Humans have adopted clothes for protection. They are adaptable to circumstances. We can layer them to fit the environment or weather. Society has created all sorts of ‘rules’ for when and where to wear certain items of clothing. We don't wear white after Labor Day. We don't wear jogging shorts to a formal wedding. Yet the layering process remains flexible. On a fall day, we may put on a sleeveless vest or short-sleeved tee atop a long-sleeved shirt; as the sun climbs, we’ll peel off the lighter item and keep on the long sleeves to ward off the chill. On a summer night, we may don a long-sleeved shirt atop our sleeveless garb, as breezes cool the air. Jackets are layered on for heavy-duty needs.

All this can be said for citations as well. They exist for protection. Convention dictates certain practices, but we can add, shuck, or rearrange layers as needed to fit our circumstances. We need that flexibility more today than ever, considering how modern technology morphs our sources and delivers content through endless (and endlessly changing) media.

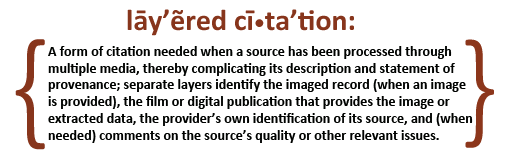

Aside from plain-vanilla print publications or artifacts we can physically hold, most citations involve layers in varying combinations:

- a layer to cite an original item that has been digitized;

- a layer to cite the microfilm or online provider through which we’ve viewed the image—or to cite a database entry or article offered by an online provider;

- a layer to cite the provider’s source-of-its-source;

- a layer to create our own description of the source or an analysis of its reliability.

The order in which we layer these will usually depend upon

- The nature of what we’re citing;

- The manner in which we’ve arranged our source list; or

- The complexity of the URL we need to cite for electronic delivery.

Amid all this flexibility, there are just three basic rules to remember

- Websites are publications; citations to them follow the basic pattern for published books. If it’s a single-subject website, it’s cited like a simple book. If it’s a website with multiple items, it’s cited like a book that has various chapters by different authors.

- Websites, like books, can offer (a) material written or compiled by the site owner/creator or (b) images of original documents, photographs, etc.

- Details from one layer should not be inserted into a different layer; each version of the record has its own distinctive details.

In the Reference Note examples that follow, we’ll treat all of these considerations in various combinations, using this color code: Layer 1 = black; Layer 2 = red; Layer 3 = green.

Census Records

Original returns accessed on microfilm

1790 U.S. census, Beaufort District, South Carolina, p. 492 (penned), col. 3, line 26, Mary Odam; National Archives microfilm publication M637, roll 11.

Original returns accessed through an online provider:

1790 U.S. census, Beaufort District, South Carolina, p. 492 (penned), col. 3, line 26, Mary Odam; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 4 September 2014); citing National Archives microfilm publication M637, roll 11.

Census extracts offered by the database provider:

“1790 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 4 September 2014), entry for Mary Odam, Beaufort, South Carolina; citing National Archives microfilm publication M637, roll 11.

POINTS TO NOTE (Original Documents)

- When we view an original document on microfilm, our citation has at least two layers: (1) the original document; (2) the film that reproduces it.

- When we view an original document online and the digitized image has been reproduced from film, rather than from the original document, we have at least three layers: (1) the original, (2) the online provider that delivered it to us; and (3) the film, as identified by our provider.

- We identify the film and the provider because the quality of reproductions differs between imaging crews and publishers; pages may be missing or they may be more or less legible, depending upon the publication or provider we use.

POINTS TO NOTE (Database Entry or Extract1):

- We are not citing the actual census. The database itself is our source and our principal layer. That database entry or extract is a new creation by someone who attempted to interpret the intent of the original enumerator. That derivative and the original document have significant differences in form—if not substance. A reasonably well-done database will provide source-of-its-source information, which would comprise our Layer 2. If we take data from a database that does not identify its source, we have only one level to cite; but wisdom suggests adding a second layer to comment upon the lack of source information.

- As per Rule 1 above, when a website offers multiple databases by different people, the creator of a database is typically identified prior to citing the database title—as one would do in citing, say, a book chapter by an author in a book that has different chapters by different authors. However, in the Ancestry example above, the creator’s name is also the name of the website, as well as the root of the URL. In such cases, to cite Ancestry.com, [“Database Title”], Ancestry.com (http://www.Ancestry.com) would be excessively redundant.

