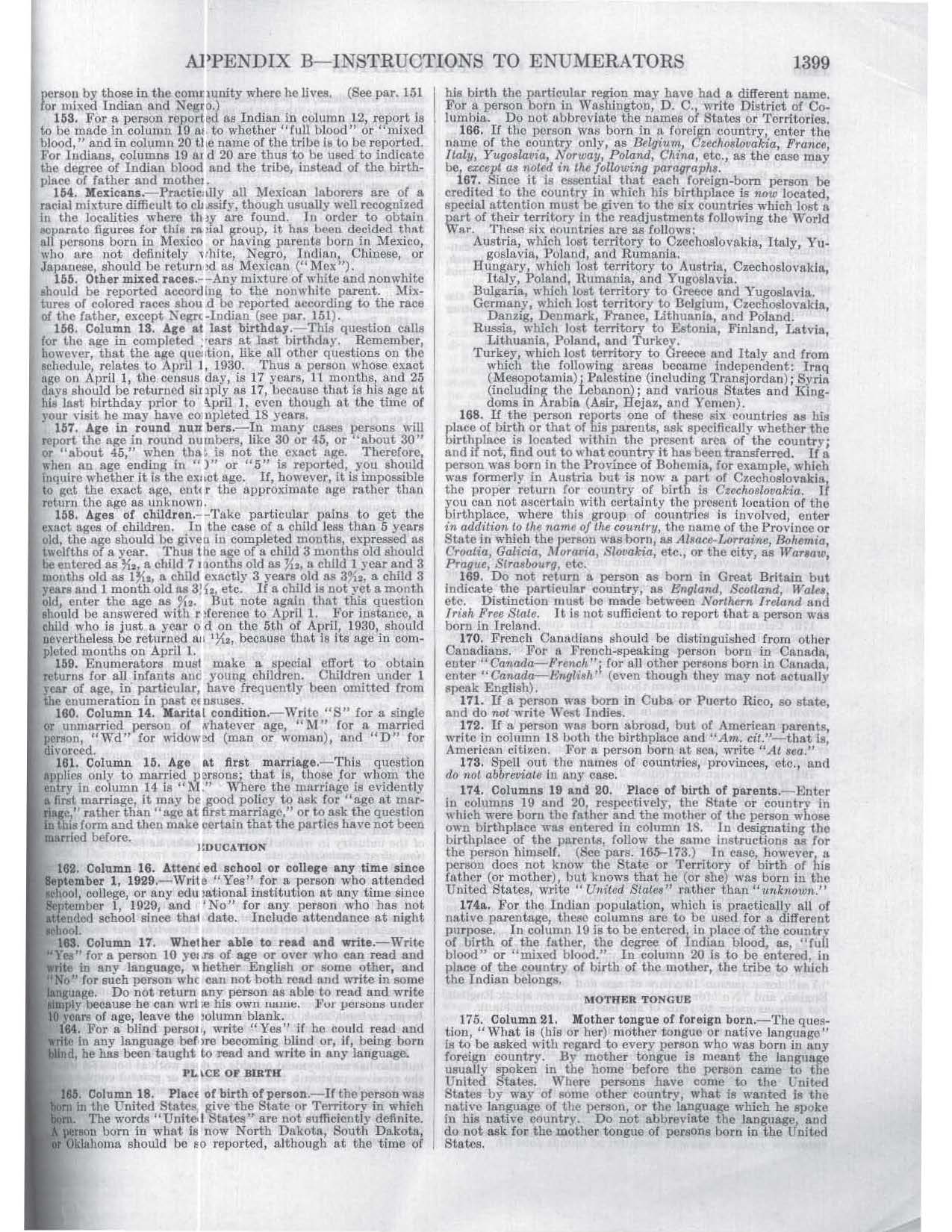

All that wordy text under “Place of birth” carries a can’t-miss reminder that more instructions do exist. In fact, seven pages of fine print were given to the 1930 census takers. Not seven pages of helpful suggestions, but seven pages of mandates they were to follow. Like many records from yesteryear, those instructions do not come conveniently bundled for us amid those census databases that we covet. But all have been digitized and are easily found through Bing or Google.2