And, of course, you will have noticed:

- Each layer is separated by a semicolon. This punctuation follows a longstanding practice used when citing original manuscripts, where the organizational heirarchy used by archives has natural layers (document ID; file ID; collection ID; series ID; record group ID; archive & location).

Online Records at State-Agency Sites:

Original document digitized by & accessed through an online provider—with emphasis on document:

Thomas Dunn file, Revolutionary War Bounty Warrants; Executive Department Office of the Governor, Record Group 3, Virginia State Archives, Richmond; consulted through “Online Catalog: Basic Search: Rev. Bounty Warrants,” database with digital images, The Library of Virginia (http://lva1.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/F/?func=file&file_name=find-b-clas39&local_base=CLAS39 : accessed 5 March 2016).

Original document digitized by & accessed through an online provider—with emphasis on provider:

“Online Catalog: Basic Search: Rev. Bounty Warrants,” database with digital images, The Library of Virginia (http://lva1.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/F/?func=file&file_name=find-b-clas39&local_base=CLAS39 : accessed 4 March 2016), Thomas Dunn file, Revolutionary War Bounty Warrants; citing Executive Department Office of the Governor, Record Group 3, Virginia State Archives, Richmond.

Database entry describing files in a collection, created and offered by an online provider:

Indiana Commission on Public Records, “General Land Office Index,” IN.gov (http://www.in.gov/iara/2592.htm : accessed 5 March 2016), entry for Henry Bickel, T25N, R3E, S20&21; generically citing “land office plat maps and field notes” as the source of the database.

POINTS TO NOTE (Original Documents):

- When using manuscript collections, the U.S. convention has long been this: Cite the document from the smallest element to the largest. The author of the document (or the name of the document or file, if there is no author) is usually the smallest element. The archive and its location is the largest. (Note: In most other Western nations, the pattern is reversed: citations start with the largest element and work down to the smallest.)

- In the digital age—particularly when using a relational database to store our research notes and when using a number of documents from one collection—our data entry is often more efficient if we first identify the online database that delivered the document. Using that as our Source List Entry, we can easily select that source from a pick-list, each time we add a new record from the collection; then our software’s template will automatically generate the rest of the details about the provider. We need only add (a) the specific detail for our item-of-interest, as the last element of Level 1; and (b) the source-of-our-source, as Level 2.

POINTS TO NOTE (Database Entry, Etc.):

- In the State of Indiana database above, the known creator of the database is identified prior to citing the database title—as one would do in citing, say, a book chapter by an individual author before citing the whole book.

- The Indiana database did not provide a specific citation of the source for the Henry Bickel entry. In this case, Layer 2 provides a generic identity of the provider’s source (i.e., our source-of-the-source).

Complex URL Situations

Original document digitized by & accessed through online provider, with

- Citation to website's base URL, when individual documents don't have a stable URL

- Emphasis on creator/author of the original collection

City of St. Louis, Missouri, Circuit Court Case Files, case no. 6, William Clark v. Nicholas Brazeau (Nov. 1809), writ of Copius ad Respondum in Trespass, 24 July 1809; consulted as “St. Louis Circuit Court Historical Records Project,” digital images, Missouri Secretary of State, Missouri Digital Heritage (http://stlcourtrecords.wustl.edu/index.php : accessed 4 September 2014), search term: “Nicholas Brazeau,” image 2 of case file; citing Office of the Circuit Clerk, City of St. Louis.

Original document digitized by & accessed through an online provider, with

- Complicated or multiple URLs

- Emphasis on document

“Muster Roll of the Field Staff and other Commissioned Officers in Colonel Goose Van Schaick’s Battalion of Forces raised in the State of New York and now in the Service of the United States of America, Dated in Barracks, Saratoga, December 17 1776,” for Daniel Budd, Adjutant; consulted as “Revolutionary War Rolls,” database with digital images, Fold3 (http://www.fold3.com : accessed 4 September 2014), images 10188247, 10188258, and 10188267; citing Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775–1783, National Archives micofilm publication M246, roll 77.