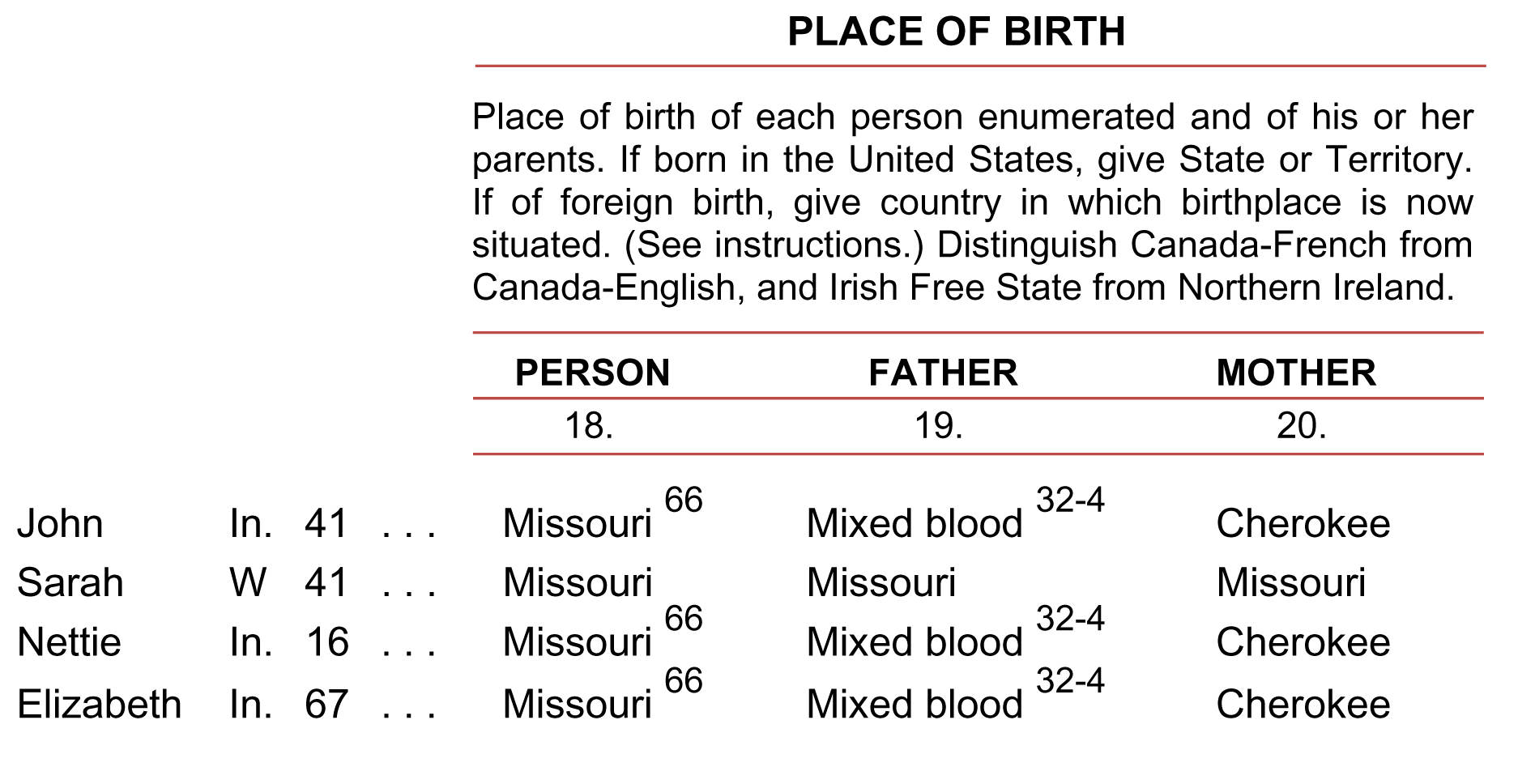

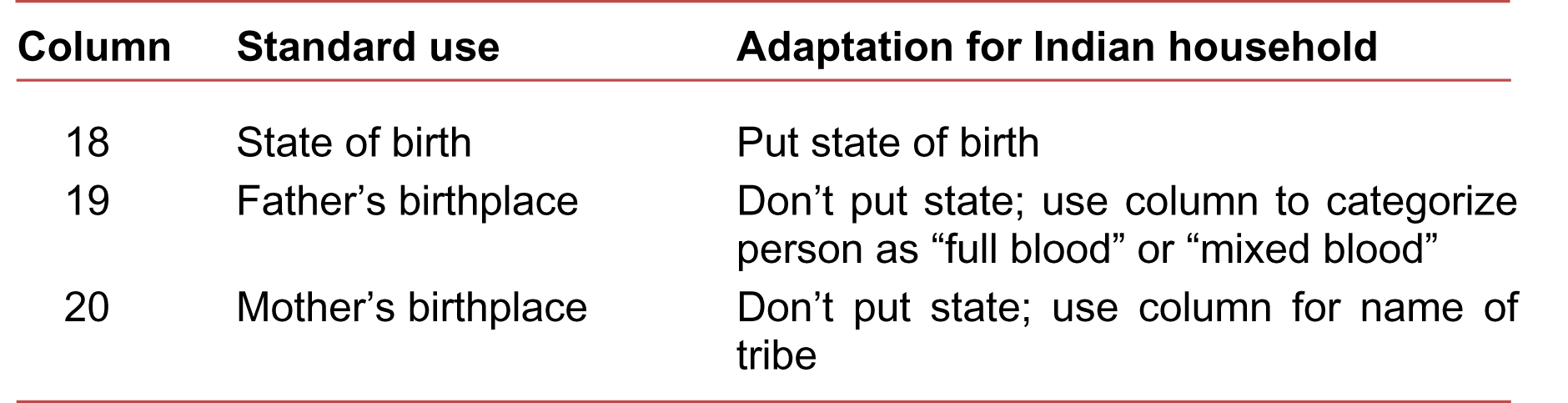

Eleven paragraphs of those instructions deal with how the census taker should interpret and record “Place of birth.” Two critical paragraphs focus on Columns 19 and 20, whose headers say to record the birthplaces of each person’s father and mother. However, as Para. 174a decrees, those columns had a different purpose for citizens who self-identified as “Indians”:

“[Para.] 174. Columns 19 and 20. Place of birth of parents.—Enter in columns 19 and 20, respectively, the State or country in which were born the father and the mother of the person whose own birthplace was entered in column 18. In designating the birthplace of the parent, follow the same instructions as for the person himself. (See pars. 165–173.) In case, however, a person does not know the State or Territory of birth of his father (or mother), but knows that he (or she) was born in the United States, write 'United Slates' rather than 'unknown'."

“[Para.] 174a. For the Indian population, which is practically all of native parentage, these columns are to be used for a different purpose. In column 19 is to be entered, in place of the country of birth of the father, the degree of Indian blood, as, 'full blood' or 'mixed blood.' In column 20 is to be entered, in place of the country of birth of the mother, the tribe to which the Indian belongs.”3

In other words:

Clendenning, the census taker did, indeed, follow his instructions. The error was that of Researcher B, who proceeded to “assemble the evidence” without reading those relevant instructions.

But What about Those Numbers?

Here, “B” offered options. The statistical notations 66 and 32-4, “B” opined, might have been written by either the census taker or a government statistician.

Do you agree? Or have you paused yet to read all of that 7-page guide linked to "instructions" above?

Nowhere, in those 1930 instructions do we find a directive telling the enumerators to enter codes of any type. Those cryptic numbers and checkmarks we see so often on U.S. censuses are tallies and codes added by the Census Bureau’s number crunchers—the diligent souls who reduced household data to stats by which they could define the social fabric of our nation.4

As history researchers who leave no clue unsqueezed, we are still left to wonder: What do those two sets of numbers represent? and Are they relevant to our research? As usual, we can glean those answers from a textual analysis of the 13 pages that enumerate Hooker Township of Laclede County.

Code “66”= State of Birth

From a scrutiny of the same page on which the Peppers are enumerated, we may draw two things:

- The code “66” has one other usage on that page. It appears in Column 21a, which carries the following header: “Code (For office use only. Do not write in this column)—State or M. T.” (Thus, we learn that the coding was not done by the local enumerators.)