Original document, digitized by & accessed through online provider, with

- Citation of "path" via "waypoints"

- Emphasis on creator/author of the collection

- Generic citation to a long-running record series

Madison County, Mississippi, Tax Rolls, 1829–1842, unpaginated entries arranged chronologically, all years read for entries relating to Vick, Green, and Anders; consulted as “Mississippi, State Archives, Various Records, 1820–1951,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/search/collection/1919687 : accessed 4 September 2014), path: Browse > Madison > County tax rolls; citing MDAH boxes 3717 and 3445.

POINTS TO NOTE:

- The St. Louis and Madison County examples emphasize the creator of the collection because many researchers who use government records organize their source lists by the name of the jurisdiction. But ... the muster roll example leads with the document name because it has no known creator or author; this is a common situation with historic documents.

- In the muster roll example, the name of the document is in quotation marks because it is quoted exactly as it appears on the titled document. But ... In the St. Louis and Madison County examples, the ID of the probate file and the tax rolls are not placed in quotation marks, because they are generic identifications; no title is being quoted.

- In the St. Louis example, the URL is the base URL for the project (or collection). There, search-box results link to the file. Because individual images do not have a dedicated and stable URL, Layer 2 includes the search term and identifies the specific image.

- In the Madison County example, the URL is also the base URL for the collection. Layer 2 includes instruction as to how to locate the document at that URL, because the collection is enormous and a specific path must be followed past that URL. The number at the end of the URL is not an image number; it represents the site's cataloging number for the database.

- A generic citation such as Layer 1 in the Madison County example can be used when a large body of records is searched with negative results.

Added Commentaries (Which, Incidentally, Are Not Discursive Notes):

All the above examples focus on the first three layers of a citation, which cover (a) original sources, (b) providers that deliver sources originating elsewhere, and (c) the provider's source-of-the-source information. Many times we need to add a fourth layer: our own analytical remarks about the material we are using. For that layer, we also have choices:

- If it's a short commentary, we might include it as part of the "sentence" that contains the citation. In this case, we would add a semicolon after the source-of-the-source layer and then make our comment before closing out the sentence.

- If it's a longer commentary, especially one that needs multiple sentences for full development or clarity, then it's best to close out the citation sentence with a period and start a new sentence for our commentary.

That said, let's also clarify a frequent confusion: an analytical comment on a source is not the same as a "discursive note." The best definition of "discursive," in the context of reference notes, might be that provided by The Free Dictionary:

discursive ... tending to depart from the main point or cover a wide range of subjects2

Many historical writers do use discursive notes, intermittently with reference notes, to discuss peripheral subjects that "depart from the main point" of the narrative they are writing. That practice allows them to include many random things that are interesting, informative, or related in some way but not directly on topic.

Options—not ‘More Rules to Memorize”

Like most of the 802 pages in Evidence Explained, the examples in this QuickLesson are ‘food for thought.’ They are not rigid rules. They cover a sampling of issues we frequently encounter, and are offered to help you think through what you are using and the manner in which those sources and their quality can be most-clearly identified.

1. Extract: A portion of text quoted verbatim out of a record, usually enclosed in quotation marks. Unlike a transcript, it does not represent the complete record, although it is more precise than an abstract. For distinctions between extracts and abstracts or transcriptions (two other words loosely but often incorrectly used for the census databases), see “QuickLesson 10: Original Records, Image Copies, and Derivatives,” Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-10-original-records-image-copies-and-derivatives ).

2. The Free Dictionary by Farlax (http://www.thefreedictionary.com/discursive : accessed 6 September 2014), for discursive, "Thesaurus" section. EE addresses this subject of discursive notes at 2.7 and in a QuickTips blog posting, "Overlong Citations & Discursive Notes," Evidence Explained: Historical Analysis, Citation & Source Usage (https://www.evidenceexplained.com/quicktips/overlong-citations-discursive-notes : posted 13 July 2014). Examples of discursive notes are shown there.

IMAGE SOURCE: an EE original composite of royalty-free images licensed from CanStockPhoto (www.canstockphoto.com).

POSTED: 4 September 2014

UPDATED: 5 March 2016 and 24 October 2018 to reflect URL changes and database-name changes.