- Every person whose line entry carries the “66” was born in Missouri. (For a neighbor born in Tennessee, the code is “81”; for a neighbor born in Iowa, the code is “65”; for neighbors born in Ohio and Pennsylvania, the code is said to be “59” in both cases.5

Code “32-4” = Mixed-blood Cherokee

If, as Researcher A hypothesized, “32-4” represents blood-quantum, then the components are curiously reversed. In standard practice, a fraction would be written 4/32, which would then be reduced to its smallest form: 1/8.

Again, we can define the code by scrutinizing Hooker Township’s returns for the other ways in which these pencilled notations are used. Three sets of similar codes appear on these thirteen pages:6

32-4 Used for citizens identified in Columns19-20 as mixed-blood & Cherokee7

91-5 Used for citizens identified as full-blood and Mawhee8

97-4 Used for citizens identified as mixed-blood and Mawhee9

The pattern that is implied above (one that holds true in random samples throughout the census) identifies the tribe with the first number and the mixed-or-full status with the second number. In answer to the specific questions posed by Researcher A: The codes used for the Peppers family do not identify any Native American reservation and they do not state a specific blood-quantum.

The Bottom Line

As with the bulky boxes we lug out of home-improvement stores, the instructions that explain our records are there for a purpose. Regardless of the type of record we are working with—censuses, deeds, military records, naturalizations, pensions, probates, or tax rolls—each was designed to comply with a set of regulations or laws unique to the time, the place, and the class of record. Accurate interpretations seldom happen when we ignore our instructions.

1. 1930 U.S. census, Laclede County, Missouri, Hooker Township, Enumeration District 53-6, sheet 1-B, dwelling 13, family 14, John Peppers household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 28 June 2012), citing National Archives microfilm publication T626, roll 1207.

2. These census instructions from 1790 through 2010 are available as digital images or HTML text from various online providers. This QuickLesson uses "Appendix B—Instructions to Enumerators,” North Carolina State University Libraries, Decennial Population and Housing Censuses Guide (http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/documents/guides/popcensus/images/1930enu.pdf : accessed 28 June 2012), PDF images of pages 1396‒1402 of a publication the site identifies (at http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/guides/popcensus/1930.html) as “1930 Population Census, vol. 2, pt. 8.” The source appears to be Leon E. Truesdell, Alba M. Edwards, and U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930; Population, 6 vols. in 7 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931‒33).

3. "Appendix B—Instructions to Enumerators,” 1399.

4. For analyses of other types of markings commonly seen on census pages, see Elizabeth Shown Mills, “Interpreting the Tick Marks on Federal Censuses,” Ancestry Daily News, 11 March 2004; archived at Ancestry.com, Learning Center (http://www.ancestry.com/learn/library/article.aspx?article=8265). Mills, “Census Tick Marks and Codes—Revisited,” Ancestry Daily News, 20 December 2004; archived at Ancestry.com, Learning Center (http://www.ancestry.com/learn/library/article.aspx?article=9465). Mills, “Census Tick Marks and Codes—Revisited Yet Again!” Ancestry Daily News, 4 January 2005; archived at Ancestry.com, Learning Center (http://www.ancestry.com/learn/library/article.aspx?article=9505). All three articles are also archived at the author's website, Historic Pathways (http://www.HistoricPathways.com).

5. A coding error occurred here. The code “59” is used for others born in Ohio, but no other Pennsylvania natives appear in this township. For Pennsylvanian natives living elsewhere in LaClede, the code was “58.”

6. To comply with copyright restrictions, images of all thirteen pages cannot be reproduced here. You may access them through standard providers such as Ancestry.com or HeritageQuest.com.

7. Sheet 2-B, dwell. 41, fam. 43, Lloyd and Laura Bell, and dwell. 43, fam. 45, Perry Waller family; also sheet 3-B, dwell. 71, fam. 75, Floyd, James, and Cecil Peppers; also sheet 7-A (stamped no. 165), dwell. 151, fam. 158, Fred Treasey.

8. Sheet 7-A, dwell. 150, fam. 157, for wife Mary J. Graves.

9. Sheet 7-A, dwell. 150, fam. 157, for children Martha, John W., Mary R., and William R.; dwell. 151, fam. 158, Teanie Treasey.

How to Cite This Lesson

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 9: Census Instructions? Who Needs Instructions?” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-9-census-instructions-who-needs-instructions : [access date]).